According to the replacement hypothesis, Homo sapiens evolved perhaps as early as 200,000-250,000 years ago, in Africa, from an earlier Homo population, perhaps Homo heidelbergensis. [Note: there are no subspecies within our species; your text's terminology is incorrect.] Moving out of Africa around 100,000 years ago, modern humans quickly expanded into Asia and Europe, replacing the existing populations of Homo erectus (and Homo floresiensis if that is a valid species) and Homo neanderthalensis. By 40,000-60,000 years ago, this new species had occupied Australia and shortly thereafter the Americas, as noted in the text. By 13,000 years ago, H. sapiens was the only hominin species in existence. By the end of the Pleistocene (and the Upper Paleolithic) at 12,000 years ago, only Iceland and most of the Pacific Islands had yet to experience humans.

A 20,000 year old Homo sapiens

The evidence supporting the replacement hypothesis can be divided into three types: the mtDNA evidence, the fossil evidence and the cultural evidence. Fossil and cultural evidence will be discussed briefly in this lesson, and the mtDNA evidence in the next lesson.

Some of the physical traits that characterize Homo sapiens include

• a well-developed chin

• the presence of canine fossa (the depressions in the face near the roots of the canine teeth);

• a somewhat higher brain case and thin cranial bones;

• smaller face and eye sockets;

• and a sharply curved or flexed cranial base

At least some of these traits can be seen above. Since the cranial base forms the roof of the larynx, the curvature indicates a physical ability for fully modern language. In addition, the text notes the development of full cognitive fluidity, a trait for which there is no specific physical evidence, but which is inferred from cultural evidence and the relatively rapid spread of Homo sapiens over most of the earth.

Except for the Eurasian Neandertals, the period from 250,000 to 40,000 years ago is poorly known elsewhere both in terms of paleoanthropology and of archaeology. Yet the physical evidence that does exist provides support for saying that the really important (from our perspective) evolutionary events during this time period, were taking place once again in Africa. While sites are few and often poorly dated, and fossils are usually fragmentary, the oldest Homo sapiens are clearly in Africa. These include:

Presumably, modern traits evolved in a small population of early Homo heidelbergensis (if that is the most immediate ancestor) and proved to be adaptive. These traits enable Homo sapiens to spread throughout Africa at the expense of other existing hominin populations. Very shortly, Homo sapiens left Africa, as at the sites of Tabun and Qafzeh in Israel he is found associated with a Mousterian tool tradition, and a date of 90,000 years ago. There are Neandertal sites in the region that date back to 200,000 years ago, and Neandertals persisted in the area until 40-45,000 years ago. There appears to be a period of some 50,000 years of coexistence between anatomically modern humans and the Neandertals, although there is no archaeological evidence as to the nature of that coexistence.

In Europe, the best known area, a sharp cultural change has long been associated with the appearance of anatomically modern humans at about 40,000 years ago. (This is referred to culturally as the Upper Paleolithic, and is associated with Homo sapiens.) The sharp cultural as well as physical change lead to the assumption that it was the superiority of their culture that allowed Homo sapiens to in some way cause the extinction of the Neandertals. While that may be true in ways that are unclear archaeologically, the African sites seem to indicate that humans became anatomically modern throughout Africa before they are consistently associated with certain cultural artifacts. Still, these artifacts are found, and at extremely old dates, in Africa. Cultural innovations traditionally associated with Homo sapiens in Europe that in fact are first found in Africa include:

All dates indicate the earliest dates available, and all are in Africa. Thus evidence of a more modern culture appears earliest in Africa, but older cultural traditions persist even as modern humans become the only hominin. An already mentioned example: as Homo sapiens migrated into Southwest Asia, their culture remained indistinguishable from the Mousterian culture of the existing Neandertals. Presumably innovations from Africa (such as blade manufacture and bone tool manufacture) subsequently diffused into southwest Asia and Europe, perhaps carried by more immigrants.

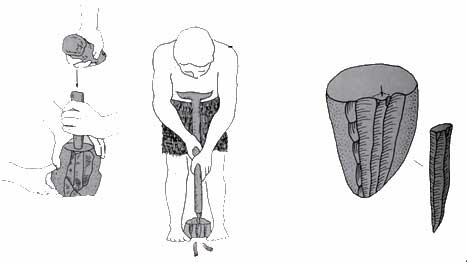

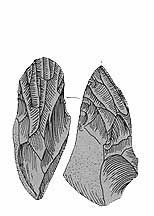

Homo sapiens entered Europe at least by 40,000 years ago, from around the eastern coast of the Mediterranean via sites like Qafeh, and also from North Africa into Spain. They brought with them the distinct Upper Paleolithic culture known as the Auragnacian, based upon blade tool manufacture and an extensive series of symbolic or ceremonial artifacts. This was the first of the so-called Upper Paleolithic cultures of Europe. Decorated artifacts, animal and human figurines, and the cave paintings are all associated with early H. sapiens in Europe. Below is a drawing of blade making and below it, drawings of some of the artifacts from blades. Be sure to review the text for further information on the European Upper Paleolithic, as well as non-European sites from this time-period.

Blade Manufacture (From Fagan: People of the Earth 6th Edition)

Three Tools Made From Blades: From left, a burin (used to carve bone); a scrapper (top and side views) and a point. (From: Fagan People of the Earth 6th Edition)

On the left are examples of bone harpoons; on the right, a hafted harpoon and left, a spear thrower, or atlatl. (From Fagan: People of the Earth 6th Edition)

While possible evidence of some attempt a bodily decoration (a most human trait!) is found associated with the Neandertals, there is ample evidence associated with early H. sapiens The include carved pendants (of bone and ivory), necklaces of animal teeth and bone, and other decorations of shell. In much of Europe and into central Asia, early H. sapiens is associated with carved figurines, primarily of humans and primarily of females in a style known as Venus figurines. Below is the Venus figurine used to decorate all the Unit 1 lessons: six inches high, she was carved in ivory, and is shown here backed by an obsidian flake. Venus figurines typically have large breasts and stomachs, and are often interpreted as pregnant women, though the exact meaning and function in Upper Paleolithic culture is unknown. These are examples of Upper Paleolithic portable art.

A Venus Figurine

Early Homo sapiens in Europe is especially noted for cave art, more properly referred to as mural art. You are required to visit two sites and examine the art. First, and oldest, is Grotte de Chauvet in France. Once into the site, be sure to read the section "Time and Space", but also click on Visit, and view the cave (the visit itself takes a lot of clicking, but it is worth it. Be sure to do the extra clicks to enlarge the paintings.) Also required is the Virtual Visit of one of the most famous as well as fabulous of the cave painting sites, Lascaux. also located in France. (Be sure you take the Virtual Visit of the cave, but there is lots more information at this site; you are required again to read the "Time and Space" section; click on "Discover" to get there.) [Note: Lab 2 is on these two sites. Your text of course also provides additional information on Lascaux; be sure to read it as well as doing the virtual visit of Lascaux for the lab.]

What happened to Neandertals when faced with this invasion at the height of the last glacial episode of the Pleistocene? Did they adopt some of the cultural innovations of the invaders? Did they under any circumstances interbreed with the invaders? Both of these have happened time and time again between groups of Homo sapiens, both historically and prehistorically. It should have happened with the Neandertals if the two groups were the same species, and must have happened if the multiregional hypothesis (or regional continuity model) is to have any credibility. The youngest Neandertal fossil in Europe dates at possibly 28,000 years ago, though almost no Neandertals are found more recently than some 39,000 ya.

There is some evidence of possible cultural diffusion. A brief cultural development called the Chatelperronian appears about 35,000 years ago in parts of France, Italy, and Hungary. This "culture" appears to combine some of the blade manufacturing industry with traits of the Mousterian tool tradition, and there is considerable evidence of bone tool manufacture. In addition, there are associated carved and incised artifacts, including a carefully carved bone pendant that was either made by a Neandertal, or acquired by one from modern humans. At two of the sites in France, Chatelperronian and Auragnacian deposits are interlayered, indicating repeated use of the same site by the two groups. Most archaeologists now consider Chatelperronian to represent the influence of modern humans on the Neandertals, and that Chatelperronian is a Neandertal development, though a general absence of fossils makes this interpretation far from proven.

As to interbreeding, there is little or no reliable evidence, depending on whose interpretation you want to believe. (Since what a person "wants" to believe has no place in science, it is better to say that the evidence is at the moment inconclusive!) The best claim to interbreeding is a recent site at Lagar Velho in Portugal, where a 24,500 year old skeleton of a four year old child combines Neandertal and modern features. Since this is almost 4,000 years after the presumed demise of Neandertal, the discoverers claim that the child is the product of a population formed by generations of interbreeding, and not a "one time" mating between the two species. If the discoverers are correct in their interpretation, then the Neandertals could, and in at least in some places did, exchange genes with the invading modern human populations. (Others say the child is a particularly husky example of H. sapiens. To read some of this rather heated debate, if interested, click here.)

If Europe, with its large numbers of Neandertal and Homo sapiens fossils, and its numerous archaeological sites, can not clearly prove one hypothesis (Replacement or Multiregionalism) is correct, Asia, which is largely unknown from this time period, can add little. Other than the Israel sites already mentioned, and a few others in extreme southwest Asia, there are few archaeological sites, and even fewer fossils. There is an anatomically modern individual from Niah Cave in Borneo reliably dated at 41,500 years ago. In addition, there are several sites in China that are somewhat younger, and a series of modern Homo sapiens skulls from Zhoukoudian from layers dating between 18,000 and 10,000 years ago. In 2002 it was announced that a Homo sapiens skull from Liujiang in Southern China has been tentatively dated to 139,000-111,000 years ago and that Homo sapiens teeth from nearby sites have been dated to around 90,000 ya. Given the 195,000 ya date for H. sapiens in Ethiopia, these dates from China, even if valid, do not resolve the issue. (That is to say, H. sapiens could still have migrated into China, out of Africa.)

Unfortunately much of the area is still poorly explored in terms of archaeological and paleoanthropological sites. The early dates for H. sapiens in eastern Asia, connected with the late date of 27,000 ya for Homo erectus in Java does not prove either a replacement or a partial multiregional model, though the fact that H. sapiens and H. erectus may have been so long contemporaries in east Asia does seem to make the replacement model more convincing, to me at least. H floresiensis on available evidence would appear to have been replaced by H. sapiens, but it could be argued that this is an isolated phenomenon. You might want to check on the state of the evidence in another ten years!

The oldest skeletal material in Australia is a Homo sapiens from the Mungo site, now reliably dated at about 42,000 years old. (It is also in Australia where some think that Homo erectus made his "last stand": the 19,000-22,000 ya fossils from Kow Swamp. However, some think that this new and older date for Kow Swamp indicates a local evolutionary trend toward robustness.)

The date for the population of the Americas is highly controversial, as is the method used to get there. There is increasing evidence of occupation sometime between 20-40,000 years ago (ya) or even earlier, by, of course, Homo sapiens. One of the earliest generally accepted sites is Monte Verde, close to the coast in Chile. Dated at 14,500 ya, the site indicates that people probably moved along the coast from east Asia and over and down the coast of North America--probably with the aid of some form of boats--during the last glacial period of the Pleistocene. Ocean levels were much lower, and most sites would have been buried by rising seas. In fact, Monte Verde has lead some archaeologists to hypothesize a "Kelp Highway" that was followed along the western coast of the Americas, since a variety of edible seaweeds have been found at Monte Verde. In addition to 42 different species of plants have been found ( including wild potatoes, mushrooms, berries and other fruits). The most common animal hunted at Monte Verde was the now extinct mastodon. (Click for picture)

A new, and not generally accepted North American site is that of the Topper site in South Carolina. Underlying a well established Clovis site at about 13,000 ya, a pre-Clovis site underlying it has recently been dated at around 50,000 ya. If the dating proves valid, this would indicate a very early occupation of the Americas. (Click here for more information on Topper.) A better site has recently been unearthed in Texas. Dated at some 15,500 ya, hundreds of flakes, other flaking debris and some 50 well-formed artifacts have been discovered, leading some to call it the best pre-Clovis site in North America, and proof that Clovis was an indigenous North American development. (Click here for more information.) [Be sure to see the text for more information on early sites in the Americas--including Lindenmeier--and in Australia.)