The three domesticated crops of maize, beans, and squash, established by 3000 BC in southern Mexico, spread northward relatively quickly. While a secondary domestication center almost certainly developed in what is now the eastern United States, with the domestication of sunflower, a species of squash, goosefoot and marshelder (see p. 258-59 in text), it was the introduced domesticates from the south which fully established horticultural tribes and ultimately chiefdoms across the southwest and eastern U.S. [NOTE: The lessons will summarize, and add to, much of the information in Chapter 7 in the text; however my focus is more on the spread of maize domestication. As a result the lessons start with, rather than end with, the American southwest. Be sure to note the several required links in this and subsequent lessons.]

Northern Mexico and the southwestern United States are today mostly an arid or semi-arid environment, with an annual rainfall of less than 10 inches in the drier parts of New Mexico and Arizona. Rainfall is sporadic, rivers often intermittent, and soils thin. It is at best a marginal area for agriculture without irrigation, but when domesticated maize and eventually squash and beans were introduced from central and southern Mexico, the result was the development of vigorous tribes and chiefdoms.

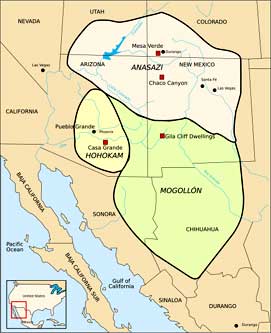

Today archaeologist's have divided these horticulturalists into three (sometimes four) groups, Hohokam, Mogollon, and Anasazi or Ancestral Pueblo. More or less contemporary, each name represents a slightly different geographical areas, and somewhat different common elements of culture. There were many archaeological sites within each cultural area, and widespread trade. To what extent there was political unity within any of the cultural areas is difficult to say. The map below shows the general extent of the three major groups.

Anasazi (Ancestral Pueblo), Mogollon, and Hohokam (Map from Wikipedia Commons)

In this brief survey of these three cultural areas, pay particular attention to their art and architecture, best done by clicking on all links, required or not, and looking at any pictures.

Farming started in the Hohokam area as early as 1 AD, with small groups of farmers raising maize and beans. The introduction of new bean species, plus squash and cotton by 300 AD led to a continual increase in population. Though influenced by the development of agrarian states in southern Mexico, for the most part Hohokam appears to have been an indigenous development from foragers who had occupied the area since 9,000 BC.

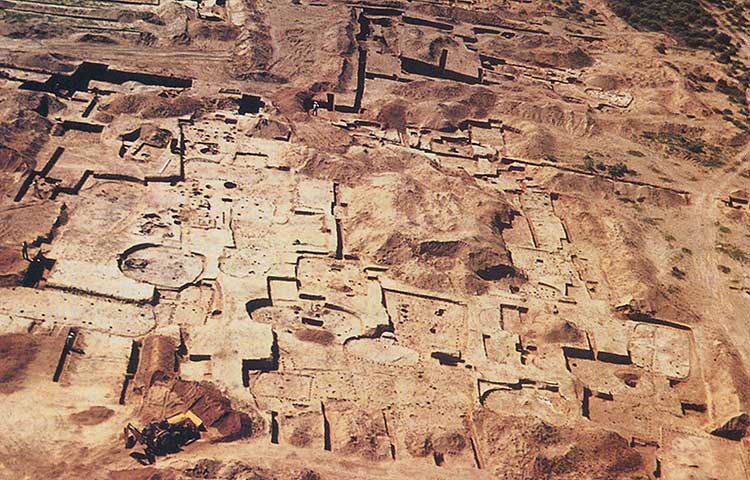

Major sites include Casa Grande and Snaketown in Arizona (see pp 300-305 in text for more on Snaketown). These large towns once housed several thousand people each, and showed considerable influence from southern Mexico. Snaketown contained two ball courts, a large central plaza, and small ceremonial structures. Over 200 ball courts have been found at Hohokam sites, rectangular, partially sunken courts some 180 feet long and 65 feet wide. Here citizens probably gathered to see games played with a small rubber ball; the object of the game was to get the rubber ball through a small ring on high on the side of the court (perhaps without using hands and feet to do so.) This game, as we will see in the next unit, is characteristic of many Mexican and MesoAmerican agrarian states.

Snaketown excavation in 1964 (backhoe at lower left is moving backdirt piles, not excavating!) From: Lost Civilizations: Mound Builders & Cliff Dwellers, Time-Life Books, 1992, p.94

Snaketown and Casa Grande, as well as other southwestern sites, probably represent the development of chiefdoms by 1000 AD or earlier, and artifacts found at these sites indicate extended trade networks with shells from the Gulf of California, and parrot bones and feathers as well as copper bells from southern Mexico. Click here to view some of the jewelry and pottery recovered from Casa Grande. (Required site, but you only need to look at the pictures.) Hohokam may also have been the first culture to develop acid etching, with shells imported from the Gulf of California etched with a mild acid, probably derived from fermented cactus juice.

Etched Shells dated at 1000 AD. From Lost Civilizations, p. 103

Hohokam survived by spreading out their population along the rare streams and shallow wells of Arizona, and they developed an extensive irrigation system. Over 400 canals have been discovered in the Phoenix area alone (with the help of satellite photography), most of them over seven feet deep and no more than 10 feet wide, though a main canal has been discovered over 12 miles long, 16 feet deep, and 80 feet wide. The canals themselves indicate the probable chiefdom organization of the culture, with chiefs able to mobilize the necessary labor to build and maintain these canals.

Like Hohokam, the cultural group called Mogollon was influenced in many ways by southern Mexico, and may reflect at least some migration of peoples into the area. Mogollon developed with distinct pottery styles (particularly from the sites of the Mimbres pottery styles), and developed complex stone buildings with 150 rooms or more. Later the open sites were abandoned, and much of the population built cliff dwellings in areas like the Gila River cliff dwellings, now a national monument. (Click here and then click on "Images of Gila Cliff Dwellings View Slideshow", for a quick tour.) The pottery styles of the region around Mimbres are particularly noted, though most of this pottery was made to be buried with the dead, particularly the elite. A hole was usually punched in the bottom of funeral pots, perhaps to release the spirit.

Mimbres pot with stylized mountain sheep (from Lost Civilizations p.99)

A Mimbres effigy pot, perhaps used to store seeds. (Lost Civilizations, p.98)

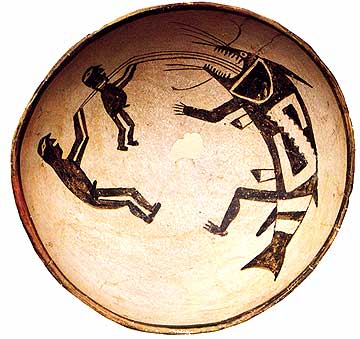

Mimbres pot (from Lost Civilizations, p.98)

The pot above probably depicts an oral myth still prevalent after Europeans came into the area, and represents Hero Twins trying to prevent drought by pulling rain from a monster called Cloud Swallower. It is likely that most of the ceremonial buildings in Mogollon, Hohokam, and Ancestral Pueblo were focused on ceremonies to ensure adequate rainfall. In the case of the Mimbres area, horticulture was originally practiced on a flood plain, where the water table was high and periodic flooding provided adequate moisture for the plants. However, expanding population forced horticulture to expand outside the flood plain, and drought brought a quick collapse and abandonment of Mimbres sites around 1130 AD.

The third location in the American southwest where farming spread very early and then went on to develop chiefdoms centered on the "four corners" area (where the present states of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah meet.) Here between 500 and 1300 AD the large sites of Chaco Canyon, Canyon de Chelly, Aztec Ruins, and Pueblo Bonito (in Chaco Canyon) grew and eventually were abandoned. Great sites like Mesa Verde were inhabited for some 600 years, though in general the period of cliff dwellings started only after 1200. Click here to see pictures of the architecture of Mesa Verde, and here to see pictures of artifacts. (Click on the pictures to enlarge.) Both of these are required sites. (Also review pp. 306-310 in the text.)

Anasazi was the name given to these people by the Navajo, newcomers to the area after 1600. The term has the connotation of "enemy", and it has generally been replaced with the term Ancestral Pueblo, since these ruins as well as those of Hohokam and Mogollon represent the ancestors of the modern Pueblo Native Americans, such as members of the Hopi and Zuni tribes. Pueblo of course is the Spanish word for town or village, and without question the Spanish did more harm to the descendants of Ancestral Pueblo than the the Navajo ever did. Modern Pueblo call their ancestors the Hisatsinom, but I will go along with your text and the term Ancestral Pueblo. By the time the Spanish came, the sites noted above had been uninhabited for almost 200 years.

Initially food was plentiful. People grew maize, with some beans, squash, and cotton, channeling run-off from rain. The turkey was domesticated, and the diet supplemented by hunting deer and antelope and gathering pinyon nuts from the abundant forest of upland areas. As the population expanded, diverting water and clearing vegetation led to serious erosion and episodes of arroyo-cutting, a problem that was temporarily solved by building dams across side canyons and the main canyon in Chaco.

Chaco Canyon, and the large site of Pueblo Bonito, became the center for a large chiefdom after 600 AD. Pueblo Bonito eventually contained stone structures some six stories high (the tallest buildings in the United States prior to the 1880's), and contained some 600 rooms. Roof supports for the rooms contained logs 16 feet long and weighing up to 700 pounds each. The Great Kiva or ceremonial chamber at the misnamed Aztec Ruins (there was no Aztec influence) and the stone work of the rooms with their perfectly aligned doors is still impressive. (Click here and then on View SlideShow for a quick tour of the Aztec Ruins, in New Mexico, and the reconstructed Great Kiva. Use the + sign to advance slides quickly. Required site.)

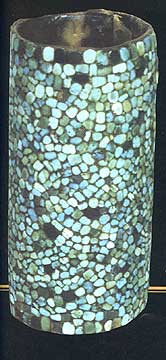

As the population at Chaco Canyon grew, it became more and more dependent upon the surrounding area for imports, including maize, pottery (a local wood shortage perhaps prevented the Canyon population from producing pots), turquoise from the mountains of New Mexico, and luxury goods for the elite, such as shells, jewelry, parrots, and copper bells from southern Mexico. One room in Pueblo Bonito contained the burials of 14 individuals, with 56,000 pieces of turquoise and thousands of shell beads.

Anasazi flute, carved from bone (Lost Civilizations, p.124)

Basket Inlaid with Turquoise from Pueblo Bonito (from Lost Civilizations, p.127)

From the garbage found near what are presumed to be chiefly residences, it appears that the chiefs ate better than other people, with a much higher proportion of deer and antelope (taken by hunting) than found in the garbage of the common people. Physically, the burials of chiefs, with their thousands of turquoise beads, were of people that were taller and better nourished than commoners. (All of this was pretty much true of chiefdoms everywhere.)

By 1000 AD, Chaco Canyon had been almost completely deforested and the large logs (now of ponderosa pine) for construction were imported from 50 or 60 miles away. The people of Chaco had to rely on food from surrounding areas, as the population had grown too much to be self-supporting. The deforestation of the area is documented, and dated, by the activity of pack rats, whose nests of sticks, plant remains, and feces are cemented together with their urine, and can both be dated and analyzed by paleobotanists. A drought began in 1130 AD, and the last construction beam anywhere in Chaco (imported, of course) is dated at 1170 AD. Chaco was totally abandoned shortly thereafter. Before abandonment there may have been depopulation via starvation; human coprolites (dried feces) have been found containing the entire skeletons of headless mice, not a normal part of Chaco diet.

Many Ancestral Pueblo sites survived until 1250 AD, but there was increasing evidence of environmental depletion and of warfare. Defensive walls and moats appear at some sites, settlements are built atop steep cliffs that are more easily defended, villages are found that have apparently been deliberately burned and contain unburned bodies, all evidence of warfare. There is evidence of cannibalism as well. At one site, unburied bones appear to have been cracked to extract the marrow, other bones have smooth ends indicating cooking in pots, and coprolites have been found containing human muscle protein. (The dry climate of the southwest is perfect for preservation!)

By 1500, all major sites of Hohokam, Mogollon, and Ancestral Pueblo had been abandoned. This was due to a combination of deforestation (particularly for Ancestral Pueblo), erosion, salinization of soil (particularly for Hohokam), and a rising population that ultimately could not survive a natural climatic change. The modern Pueblo developed a truly sustainable lifestyle, less destructive of the environment, and in various ways restrained population growth.

In all, the Pueblo have sustained agriculture in one of the most marginal areas of the world for close to 2,000 years, but not without cost. It is worth remembering that the longevity of Ancestral Pueblo, Hohokam, and Mogollon is still longer than the time Europeans have been in North America.