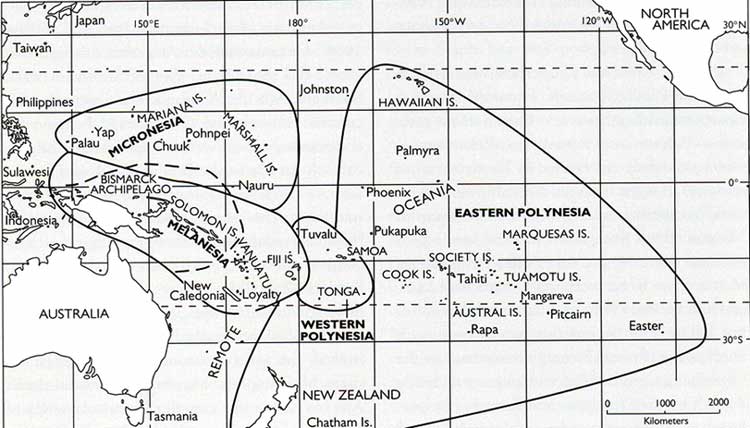

During the Pleistocene, humans began the populating of the Pacific Islands, a task not to be completed until after 1500 BC, when the Lapita people swept down from the north, stopped briefly in the already populated areas ("Near" Oceania), and continued into unpopulated "Remote" Oceania. [Your text covers all of this in one page, 144; so read all lessons closely!] Traditionally the islands of Oceania have been divided into three geographic areas: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia, as shown on the map below. [To see modern nations and territories in Oceania, click here.]

Oceania Map, from Patrick Kirch On the Road of the Winds (2000) p.6 [Heavy Dashed Line Separates Near and Remote Oceania]

Oceania Map, from Patrick Kirch On the Road of the Winds (2000) p.6 [Heavy Dashed Line Separates Near and Remote Oceania]

These three areas are best thought of as useful geographic areas, since with the partial exception of Polynesia, within each area there is tremendous physical, cultural and linguistic diversity. The earliest European explorers of the area were impressed with the linguistic and cultural similarities of the Polynesians, and linguistic similarities to cultures further to the west in eastern Asia had long led scholars to believe that the area had been settled through island-hopping settlers moving from west to east across the Pacific. Until the mid-twentieth century however, this movement was believed to have been very recent. Hence there could be no sites with stratigraphy demonstrating cultural change. Oceanic cultures, it was assumed, really had no history; they had always been the way they were known by the earliest European explorers. This assumption of a recent occupation and no cultural change, together with the difficulty of actually doing archaeology over the vast area of Oceania, meant that relatively little archaeology was attempted.

Bishop Museum archaeologist Kenneth Emory was excavating Kuli'ou'ou Rockshelter on O'ahu at the time (1951) that radiocarbon dating was first developed. Sending a charcoal sample to be dated, he was astonished and delighted to receive a date of approximately 1004 AD, the first radiocarbon date in Polynesia. A year later, another archaeologist working on a stratified site in New Caledonia called Lapita, used the new method to date charcoal associated with unusual pot sherds (broken pieces of pottery). With a date of 850 AD, it became clear that Oceania had a history, and archaeological work increased. Though an enormous amount of work has been done since the 1950's, many areas are still poorly known, or almost totally unexplored. Nonetheless, through archaeology, oral tradition, linguistic and genetic studies, a much clearer picture has emerged.

Oceania incorporates several climatic zones (temperate, subtropical, and tropical), as do continents. Its islands vary from high volcanic islands to coral atolls barely a few feet above sea level. There are frequently major climatic differences from leeward to windward sides of islands, and on the high islands elevation creates significant differences in temperature and rainfall. The land was separated by vast stretches of ocean. Yet almost every scrap of land was occupied, almost always successfully, by humans who developed a wide variety of cultural adaptations to the ocean environment and local island environment. In this section of lessons, we will be exploring these adaptations, up to 1500 AD, in significantly more detail than the one page presented in the text.