The Pliocene (see Geologic Time Scale, earlier lesson ), from 5 mya to 1.8 mya, was a time of climatic change, which altered the face of Africa as well as much of the rest of the world. It is unlikely to be a coincidence that this is the same time period when hominins, bipeds, evolved from ape-like ancestors and spread into Asia and Europe.

The earlier Miocene Epoch (23-5 mya) was, if you remember, a time of hominoid radiation. More hominoid species evolved during the Miocene than ever existed before or since, and probably included some early experiments in bipedalism. The Miocene was a relatively warm and wet Epoch, although toward the end world-wide climate began to cool, and on most continents the first grassland or savanna areas began to appear. These offered new habitats to all animal species, and the ancestors of most modern hoofed animals, as well as their predators, also appeared.

The ancestors of Ardipithecus and probably other early hominins also evolved as the Miocene turned into the cooler, drier Pliocene. "Cooler" in comparison to the Miocene, but the Pliocene was actually for the most part warmer than today. As India continued to crunch into the rest of Asia, the Himalayan Mountains developed, and there were major tectonic events on all continents which created new and changing ecological niches for evolution. The Mediterranean Sea essentially disappeared, and grasslands spread at the expense of forests.

As the Pliocene became the Miocene 5-6 mya, the vast grasslands which were to cover almost all of eastern Africa began to develop. As new habitats came into existence, various species from different mammalian groups began to adapt to the new environment. Among those adapting were perhaps several groups of hominoids who were already developing into hominins. While the first hominins developed some bipedal traits while living in the forests, later hominins evolved as adept bipeds while exploiting the forest edge, more open woodlands, and finally the grasslands. At this time, it is difficult to say which hominin fossils were at least partially successful, and continued to evolve, and which ones turned out to be short-lived evolutionary failures. A selection for bipedalism (as well as a few other hominin traits) had occurred, and these species are generally classified as the first hominins.

The earliest possible hominins described in the text (thefragmentary Sahelanthropus and Orrorin) may have evolved in response to this changing environment; the result of this climatic change appears to have been a small hominin adaptive radiation, with more hominin (bipedal) species than there would ever be again. The earliest definite hominins (starting with Ardipithecus, see below ) were as often found in forest or open woodland habitats as grasslands. Though bipedal, they retained relatively long arms, curved fingers, and perhaps a divergent big toe, so that they could also easily climb trees. They may well have been exploiting more than one specific habitat, which is what their physical traits suggest. An increasing reliance on tool use may have contributed to a selection for smaller front teeth, and a possibly related slight expansion of their brain. In a time of changing environments, flexibility, and the ability to learn, may have been the trait selected by natural selection.

The earliest definite hominin or bipedal species known is Ardipithecus ramidus, at about 4.4 mya. (The text discusses this fossil, but its information is a bit out of date. Also, on the table on page 43, it refers to Ardipithecus as Australopithecus ramidus; this is an error.) Excavated in Ethiopia between 1992-1997, the fossil has long been thought to be a biped based on the position of the foramen magnum. The long-awaited release in Fall 2009 of the analysis of the skeletal remains strengthens the case that Ardipithecus is most likely a biped, and a possible ancestor of the Australopithecines, and therefore of modern humans. Some 125 bits and pieces of perhaps 36 individuals have now been analyzed. Included in the bones is a complete hand, almost all of the foot, much of the skull and teeth, much of the pelvis, as well as other portions of the skeleton.

Small, with a small ape-sized brain, Ardipithecus has a very human-like hand, with a short thumb, but relatively long fingers. A flexible wrist meant he would not have been a great brachiator, probably not much better than modern humans. His feet have the divergent and relatively short big toe of apes, rather than the long big toe of modern humans that is aligned with the other toes. The pelvis appears to have a shallow sciatic notch, and certainly a broad and thick ilium, again indicating his bipedal ability. The lower part of the pelvis appears to more resemble the apes, which would indicate that as a biped he would not have been particularly agile. He appears by his skeleton to have been a better tree-climber, but less adapted to bipedalism, than we are. He is curently found only in a wooded environment, but has already made many of the changes toward bipedalism.

Skeleton of Ardipithecus, showing his hominin pelvis, and diverent big toe

Ardipithecus teeth already show the flat, non-projecting canines of the Australopithecines. Since the large canines of male chimps and gorillas are primarily used for status competition between males, one interpretation is that males were already finding that cooperative behavior helped survival. According to reports, there was little sexual dimorphism in teeth, and also relatively little sexual dimorphism in body size. Probably omnivorous in terms of diet, this early hominin appears to have lived in a moist, open woodland environment. He is currently the most likely ancestor of the Australopithecines, a position that could easily change with more evidence.

For a somewhat "media-hype" article, the link to National Geographic news does offer good information, and is recommended. You should also listen to two required presentations from You Tube: The Analysis of Ardipithecus ramidus (10 minutes), and the second on Building Ardi's World (about 4 minutes.) (If either doesn't link directly, type in the title on You Tube search.) Remember, despite the You Tube hype of Ardi's discoverers, paleoanthropology has never been looking for a "missing link" half-way between ourselves and chimps, because we did not evolve from chimps, and neither science nor Darwain ever said we did. Chimps, bonobos and ourselves had common ancestors that we now know lived around 6 million years ago. Ardipithecus indicates again the importance of the evolution of bipedalism, and of hominin dentition, in our very earliest ancestry. The "missing link" has always been a myth; however clearly there are many hominins with "mixed" ape-like and human-like traits, as well as unique traits, not just Ardipithecus. These are indeed transitional forms between the common ancestors of apes and humans, and ourselves. And given the "bushiness" of our evolutionary tree, some are definitely not our ancestors. Ardipithecus however is currently a likely ancestor of the next major early hominin group, the Australopithecines.

Of the earliest hominin or possible hominin fossils, the most likely ancestor is one of the many Australopithecine species, Australopithecus afarensis. Fully bipedal, though with the longer arms and fingers of most of the early bipeds, this fossil appears as early as 4 mya, and lasted until 3 mya. Found at several sites in east Africa, Au. afarensis has many dental traits that indicate a more human dentition, but has a very small cranial capacity of between 400 - 500 cubic centimeters; this puts him squarely within the range of modern chimps and bonobos in terms of brain size.

Au. afarensis

There is very little evidence of the cultural capabilities of Au. afarensis. No stone tools have been found this early, and if he included a larger percentage of meat in his diet than do modern chimps, it was probably more as a scavenger than a hunter. However, see the paragraph in next section below for a recent discovery of possible tool use by Au. afarensis.

As many as ten different Australopithecine species may have existed in Africa in the period between 4 mya-2 mya, plus perhaps three species of a related biped, members of the genus Paranthropus. For some idea of the "bushiness" of early hominin evolution, spend a little time on the lesson entitled "Phylogeny", which includes all hominins and possible hominins from 6 mya to the present. Most of these early hominins were not our ancestors; Au. afarensis may have been our ancestor, based on his very early date, and his generalized traits.

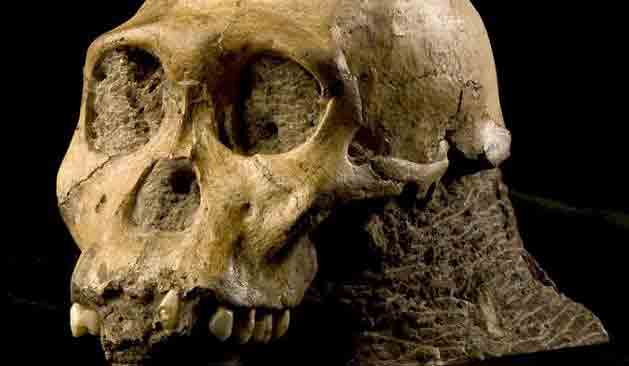

The most recent Australopithecine discovered is Australopithecus sediba, whose discovery in South Africa has received considerable media attention since it was announced in April 2010. A very complete skull of an 8-12 year old boy was discovered in a sinkhole-type cave, along with that of a female in her 30's. Fully bipedal, the two fossils have relatively long arms and fingers compared to the length of their legs, and several traits that have led some paleoanthropologists to suggest Au. sediba might be an early member of the genus Homo. The cranial capacity however is very small, at around 420 c.c., and the earliest fossils of the genus Homo are older than Au. sediba, who is dated at between 1.78-1.95 mya. As is the case with all these early fossil species (including the early members of the genus Homo, see below) it is difficult to say exactly how Au. sediba is related to other Australopithecines or to our Genus. He is more evidence that small bained bipeds, perhaps multiple species, were common in Africa in the late Pliocene/early Pleistocene.

The beautifully preserved skull of Au.sediba

[The Phylogeny contains considerably more information, and more hominin or possible hominin species, than you need for this class.]

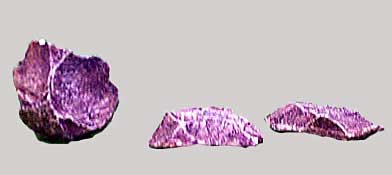

Many of these Australopithecines may have used and even made wooden tools, as do modern chimps. Nothing of this is preserved in the fossil record. However, very early stone tools have long been found at sites in Africa. Long before Louis Leakey discovered any fossils at Olduvai Gorge, simple stone tools were found there. Similar tools were also found at sites in South Africa, Ethiopia, and Kenya. These tools, called Oldowan tools, are characterized by a core (often a water-worn pebble) from which one or more flakes have been removed. In the past, it was thought that the core was the only tool; more extensive analysis has revealed that the flakes were often heavily used and may have been the main purpose of the activity.

Three Oldowan Tools: A core (left) and two flakes

Oldowan tools may have had many uses, since all the more recent early hominins clearly lacked large incisor and canine teeth. The most obvious task for the tools was in cutting meat off bones. The site with the oldest tools, Gona River in Ethiopia, is dated at 2.6 mya. The site of Bouri, also in Ethiopia, has a few similar stone tools plus several animal bones with cut marks as well as some that appear to have been smashed with a stone tool. Bouri is also the site where Au. garhi was discovered. Au. garhi may well have been a tool maker, but it is important to realize that Oldowan tools have been found at the same sites as almost every single hominin that is 2.5 million years old or younger. That means stone tools have been found with Au.africanus, Paranthropus and various contemporary early Homo remains. It's hard to say if only one species made the tools. In any case, presumably stone tools indicate more of a dependence upon learning to survive, and larger brains were advantageous. This selection resulted in the earliest members of our genus.

Using naturally sharp bits of stone for cutting up animals may be even older. In Aug. 2010, Science published a report of cut marks found on bone dating from around 3.4 mya. The only known hominin around at the time was Australopithecus afarensis. The stone tools used, or possibly made, by Au. afarensis have not been found, and some paleoanthropologists think is is unlikely that the cut marks are really cut marks. (Remember however, teeth marks and cut marks on bone are very different under the microscope.) In any case, the evidence may indicate that Au. afarensis was able to use stone as tools to aid in butchering larger animals; the animals themselves may have been the prey of carnivors whose kills were being scavanged. For photo and more information, click here.

Archaeologists often use the appearance of stone tools as the first evidence of the human cultural adaptation. These earliest cultures are often referred to as Paleolithic. The Paleolithic starts at 2.5 mya (during the Pliocene), and lasts until the end of the Pleistocene at 12,000 ya. During this time hominins developed a variety of flaked stone tool traditions, of which Oldowan is the oldest; hominins also developed many other cultural capabilities, including fire, dwellings, burial, bodily decoration and art, and no doubt complex religious and social belief systems.

WARNING: Your text presents the subsequent development of human evolution as essentially consisting of two fossil species of the genus Homo leading up to our own species, Homo sapiens. The two species discussed in the text are listed as Homo habilis and Homo erectus. Unfortunately, the text is presenting a simplistic viewpoint, and one largely unacceptable to the majority of paleoanthropologists today. In fact, neither H. habilis or H.erectus (particularly H. erectus from eastern Asia) are considered to be ancestors today. Therefore, use caution and rely on the lessons for complete information!!

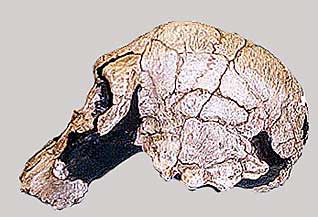

Currently, the earliest of the early members of our genus is classified as Homo rudolfensis. [Please note that your text groups H.rudolfensis with somewhat later members of the genus as Homo habilis. Check out the Phylogeny; H.habilis is probably not an ancestor.] H.rudolfensis is the first hominin with a cranial capacity over 600 c.c. ( 600-800 c.c., still far from the modern average of 1400 c.c.). H.rudolfensis dates from 2.4 to perhaps1.6 mya, and has been found at sites in Kenya, Ethiopia, and Malawi, sometimes associated with Oldowan tools. While as the Phylogeny shows, H.rudolfensis had several hominin contemporaries, it is possible that his dependence on culture led to a relatively rapid selection for larger brains, so that his descendant Homo ergaster was in many ways very modern looking. H.ergaster dates from about 1.9 or even 2.0 to perhaps 1.2 mya, and had a cranial capacity of that ranged from 750-1250 c.c. This range for modern humans is from 900-2000 c.c., so H. ergaster is the earliest hominin to be within the range of modern cranial capacity. [Note: Some paleoanthropologists still classify both these fossils as early Homo erectus.]

H.rudolfensis (left) and H.ergaster

Homo ergaster is best known by a remarkable find of a juvenile skeleton (whose skull is shown above) that is the most complete (106 bones) pre-Neandertal fossil ever discovered. This is the Narikotome boy (or Turkana boy) from Kenya. Details of the pelvis indicated his sex, and the fact that many of the ends of the long bones were not fused to the shafts of the bones indicated he was between 9 and 12 years old when he died. (To see an enlarged view of his skeleton, click here. To see a reconstruction of what he may have looked like, and a short video on how these reconstructions are done, click here, then click on "Launch Interactive" to view the 5 minute video.) The boy was tall (already over 5'4"), narrow hipped, and long legged. He was thin (perhaps no more than 70 lbs or so), and many paleoanthropologists have noted that his post-cranial skeleton looks remarkably like modern boys of his age living in the vicinity.

According to some paleoanthropologists, it is probable that the boy, and the rest of his group, were already adapted to spending long hours hunting and gathering on the African savanna. The main problem to the new life style would be overheating. To facilitate heat loss, there would be a selection for sweat glands (which humans, unlike apes, have in abundance) and for relative hairlessness. It is also assumed that he had dark skin and hair on his head to protect against the sun's rays.

The boy also had very narrow thoracic vertebra, some say too narrow to accommodate the nerves necessary to carefully control breathing. Since fine control of breathing is necessary for speech, presumably Homo ergaster could not communicate like moderns. (That doesn't mean that verbal communication would be impossible, only that language as we know it could not be as developed.)

Another interesting fossil is the partial skull and skeleton of a female, also found in Kenya. Paleopathologists have diagnosed her as suffering from hypervitaminosis A, or vitamin A poisoning. Amongst other symptoms, advanced vitamin A poisoning causes lumps of patchy bony growth to accumulate on the bones. The cause may have been consumption of too much liver: liver is a highly favored organ by more recent human hunters, and the fact that someone could "overdose" on it is strong support for a foraging life style. Paleopathologists have also concluded that for many months before she died, this woman would have been seriously incapacitated, and unable to care for herself. Presumably her group cared for her--perhaps providing her with her favorite food: liver!

Stone tools are found at the early H.ergaster sites, but until 1.5 mya they continue to be the same type of Oldowan tool that has already been made for a million years. There are however, sites where animals appear to have been butchered (cut marks on the bones, evidence of smashing to extract marrow, etc.) It seems more likely that many of these animals were being hunted, instead of merely scavenged. There is no convincing evidence that H.ergaster utilized a home base to which they returned each day, though some sites do appear to have been used more than once. There is some evidence that he may have had fire. Eventually, by about 1.5 mya, H.ergaster is associated with a more sophisticated tool type, the Achuelean handax tradition. Many of the sites, not surprisingly, are along rivers and lakes. Mobility and learning seem to have been the key to their survival. (Be sure to read the text for more information on Achuelean handaxes, which is referred to as the "swiss army knife" of the Lower Paleolithic.)

And Homo ergaster was enormously mobile! The evidence now seems to indicate that it may have been H.ergaster who was the first hominin out of Africa. Evolving there perhaps as early as 2 mya, there is a possibility that the fragmentary remains from Longgupo Cave in southern China are H.ergaster. (The teeth of these early Asian hominins resemble H.ergaster more than they do that of Homo erectus.) If so, these hominins reached eastern Asia some 100,000 or so years after they evolved in Africa. More reliably, H.ergaster (or possibly his descendant H.erectus) has been found at the site of Dmanisi in Georgia at 1.8 mya (and called by many a new species, Homo georgicus), and H.erectus has been found near Sangiran, Java at 1.8 and 1.7 mya. This may seem like very little time to go from Africa to Java, but estimates are that a rate of travel of ten miles per generation could have gotten humans to Java in 25,000 years.

Until the early 1990's, it was generally believed that hominins did not leave Africa until approximately one million years ago. The earliest known Asian hominins, Homo erectus from Java and Zhoukoudian in China, were believed to be relatively young, certainly no older than a half million years. None of the sites had been dated with a radiometric dating method, and there seemed no reason to believe that early bipeds were "smart enough" to exploit a vast new continent prior to a million years ago. All that has changed.