In all probability, the eastern half of what is now the United States was also a secondary center of horticulture for four crops that ultimately had limited impact. These four plants were being gathered by foragers at least as early as 6,000 BC in the eastern US. During the time between 2,400 - 1,400 BC, the four plants were domesticated in the eastern US and began to supplement people's diets before the introduction of maize into the area. Two of these plants are currently classified as weeds: the marshelder , and lambs quarter or goosefoot (still sometimes eaten as a green.) One of the five species of squash that were domesticated in the Americas appears to have been first domesticated, or at least independently domesticated, in the eastern US, Cucurbita pepo ovifera, which includes the acorn squash. The final plant was the sunflower, which may have been independently domesticated in both Mexico and eastern US. (Click here to read article on evidence of early eastern US domesticates; not required. However, pp. 258-259 in text, and all of Chapt. 6, are required) These plants eventually enabled Native Americans in the eastern US to develop farming villages that were of course still dependent upon hunting for meat. (Remember the lack of domesticable animals in the Americas discussed at the start of Unit 2.) For the most part, these early farmers lived along the rivers and lakes of what was still a heavily forested eastern US. Two distinct cultures arose centered on the Ohio River valley, one following the other in the same area. These are known as Adena and Hopewell, which will essentially be discussed here as one continuous cultural tradition. Politically, both at their height were probably composed of small chiefdoms that shared religious and ceremonial beliefs, were trading partners, and probably shared many other aspects of culture.

Adena culture was the earliest of the mound building cultures of eastern North America, beginning around 1000 BC and lasting until close to 200 BC or longer. Adena refers to what were probably related groups, possibly small chiefdoms, who shared a burial, ceremonial, and trade system. The cultural tradition known as Hopewell followed, continuing and developing the burial and ceremonial system, which in some areas continued until close to 800 AD, though many original Hopewell sites were abandoned by 400 AD.

Map Showing the Main Area of Adena-Hopewell, and the Extent of Hopewell Sites (from Price and Feinman, Images of the Past, 1993, p.252)

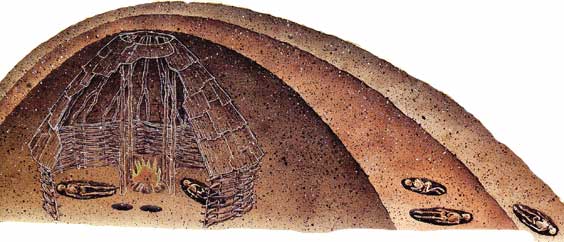

The Adena people practiced horticulture, made pottery, and developed funeral practices which involved burying their dead in earthen mounds, often with elaborate burial goods. Although dead were sometimes cremated, or exposed until the bones could be collected, most were buried in log tombs, over which a circular house was built, presumably as part of a burial ritual that took several days. Then the house was burned or pulled down, and a mound built over it. The sketch below demonstrates the process, and also shows how mounds were often subsequently used to bury others, which resulted in large mounds of several layers with burials of different ages. Adena mounds were as much as 300 feet in diameter, and over 60 feet, high, made by hundreds of people carrying baskets of selected earth, often from different ares. The result is sometimes a multicolored mound when excavated, with discrete basketloads clearly visible.

Sketch of an Adena Mound (from Lost Civilizations: Mound Builders & Cliff Dwellers, Time-Life 1992, p.37)

Most burials included some grave goods, and in some cases the central body was accompanied by elaborate offerings. The even more elaborate tradition called Hopewell grew out of the early Adena, replacing it and expanding its influence after 200 BC. Hopewell was probably also a series of chiefdoms that followed much the same burial practices and had much the same religious beliefs, and who were the center of trade networks that imported obsidian from the Rocky Mountains in the west, copper from the Great Lakes region, mica from the Carolinas, and shells from the Gulf of Mexico. Many of these were formed into elaborate items depicting the status of the owner, and were found both with the burials of high status individuals, and within the villages themselves. A few examples are provided below.

A Red Horse Sucker Fish, Made of Hammered Copper (from Lost Civilizations, p.30)

Freshwater Pearls, found by the Hundreds in Hopewell Burials (from Lost Civilizations, p.30)

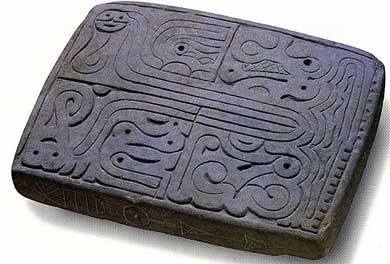

A 4" by 5" Adena stone, possibly used as a guide for tattooing. The reverse side is grooved like a whetstone indicating that bone needles were sharpened on it. (from Lost Civilizations, p.24)

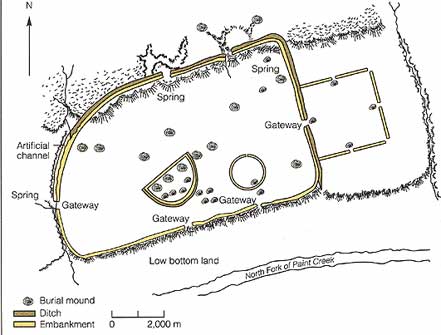

Many of the villages of the Hopewell appear to have been fortified, and were often on natural hilltops. This strengthens the interpretation that various small and competitive chiefdoms were occupying the area, with a relatively dense population that was based on the cultivation of the crops listed above, along with extensive hunting, fishing, and gathering.

Plan of the site of Hopewell, Ohio (from Price and Feinman, p.251)

Adena-Hopewell people were also smokers, and of course lived in the homeland of tobacco, which was probably grown as a domesticate very early. Historically, some 27 different plant species were smoked by Native Americans, and the earliest pipes are found in eastern US dating at 2,500 BC. Pipes are found by the hundreds in sites, including graves, and were often animal effigies, as below. These pipes were also important trade items.

Carved Stone Pipe, featuring a roseate spoonbill perched on a fish. The bowl of the pipe is on the back of the bird. See p. 279 in text for another example. (From Lost Civilizations, p. 65)

Some time after 400 AD, the elaborate trade network of Hopewell began to fall apart, though the reasons are unclear. Certainly at about this time slash and burn horticulturalists dependent upon maize began to appear in the river valleys, and increasing competition for land along with rising populations may have broken the trade network, and ultimately led to the Hopewell decline. (See text pp.276-280 for moe pictures/information on the Hopewell.}

The spread of maize horticulture appeared to have also involved the movement of people, with different symbols and different religious beliefs, as well as better weapons of warfare, the bow and arrow. Along with maize, these people grew beans and squash, and the sequence of chiefdoms that they influenced have become known as the Mississippian, subject of the next lesson.