The early horticultural societies of the world will be explored in the next unit. For many cultures, farming was the solution to the threat to standard of living posed by rising population levels and changing environments at the end of the Pleistocene. Horticulture was developed independently in southwest and southeast Asia, in northern China, in Mexico, in Columbia/Peru, and possibly in other areas. During the archaeological stage sometimes called the Neolithic, horticulturists expanded from these centers into many other parts of the world. This development and expansion will be explored in the next unit.

Common characteristics of the horticultural mode of production include the following:

1. Horticulture is characterized by a dependency on domesticated plants. Domesticated animals were frequently present also, though not in all environments. Horticultural societies usually lacked the energy investment in irrigation, or drainage systems present in subsequent adaptations. Domesticated animals, if present, usually did not assist in farming, and did not pull plows. A simple hoe or digging stick, easily manufactured by individual family groups, was the primary agricultural tool; the metal plow is conspicuously absent. Horticulture in fact is sometimes known as non-plow agriculture.

Typical horticultural societies practiced either swidden (slash and burn) and/or mixed farming to avoid soil depletion. Irrigation and/or drainage systems were limited. Horticultural societies were well-adapted to, and persisted in, the poor soils of the tropical rain forests and in other areas unsuitable to continuous intensive agriculture.

2. Horticultural necessitated a more sedentary lifestyle, and included:

3. Horticulturists worked longer and harder than foragers, both in terms of average hours per week, and though a lifetime.

4. Like most foraging societies, horticulturalists had a sex division of labor, usually with more rigid divisions than foragers. (The text notes some archaeological evidence of this.) There were often at least part-time craft, religious, and other specialists.

5. Population and health

6. With their larger populations, horticulture societies were socially more complex. Politically most were organized into either tribes, associated with big men, or chiefdoms, associated with chiefs. Political organization will be discussed in some detail in the next unit. While a few foraging societies were able to be sedentary enough and large enough to have these types of political organization, they were generally traits of horticulturalists.

Many of the traits listed for horticulture can be found archaeologically, including the larger villages, more permanent houses, and more and specialized artifacts. As noted earlier and in the text, there is also ample evidence of domesticated plants and animals from many of the sites. Below are just a few examples of the archaeological evidence.

Houses

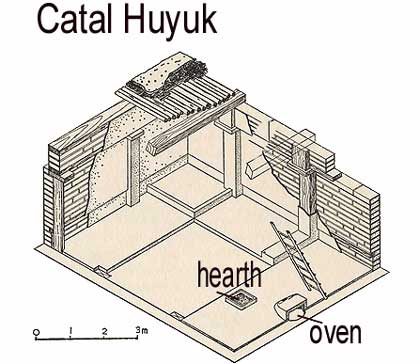

The Neolithic village of Catal Huyuk, in modern Turkey, was occupied from about 6500-5700 B.C. During that time, people regularly renovated dwellings, or leveled some and built others on top. By the time Catal Huyuk was abandoned, the village was on top of a mound of cultural debris (huyuk or hoyuk means mound). The houses themselves were one story, single-room dwellings which usually shared walls with neighboring houses, and meant that access was frequently by a ladder. The houses were made of mud brick, with a wooden support for the roofs. The roof was made of a layer of reeds covered by a layer of thick mud. These houses were considerably more permanent than anything constructed by foragers. This site will be discussed in more depth in the text in the next unit.

House from Catal Huyuk, from Catal Huyuk: A Neolithic Town in Anatolia, by James Mellaart

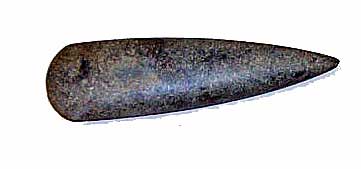

Ground and Polished Stone Tools

While flaked stone tools as well as bone tools continued into the Neolithic, a new method of stone manufacture makes it appearance (hence the term Neolithic, or literally "new stone"). In this method of tool manufacture, a stone would be roughly shaped into the desired shape by "pecking" or hitting it with another stone to remove very small bits. Again using other stones, the tool was then "ground" into the specific shape, say an axhead with sharp edges, and then perhaps "polished" to a high degree of luster. If the technique used was flaking, only rocks with a glassy structure such as flint or obsidian could be used to make tools. Grinding and polishing could successfully turn most rocks into a tool. (Ground stone tools have been found in small numbers in foraging, Mesolithic sites also, but it is still considered a hallmark of the Neolithic.)

Ground and Polished Ax Head (with grooves for hafting)[left] and a Celt (probably ceremonial)

Pottery

While ceramic (fired clay) figurines are known from the Paleolithic, in the Neolithic people started to make various kinds of ceramic containers, or pottery. Since farmers tended to stay in one place for long periods of time, pottery was now practical, and pottery artifacts are one of the characteristics of almost all Neolithic sites. Besides being useful for containers, pottery proved to be an attractive art form, as can be seen below. The earliest pottery has been found in Japan at Jomon sites, probably as early as 12,000 ya, and became increasingly common at those sites in the late Mesolithic/early Neolithic.

Incised "Comb-Pattern" Vessel from Korea (Neolithic ca 4000 BC) [from www.metmuseum.org]

The next unit will focus on these early horticultural societies, and the spread of horticulture as an adaptive strategy. We often think of many of the traits listed above as "progress". I have already given you a few reasons to question this; read Diamond's article (next lesson) for more reasons.