The Austronesian language family includes 1,239 spoken languages in a vast area that includes Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Oceania, and the island of Madagascar off the coast of Africa. [Click here to see map, and the listing of languages in this family along with their current number of native speakers. Required site. Be sure to scroll down to see the actual listing of languages.] All indigenous languages spoken in Polynesia, including Hawaiian, are members of this language family. Long before the archaeological and genetic evidence began to accumulate, it was accepted by most scientists that, based on the linguistic evidence alone, Polynesia and Micronesia must have been populated by people coming out of southeast Asia.

Archaeological as well as genetic evidence now indicates that the area of origin was Taiwan, an island off the coast of China, just north of the Philippines. Around 3,000 BC, a pottery-making, horticultural society became established on Taiwan. With a distinctive assemblage of artifacts, and an ocean-oriented subsistence, their movements can be tracked via archaeological sites. By 2,500 B.C. they were present in the Philippines, on the island of Luzon, and by 2,000 BC they had expanded into the islands that are now part of Indonesia and Malaysia. By 1500 BC they began to move into the islands of New Guinea, and particularly the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomon Islands.

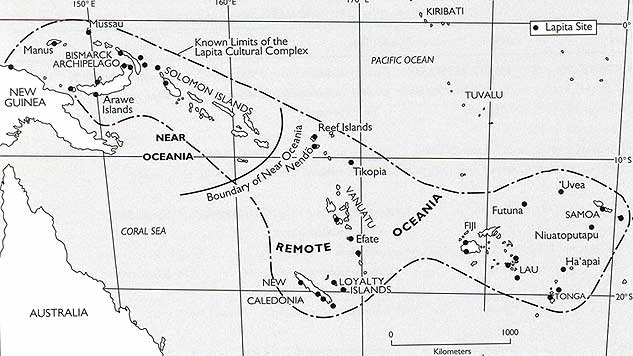

These areas were of course already occupied by horticulturalists, as just described in the previous lesson. There is an abrupt archaeological change at many sites, indicating an invasion of a people entirely different in culture. The invaders brought with them their red painted pottery, their domesticated animals of pigs, chickens, and dogs (all previously unknown in the area), and their sea-going orientation. They quickly adopted the domesticated plants native to the area. They built large villages, often with house on stilts. After a relatively brief pause, they pushed out into the Pacific to become the first occupants of the rest of Melanesia, of Micronesia, and of Polynesia. They are known as the Lapita people. [Besides linguistics and archaeology, this migration is also supported by mtDNA. MtDNA from indigenous Pacific Islanders shows that indeed they are closely related to peoples from the island areas of eastern Asia, particularly Taiwan. A specific variant of mtDNA shared by almost all Polynesians is believed to have originated in the Moluccas, or Maluku Islands just to the west of New Guinea, and now part of Indonesia. A minor variant of Polynesian mtDNA would appear to have its origins in New Guinea, and since it is shared by highland peoples of New Guinea, probably indicates intermarriage with the indigenous, non-Lapita population of New Guinea. If interested, check out the early chapters of Bryan Sykes book The Seven Daughters of Eve (2001).]

Between 1200 -1100 BC the Lapita culture expanded south into Vanuatu and New Caledonia. By 1100 BC they were moving into Fiji, and by 1000 BC they were into Tonga and Samoa. This was voyaging that had the purpose of colonization, by people who carried with them an entire complex of artifacts, and domesticated plants and animals. As archaeologist Patrick Kirch has noted, "...the Lapita colonization of Remote Oceania ranks as one of the great sagas of world prehistory." (On The Road of the Winds, p.96)

Lapita Sites (from Kirch, On the Road of the Winds, 2008 p. 96)

The culture is named after the first archaeological site where their distinctive pottery was discovered, Lapita in New Caledonia (see map above). The pottery was hand-made (ie. no potter's wheel was used) and was probably fired in open fires. In general there were two types, one a red painted utilitarian ware, and the other a red ware with elaborate dentate (toothed) stamping. The stamps had a series of fine teeth carved from wood or bamboo, and certain designs were very common, as seen below.

Lapita Pot Sherd

Other pots were found with animal and human designs. (Click here for illustration; click here for other examples.) Pottery included bowls, flat-bottomed dishes and jar of various sizes. Villages were often large, situated near beaches and garden land; houses appear to have been made of wooden posts and rafters, with thatch roofs and often open sides. Cooking appears to have been done in a separate shed.

One Lapita cemetery has been discovered, in Vanuatu. Here, headless skeletons were found, and in another area, skulls were found, some in large Lapita pots. Burials in pots are in fact another link to southeast Asia, and Taiwan, where the practice was also known to occur. Click here to read an early account of this site. To date, seventy skeletons have been found, with at least seven skulls. Initial DNA evidence indicates that some of those buried did not come from the island; at least one may have come from southeast Asia. When DNA analysis is completed, this site will likely contribute to an understanding of Lapita migration, and the effect of genetic bottlenecks on the present day populations.

A wide variety of other artifacts have been found at Lapita sites, including stone and shell adzes, slingstones, shell rings and bracelets, beads, needles, tattooing chisels, net sinkers, fishhooks and trolling lures for deep water fish. Certain types of obsidian and chert were traded long distances between islands, as they were good volcanic stone for ground stone ax and adze making, but not found on all islands. The variety of adzes particularly indicates a wood-working culture.

In terms of subsistence, the Lapita people had adopted taro, yams, breadfruit and other tree domesticates, and added to it their domesticated animals of pigs, chickens, and dogs. As they moved further into Pacific, chickens are the predominate domesticated animal, though pigs and dogs are always found. Agriculture was initially the typical swidden or slash and burn.

In addition, on all islands any existing land animals were hunted. Bird species in particular were important in the early levels, and on some islands endemic land birds were hunted to extinction. There was also, of course, great focus on the sea, with the remains of a wide variety of mollusks, reef fish, sharks, and some deep water fish such as tuna found at the sites.

In early levels there is also evidence of contact and trade between the parent and daughter colonies, with many items exchanged over short distances of less than 200 miles, and a few items traded at up to 2-3000 miles. Over time, the trade decreased, perhaps as daughter colonies became totally self-sufficient. Also with time, pottery styles in certain areas changed, while in other areas pottery ceased to be made at all (certainly not all islands had access to suitable clay, though there may well be other reasons for pottery's demise). At that point, Lapita culture proper could be said to have ended, as each island area occupied changed in unique ways. Since most evidence seems to indicate that the descendants of these people went on to populate the rest of Polynesia, it would be hard to draw a line at the end of this culture.

Why did Lapita people more so quickly across the Pacific, pausing at most for a generation or two on one island before launching another colonizing expedition to another island? While population size was no doubt increasing, particularly as people moved beyond the limits of malarial mosquitoes, it is unlikely that population pressure was a factor. There is some evidence in the pottery and the shell decoration that the Lapita was already moving into a ranked type of society (in other words, was in the process of moving from a tribal society to a chiefdom). It is therefore possible that the Polynesian emphasis on birth order had already developed, and that competition for prestige between older and younger siblings might have motivated the younger siblings to organize colonizing expeditions. Certainly these voyagers had a world view that considered oceans to be endless, but full of islands. In any event, as will be seen in a later lesson, the colonizing did not stop with the end of Lapita pottery at around 500 BC.