In New Guinea, only the coastal areas contain any sites of the Lapita people, with highland sites continuing to be occupied by the indigenous people as noted earlier. While all New Guinea was occupied by farmers, the addition of the pig still may not have the allowed the dense populations that were to characterize highland New Guinea when first known ethnographically. Pigs tend to eat what people eat, so while they were an important domesticate, it was probably a second introduced domesticate that spurred rapid population growth.

When Europeans first penetrated into highland New Guinea, they found an extremely large and dense population of tribal horticulturalists, raising sweet potatoes in huge quantities, and both eating sweet potatoes and feeding them to their pigs. The sweet potato can be grown over a much wider variety of soils and climatic conditions than taro, and its introduction was a boon both to people and pigs. The sweet potato however, is a South American domesticate, as you have already read. It reached eastern Polynesia prior to any Europeans (more on that in a later lesson), but its presence in highland New Guinea was probably due to an introduction in Southwest Asia by Portuguese explores. Diffusion into highland New Guinea allowed the population to increase to several million people. There New Guinea rapidly elaborated the tribal "big man" system that ultimately contributed to anthropologists understanding of tribes. Unlike many other areas of the Pacific, the cultures of much of New Guinea, particularly the highlands, remained as relatively egalitarian tribes, with little evidence of the ranked chiefdoms so common in much of the rest of Oceania.

Melanesia was as already discussed home to many Lapita sites, as well as a large population of earlier horticulturalists. The mixing and melding of these two influences, through time and thousands of islands, resulted in an enormous cultural, linguistic and physical diversity. While still poorly known archaeologically, chiefdoms did develop in Melanesia during the time period under consideration. Archaeologically, one of the most interesting sites is on Efate Island, in the center of Vanuatu, with the grave of a chief named Roy Mata.

This site dates from around 1250 AD, and was still surrounded by oral tradition, much of which was demonstrated to be valid by archaeological excavation. Oral tradition said that this site was the grave of a chief, who supposedly had brought peace to the region. After his death, his body was displayed in several villages, and he was than buried along with some of his kin and representatives of other kin groups. Not all of these people, according to tradition, accompanied him voluntarily. The men were stupefied with kava prior to burial, but women were buried alive while fully conscious.

Upon excavation, the central male figure was indeed found with more than three dozen people, most in male/female pairs. The male skeletons were laid out on their backs, while the female skeletons were often found contorted, as though they did indeed die while buried alive.

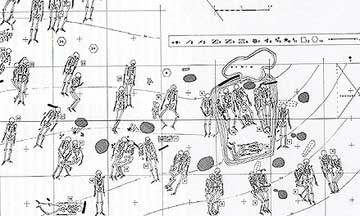

General plan of Roy Mata burials (From Kirch, On the Road of the Winds, [2000] p.140)

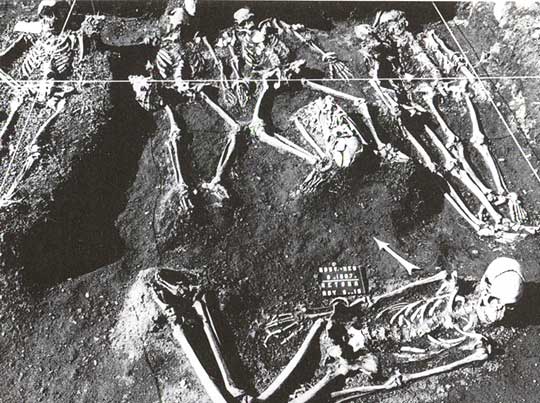

The actual chief is in the enclosed group of skeletons at center right of sketch above, and is show below with a bundle burial (possibly of an ancestor) between his legs (See below).

Roy Mata, with Ornaments on his Chest, and Companions [from Kirch, p.141]

Roy Mata is also buried with shell bracelets, a bead necklace, and rows of shell beads around his waist, which had probably been connected to a garment at one time. On his wrists were bracelets of pig tusks. Clearly this is the burial of a chief, and represents a level of social stratification and political control that was not characteristic of earlier Melanesia. Most interpretations are that this was a development without outside influence, though some archaeologists belief that Roy Mata may have been an immigrant from one of the contemporary high chiefdoms of Polynesia.

Micronesia consists of some 1200 islands, many very small, somewhat to the north of Melanesia and New Guinea. While all languages spoken in Micronesia belong to the Oceania branch of the Austronesian language family, linguistic analysis appears to support three separate migrations into the area. Archaeological evidence appears to confirm this.

The first migration took place as early as 2,600 BC by ancestral Lapita people coming directly from southeast Asia, perhaps from Taiwan or Philippines. This migration would be in the first stage of ancestral Lapita migration from Taiwan. The second migration, perhaps around 100 BC, was of an established Lapita culture moving up from the Solomon Islands to the south, carrying with them the full complex of Lapita horticulture, stilt houses, and red-painted pottery. These colonists gradually moved onto most of the islands, including coral atolls, and began domesticating and environment in some cases totally lacking in vegetation. The third migration, primarily onto Yap Island, took place from the Bismarck Islands to the south.

While many of the small islands, particularly the coral atolls, could not support large populations, on some of the larger island there was the usual increase in population. Though tribes persisted in some areas, other areas went on to develop chiefdoms, with megalithic architecture, elaborate burials, and status symbols for the elite.

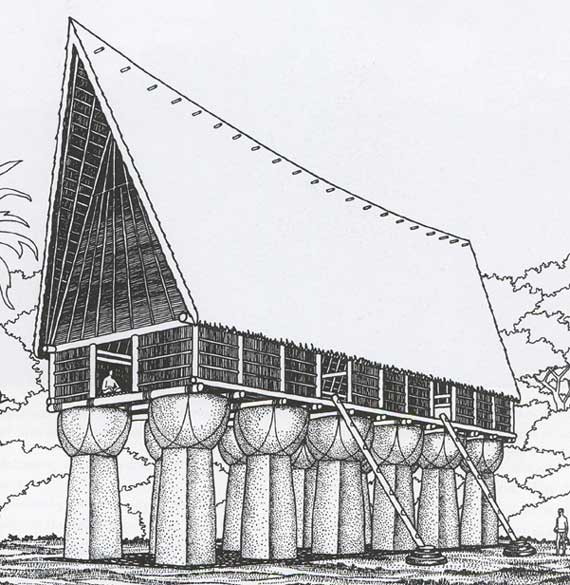

In the Marianas, on several islands, large carved limestone columns from four feet to as tall as fifteen feet have been found, with square bases and flat tops, and arranged in two parallel rows. These appear to have been the supports for A-frame houses of wood and thatch, the homes of the elite. (Click here for photos of the columns from Guam and Tinian.) Below is the a drawing of the how the most famous site, the House of Saga on Tinian, might have looked.

Drawing of House of Taga, with its 12 carved limestone columns, Tinian Island (from Kirch, p.187)

Yap is particularly well known for its stone "money", which were really display items indicating the wealth of competing chiefs. Yap was a strong chiefdom from around 800 AD to 1400, controlling several islands, with tribute flowing to Yap in stratified redistributive exchange. A complex of large stone house platforms for the elite, with paved stone terraces and paved trails connected plazas where the large stone discs (some as large as ten feet in diameter and weighing thousands of pounds) were displayed. The limestone to make the discs was imported from Palau (over 250 miles away) via canoe, and required an enormous amount of labor to carve and transport.

On the Caroline Islands, Pohnpei (now along with Yap part of the Federated States of Micronesia) is one of the best known sites of a high chiefdom, with elaborate ranking and social stratification, dense population (perhaps as high as 30,000 people), and economic specialization developing by 1000 AD. By 1200 AD the island had been united under one chief, with its center at a site called Nan Madol. Nan Madol is comprised of interior courts and enclosures, tombs, artificial islands and canals, and comprised the residence and burial structures for the ruling elite. Construction was of basalt boulders and in many cases basalt slabs.

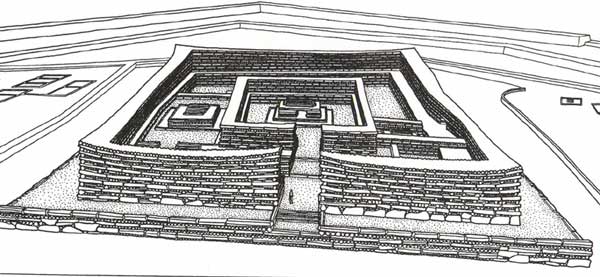

Photo of the Ruins of Nan Madol (from Kirch p.196)

Drawing of Main Burial structure, Nan Madol. Containing individual crypts, this artificial island measures 237' by 189 ' at the base, and rises 23' above the surrounding canal. (from Kirch p.197)

Nan Madol was abandoned by 1600 AD (prior to European contact), perhaps due to competing chiefs and internal strife. The evidence of intensification of horticulture prior to 1600 AD might again indicate population increase and possible collapse. There is insufficient archaeological evidence to say.