The change in the Mississippi River valley to maize, bean, and squash cultivation indicates that these southern Mexican domesticates had reached far to the north, and much about the Mississippian tradition indicates influence from the south. It is probable that there was at least some migration from and trade with the large agrarian states that had developed in MesoAmerica (more on those in the last unit.) Generally however, the new tradition appears to have been an indigenous development as farmers took up introduced crops and introduced ideas, and as population continued to rise.

The Mississippians sometimes did utilize burial mounds, but they are most noted as temple mound builders. The built large rectilinear flat topped earthen mounds for the main purpose of placing temples, primarily of built of wood, on the top. Often several temple mounds of various sizes faced each other across a large central plaza, with other public buildings and various houses surrounding the plaza area. Though most Mississippian sites are found in the south and along the Mississippi River, eventual sites were found from Florida to Wisconsin and west to Oklahoma. Their influence was evident archaeologically throughout the entire eastern half of what is now the US.

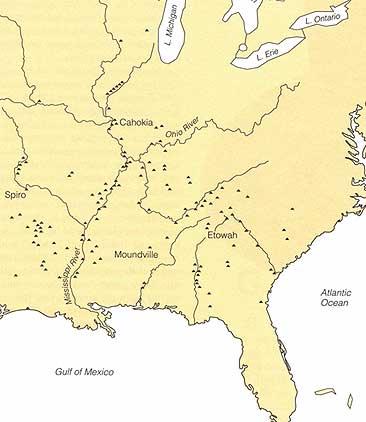

Mississippian Sites (from Price and Feinman, Images of the Past, 1993, p.263)

Many of the sites, such as Spiro, Moundville, Etowah, and particularly Cahokia (see below), are so large that they must represent powerful chiefdoms verging on becoming true agrarian states, as was the case with Hawai'i. Unfortunately, as is often the case, many of the sites were destroyed, plundered, or excavated in the early days of archaeology, when much information was lost. Click here for the story of Spiro Mounds which illustrates (interspersed with pictures of mostly replicas of Spiro artifacts) what often happened to the sites, and explains why so much is unknown of the people. Click here for more information on Spiro Mound; though not required, you should at least scroll down and look at the diagram of mound construction, and the various artifacts recoverd. (Your text discusses Moundville and Cahokia on pp. 283-194 and has additional pictures; be sure to read it also.)

Sometimes the artifacts themselves tell much about a culture, and that is certainly true of Mississippian artifacts. Part of a trade network that developed with even greater scope than that of Hopewell, and with craftsman supported by chiefs and sustained by a fully horticultural economy, the artifacts express both artistry and elements of the culture that produced them.

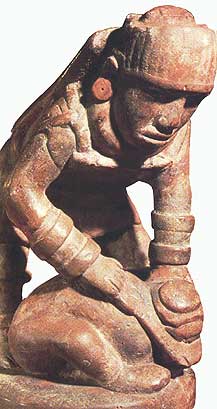

Sandstone Carving. Lines on Face Probably represent tattoos (from Lost Civilizations: Mound Builders & Cliff Dwellers, Time-Life, 1992)

l

l

Pottery human effigy (l) and Wooden Mask with shell inlay (r) (from Lost Civilizations, p.42, 56)

Conch shell cup (l) and Ceramic cup with Death's Head (r) (from Lost Civilizations, p.73 and p.74)

Large stone pipe, 8.5" by 10", the pipe depicts a man smoking a large pipe! (from Lost Civilizations, p.65)

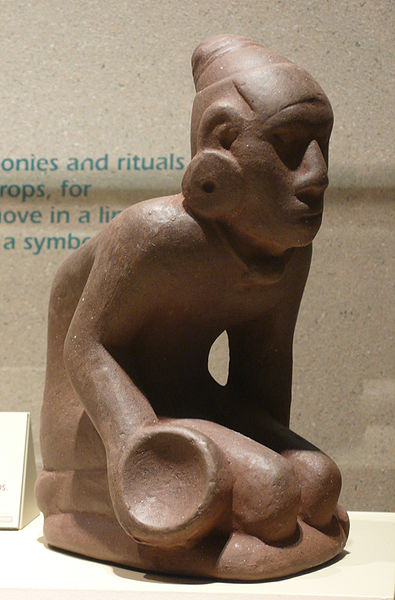

Two Human Effigy Pipes (From Lost Civilizations, p. 74 and 77)

The human effigy pipes in particular show details of Mississippian dress, decoration, and hair styles. The one above left is almost 10 inches tall, and shows a warrior or perhaps an executioner decapitating another individual. (See also p. 194 in your text) The one on the right, almost 11 inches tall, show a member of the elite wearing bead necklaces, braids, cap, and a feathered cape.

Chunkey Player about to thrown the round chunkey stone in his right hand (Public Domain photo)

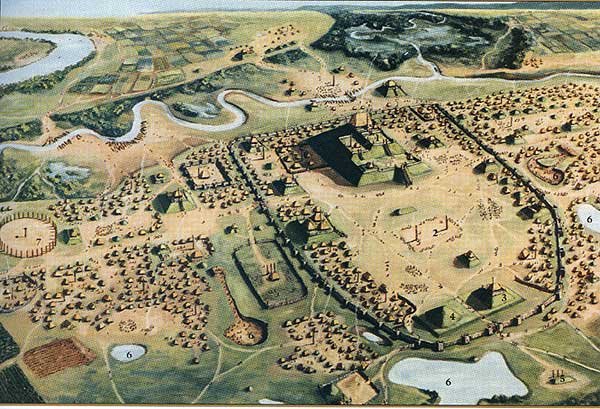

Cahokia, of all the Mississippian sites, appears to have approached the nearest to an incipient agrarian state, and certainly represents the ruling headquarters of a large and powerful chiefdom. It is the largest prehistoric site north of Mexico, and had the largest monumental structure, Monk's Mound. Cahokia is today located beside the Mississippi River in outside East St. Louis, Illinois. Below is a reconstructed plan of the site.

Reconstruction of Cahokia (from Lost Civilizations p.61)

In the reconstruction above, #1 indicates Monk's Mound (so named because in the 1800's it briefly had a Trappist monastery build on the lowest terrace), #2 represents a chunkey field, used to play a game called chunkey that used polished stones which originated in the Cahokia area around 600 AD. After 1050 AD, the game spread throughout the area labeled Mississippian on the map above, indicating Cahokia's enormous influence. Chunkey may have been played only by the elites. Numbers 3,4 and 5 indicate burial or mortuary mounds, # 6 indicates barrow pits, and # 7 a woodhenge, a circular area surrounded by large wooden pillars. Certain areas of Cahokia had been destroyed or seriously damaged before the 1960's, when a highway bisected it and some excavation was done. The rest of the site has been preserved, and much of the outline of the site mapped using remote-sensing procedures which do not require excavation and destruction.

One burial mound that was excavated is Mound 72, indicated by the #5 above. It contained three burials of elites, interned at different times. The central figure was a 45 year old male, who lay on thousands of of shell beads (shell imported from the Caribbean) as well as other grave goods, including a pile of 15 chunkey stones. He was accompanied in death by individuals sacrificed for the occasion. The bodies of four men were found, missing their heads and hands but with arms linked, and 53 women between the ages of 15 and 25. Other nearby burials substantiate that Cahokia's rulers took their retainers with them at death.

Beginning around 1100 AD a large wooden palisade was built around the central plaza and Monk's Mound. This may have kept commoners out, or have been entirely defensive to help protect the most important structures from enemies. At its height, around 1250 AD, Cahokia was inhabited by around 20,000 people, with thousands more living in smaller towns and villages near-by. It was probably larger than London at the time. After 1250 AD parts of Cahokia began to be fall into disuse, and southern sites like Moundville, Alabama became more important. By 1500, Cahokia was largely abandoned. It is not known what caused the abandonment, though increasing population resulted in many more outlying areas being occupied. Environmental problems, internal dissension, and external enemies may also have played a part, though this is unclear. With the demise of Cahokia, America north of Mexico would have to wait until the late 1700's before another city (Philadelphia) would reach the same population size.

For a chance to explore the mounds, (not required) click here. To see a 14 minute video on the mounds, not required but interesting, click here. Both are part of the larger webpage of the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site.

Mississippian sites in the southern US were thriving in 1500, and many were still occupied in the northern Mississippian area even after the abandonment of Cahokia. Large towns, occupied temple mounds, and dense populations were described by some of the survivors of the Hernando de Soto's expedition for Spain. Seeking a way to China, as well as hopefully gold, de Soto landed in Florida in 1539, with 620 men and over 200 horses. A leader in Pizzaro's brutal destruction of the Inca in Peru, de Soto utilized the same strategies as he hacked his way through at least ten southern states. Seizing stored grain and decimating fields, de Soto frequently burned towns and massacred residents; needless to say, the Mississippians fought back. De Soto himself died in 1543 along the banks of the Mississippi River, and his expedition lost more than 300 men to fighting or illness, along with most of the horses. He found no path to China, and no riches.

The effects on Native Americans were catastrophic. Though many towns were almost destroyed by fighting, the diseases left by the Spaniards spread throughout eastern North America, and brought down the highly stratified society of the Mississippians. With death rates that probably did reach the 50%-80% (or more) levels that have been recorded historically in Oceania, the remaining populations of the towns fled the sickness, and the social and religious structure collapsed. [Review the required article earlier in this unit, The Arrow of Disease.]

When Europeans returned to southern America and the Mississippi River valley, they found nothing like what de Soto and his men had described. Much smaller chiefdoms, without the monumental temple mounds, as well as even smaller horticultural tribes were all that remained. The level of craftsmanship, and the widespread trade had largely disappeared. Only the historical Natchez appeared to retain some of the social structure and religious beliefs that once united much of the continent. In short order, the Natchez also succumbed to introduced diseases.