Easter Island, more commonly known today as Rapa Nui, is the most easterly (and isolated) point of Polynesia. It is 1,300 miles from the nearest island of Polynesia, Pitcairn Island. It is over 2,300 miles from the coast of Chile in South America. Rapa Nui is a small volcanic island, only 66 square miles, and its maximum elevation is 1,670 feet. Yet it is perhaps the most famous island in Polynesia, known for its carved stone statues, most from 15 to 20 feet high, but with the largest at 70 feet . Weighing anywhere from 10 to 270 tons, these statues (called moai) depicted the torso and face of long eared men, and almost 300 of them were at one time erected on stone platforms (called ahu) around the coast of the island. (Click here for map of Rapa Nui.) Almost 400 more statues are found in various stages of completion in the Rano Raraku stone quarry (along with stone picks and other tools used for carving), and some 90 are found "in transit" along the trails and tracks out of the quarry.

Moai on Easter Island, with its back to the see, as was typical.

Rapa Nui is well-known in archaeology and history for a couple of other reasons. One is the activities of the Norwegian archaeologist Thor Heyerdahl, (1914-2002) and his theory that the Pacific Islands had been populated by people coming from Peru, British Columbia, and possibly other points along the western coast of the Americas. Heyerdahl was familiar with Easter Island (he was one of the early archaeologists to do excavation there) and claimed that the megalithic statues, and the exceptionally fine stone work facing found on some of the platforms, were proof that people from the Inca state in Peru had populated Polynesia and the rest of Oceania.

Even in the mid-20th century, before the beginning of much archaeology in the Pacific, this claim was rejected by most archaeologists. The linguistic evidence indicating an ancestry of Oceanic peoples far to the west near Asia was already available, cultural evidence indicated few similarities with South America, and the plants and animals domesticated in Oceania were already believed to have their origin in southeast Asia or New Guinea. In any case, much about Heyerdahl's theory evoked ethnocentric and racist notions that "someone else" other than the people actually living in the area, had made the megalithic structures. "Someone else" had to have shown the people indigenous to Rapa Nui how to make megalithic structures and fine stone working. (Historically that "someone else" has included not only the Inca, but the Egyptians, Chinese, people of the mythical lost continents of Atlantis and Mu, and ancient astronauts from another solar system.) Enough was known about the culture of the Inca, however, to also say with some validity that the Inca did not have ocean-going vessels, and were not known for their orientation to the sea.

In 1947 Heyerdahl decided to address the last of these issues, and built a balsa wood raft in the style of the Inca. Sailing from Peru, Heyerdahl and his crew drifted on the slowly-sinking raft for 101 days, finally ending up on an atoll in the Tuamotu Archipelago. This was the earliest of several dramatic efforts in experimental archaeology for Heyerdahl, and he wrote a deserved best-seller, Kon Tiki (after the name given to the raft) about his adventures. He had proven that people could have drifted from Peru to Easter Island and beyond, but not that they did. In 1999, the Hokule'a reached Rapa Nui after a difficult 17 day sail from Mangareva. (Click here for a highly recommended article on the difficulties presented, and the reasons for Rapa Nui's isolation after colonization. Archaeologist Ben Finney wrote this article before the Hokule'a's voyage to Rapa Nui.)

The Balsa Raft Kon Tiki, 1947

Once discovered historically, Easter Island experienced some of the most tragic depopulation of any area in Oceania. The European discovery of the island was by the Dutch explorer Roggeveen, who arrived on Easter day in 1722. He didn't stay long, though he did note that there were only low trees on the island. James Cook also visited Easter in 1774, only the third European to do so, and noted that many of the statues had been thrown down, though others were still erect. After that, Rapa Nui was frequently visited by European ships.

There is no way to know for sure the population before 1722, but archaeological estimates based upon the number of house foundations range from 6,000 to as high as 30,000. The evidence of intensive agriculture on Rapa Nui make estimates of at least 10,000 to 15,000 people seem quite reasonable. The earliest reliable census was not until 1864, when a missionaries found approximately 2,000 people, shortly after a smallpox epidemic was reported to have killed "most" of the population. The same ship which left smallpox went on to the Marquesas and left an epidemic that was reported to have killed 7/8ths of the population on those islands. There were at least two earlier recorded epidemics on Rapa Nui, and probably several unrecorded ones. By the time of the 1864 census, Peruvian slave ships had also kidnapped 1,500 people in raids between 1862-63. From 2,000 people in 1864 the population declined to a mere 111 islanders by 1872, primarily due to introduced diseases. This story was certainly not totally unusual for Polynesia; the diseases of Asia were not able to follow small groups moving into islands separated by vast expanses of ocean, and when the Lapita people moved out of Melanesia, they left even malaria behind them. As a result, there was no evolved immunity to "old world" diseases. However, the extreme depopulation of Rapa Nui meant that much oral tradition was lost as adults died before it could be passed on. According to some archaeologists, the horrendous depopulation caused by European contact also meant that people were less willing to accept the evidence that islanders had helped create their own ecological disaster prior to the Europeans.

Currently there is great debate on when the Polynesians reached Rapa Nui, though artifact comparison indicates they did so via Mangareva, an island in the southern part of the Austral Islands south of Tahiti. Analysis and dating of pollen cores indicates the onset of human forest clearance at around 200 AD; linguistic analysis would place the date at 300-400 AD, and AMS radiocarbon dating from bones at the oldest levels of a beach site are dated at 900 AD. More recent radiocarbon dating form the presumed oldest site in Rapa Nui, by UH archaeologist Dr. Terry Hunt, has yielded a date of 1200 AD. Your text (p.144) gives a date of 500 AD, though does not note what it was based upon. Given the wide variety of dates from different archaeological expeditions that indicate occupation at least as early as 600-800 AD, it is possible that the date of 1200 AD is not correct, and the Rapa Nui was occupied by 900 AD, at least. Clearly a definitive answer must wait on more research.

Once Rapa Nui was occupied, there is no archaeological evidence of further contact with its founding island, a situation unusual for Polynesia but supported in this case by oral tradition as well as an analysis of mtDNA from the Pacific rats brought by the early settlers. The voyagers brought with them taro, yams, possibly the sweet potato, bananas, sugar cane, and chickens (pigs were apparently not present on the early voyaging canoes). They found an island that had 22 now extinct plant species, including a species of large palm over 65 feet tall, even though Easter was drier and windier than most Polynesian islands. There was also a plentiful land bird population, as well as sea bird nesting areas, which was common for many areas of Polynesia, but the shores of Easter had fewer reef fish than off most Polynesian islands.

After initial occupation, midden sites show that wild bird population were heavily utilized, and there is evidence of deep sea tuna and porpoise as well as reef fish, and the domesticated chicken. Later, the middens show a decrease in wild birds, an absence of deep sea species, and an increase in chickens. It is probable that deforestation meant that canoes capable of deep sea fishing could no longer be built; certainly Cook in 1774 described small leaky canoes that were not comparable to the large deep-sea fishing canoes that he had seen in other areas of Polynesia. The people built stone houses for the chickens, and numerically these increase over time, indicating more dependence upon their sole domesticated animal.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the carving and erection of the moai began around AD 1100, and that the earlier moai were smaller than the later ones. The statues appear to be associated with the houses of a chiefly elite, which were often found immediately inland of the statues. It is probably that the moai represent deified ancestors, and their descendants wished to be under their gaze. Oral tradition as well as archaeology indicates that the island was divided into some 11 descent groups, each headed by a chief who was in status competition with other chiefs. Yet all chiefs had access to the one quarry where the statutes were carved, and to another quarry where the red stone often used to carve cylinders (that were placed atop the flat heads of the moai) was found.

Experiments at moving and erecting the statues, as well as surviving oral tradition, indicate that the statues were moved along parallel wooden rails, with fixed rails joining them at intervals. (In Hawai'i large canoes were also moved in this manner.) If that is the case, the manpower involved in the entire sequence of carving, moving (with the assistance of rope manufactured from fibrous tree bark) and erecting these statutes on platforms needed enormous food resources. In addition, a considerable quantity of wood from big trees would have been necessary. More recent experiments by Dr. Hunt have indicated that 15-20 men could have "walked" the statues between them, much the same way two men could "walk" a refrigerator into a new location, though it does not appear this method was attempted with a near 70 foot tall stature. (See The Statutes That Walked: Unraveling the Mysteries of Easter Island, by Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo, 2011)

The main building period lasted until approximately 1500 AD; after that, it appears to have ceased, leaving many statues unfinished in the quarry. From 1500 on, there is evidence that many statues were thrown down, often in such a way that their heads broke off. Statues were sometimes incorporated into newer walls or platforms. There is evidence of intense intergroup raiding, in that the finely worked basalt foundation slabs of the elite houses were pulled apart, and used to fortify subterranean caves and lava tubes. Charred and broken human remains are found in late period middens, and there is an increase in obsidian spear points.

Evidence from pollen, archaeological sites, and direct dates on palm nuts, indicate that before 1600 all the large trees had vanished. (And in 1722 Roggeveen saw no trees over ten feet tall.) Horticulture had intensified, with stone lined pits being used to compost and grow crops, a complex water diversion and irrigation system, stone windbreaks, excavated depressions for planting taro, and lithic mulching to preserve moisture for the plants. All these methods were ingenious ways to intensify production in a difficult environment. Yet there is some evidence that population also decreased, and it is possible that the island was no longer able to support its larger population due to a decline in food resources. Oral tradition as well as archaeological evidence indicates that by 1680 the chiefs had been overthrown by military leaders, and that Rapa Nui entered a period of civil war.

Some claim that the deforestation must have been the result of unrecorded Spanish and other European visitors after Magellan first entered the Pacific in 1521. There is no evidence of such contact either in European records or archaeologically, but that does not rule out the possibility. Certainly any contact with Europeans might have caused an epidemic, and population decrease; it is difficult to say how one or two ships could have caused deforestation. In any case, the archaeological evidence indicates land bird extinction before 1521, as well as the disappearance of porpoises and tuna from the diet. Pollen studies indicate deforestation was well advanced before 1300, and there are no radiocarbon dates on palm nuts more recent than 1500. Hunt has hypothesized that the Polynesian rat, brought by the first settlers (in 1200 AD, according to Hunt), were primarily responsible for the demise of the large tress, particularly particularly the tall palms. Rats will feet on seeds and young tree shoots, and in the absence of any predator Hunt states there was a rat population explosion. While people certainly contributed to deforestation, they were not the major cause, according to Hunt.

While rats may certainly have contributed, in the absence of definitive evidence, it makes no sense to simply say that Rapa Nui peoples would not have destroyed their resources; all over the world horticultural people, including Polynesians, caused local deforestation and depletion of their environment to some extent. On the smallest of Pacific islands, with fragile ecosystems, the effects were simply felt more quickly than in continental areas such as southwest Asia or China or Europe or the Americas. As an example, consider Mangareva and its subsidiary islands of Pitcairn and Henderson.

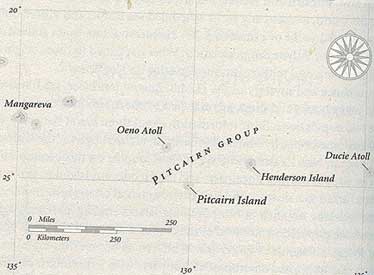

Mangareva, probable source of colonization for Rapa Nui, is an isolated area even by Polynesian standards. Settled at least by 800 AD, Mangareva was in contact, via the Tuamotus, with Tahiti and particularly the Marquesas through at least 1300 AD. During that time, it also maintained trade with its two outlier islands, tiny Pitcairn 300 miles to the southeast, and 100 miles further, the even smaller Henderson Island.

Map With Locations of Mangareva, Pitcairn, and Henderson (from J. Diamond, Collapse, p. 122)

Mangareva archaeologically has the reputation of having the most degraded environment in Polynesia. Though a relatively small series of islands, Mangareva originally had rich natural resources. It had forests capable of providing wood for large ocean-going canoes, it had valley areas for taro cultivation, slopes for sweet potato and yam production, and higher areas for breadfruit and banana. It had a particularly rich lagoon, with plentiful black-lipped pearl oyster both to eat and to manufacture excellent tools, including fishhooks. It had plentiful coarse basalt for building and for oven stones. However, there was no fine-grained basalt for adzes, and little obsidian.

Fortunately, Pitcairn, though only 2.5 sq. miles, was a volcanic island with both fine-grained basalt of the kind needed for adzes and other stone tools, and obsidian. Its steep slopes did not make it prime land for agriculture, and it had no reef. Nearby Henderson, composed entirely of an upthrust coral reef, had no basalt of any kind, little soil, and no permanent fresh water supply, but it did have an excellent reef and the only turtle-nesting area in the southeastern Pacific. Archaeological evidence indicates that Henderson did support a permanent population, though this was only possible due to trade.

According to chemical analysis of the sources of basalt adzes, Mangareva continued to trade in fine-grained basalt with the Marquesas and the Society Islands, as well as with Pitcairn. Pitcairn also supplied the more populous Mangareva with obsidian. Henderson imported adze basalt from Pitcairn as well as obsidian, and coarse basalt for oven stones from Mangareva. Both Pitcairn and Henderson were dependent upon Mangareva for the pearl oyster shell to make fishhooks and other tools, as well as no doubt for basic domesticated food supplies which were difficult to produce, particularly on Henderson. Henderson however could supply Pitcairn with fish and shellfish, and both Pitcairn and Mangareva with live sea turtles. It is also likely that the two small islands, which never supported more than a few hundred people, were dependent on Mangareva with its larger population for marriage partners for their children.

Trade between Mangareva and the Marquesas continued at least to 1300 AD, but by 1500 AD all trade between Mangareva and any other island had ceased. All large trees on Mangareva had been removed, and no large canoes could be manufactured. At first European contact in 1797, the Mangarevans had no canoes, only rafts. Soil erosion from the slopes into the valleys had destroyed some of Mangarevans ability to produce food. With too many people and too little food, oral tradition records that the hereditary chiefs were overthrown, and power seized by competing nonhereditary military rulers.

The results of environmental depletion on Mangareva were even more devastating for Henderson and Pitcairn. On Henderson, the most recent layers indicate no trade with either Mangareva or Pitcairn. Henderson trees were too small to make canoes. Oven rocks were made from limestone, coral, or clam shells--none of which hold heat well, and all of which are prone to cracking. Tools and fishhooks all had to be made of the small shell available locally. Diet could not be supplemented with supplies of domesticated food from other islands. Yet archaeological evidence indicates people survived on Henderson for perhaps a century or more, maybe still looking for those canoes that never came. A boat from a Spanish ship in 1606, the first European contact, recorded that Henderson was deserted. Pitcairn is less well known archaeologically, but when the mutineers from HMS Bounty arrived there in 1790, Pitcairn was also uninhabited.

I thought about Henderson recently when I went to a "food sustainability" workshop on the Big Island. Hawai'i today imports over 90% of its food, and grocery stores and their warehouses actually hold a surplus of only a week or two at most. Most of the remaining 10% of our food produced here is dependent upon feed or petrochemical fertilizers and pesticides that must also be imported. What would we do if we couldn't get those imports? I am convinced that Hawai'i did indeed at one time support a population very close in size to its present population, and did so in a sustainable fashion. There is some comfort in the thought that presumably we could do so again--at the cost of changing almost everything about our culture. That is an option that Henderson did not have. However, not all cultures always make the right choices, as we will see in considering other areas of the world.