As in western Asia, early horticultural tribes, such as the Yangshao Neolithic site of Ban-po, were quickly followed by larger and larger chiefdoms. As in other areas, chiefdoms developed to intensify production in order to support ever larger populations. Ultimately, some of these chiefdoms began to acquire more and more of the traits of an agrarian state.

China of course had its own oral traditions, which were eventually written down. According to these historical texts, the late Neolithic of Longshan was followed in northern China by what is known as the San dai, or three dynasties: Xia, Shang, and Zhou. These dynasties, particularly the Xia, were long thought to be legend; however now the Shang and Zhou are well known archaeologically, and the Xia dynasty has also been established archaeologically. The Xia dynasty existed along the Huang Ho (Yellow) River ca. 2100-1800 BC, and the archaeological site of Erlitou (see map below) has been established as its capital during the latter part of the dynasty. The seventeen rulers recorded for the Xia almost certainly existed, and remains such as as palaces, residential areas, pottery and bronze workshops, and tombs were excavated at Erlitou. The bronze metallurgy was independently developed in China, and not an idea that diffused from western Asia. In all respects Erlitou appears to be the capital of a centralized political state, including the first signs of writing on what are often called oracle bones (see text for photos).

The Shang dynasty followed the Xia, with major centers at An-yang, Ao (under the modern city of Zhengzhou) and Lo-yang.

Map showing Erlitou (Xia dynasty), major sites of Shang dynasty, and Xianyang (Qin Dynasty)

Shang culture is noted for its highly stratified society, as indicated by elaborate tombs for the elite and the planned structure of its cities. Cities each had a ceremonial core, containing royal palaces as well as ancestral temples and meeting houses, surrounded by service areas for specialized crafts in bronze, bone, jade and pottery. Outside the service area were the semi-pit houses of the ordinary people.

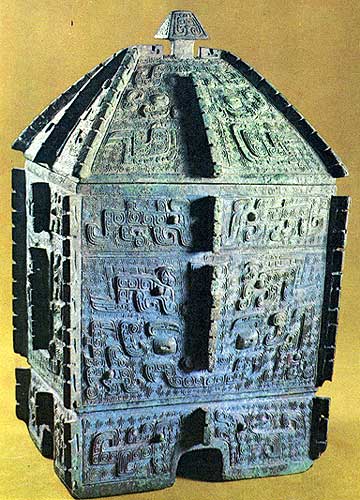

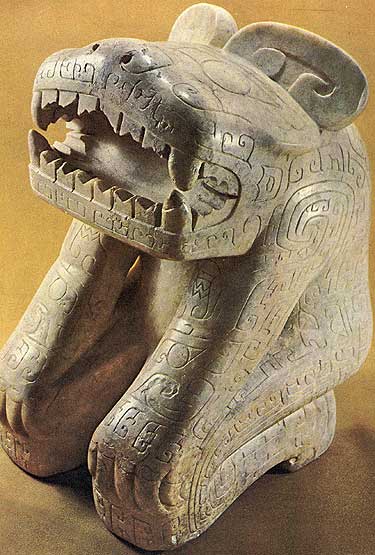

The Shang are known for their expertise with bronze metallurgy, and also with stone, including marble and jade. A few examples are shown below. More can be viewed at the required site of the tomb of Fu Hao, a woman who may have been the consort of a king. Besides reading the first page, be sure to click on both "Bronze objects" and "Jade Objects" for additional pictures.

Bronze Wine Jar (l) and Bronze Pot with Ram's heads (r)

Marble Owl

Marble Tiger, with human traits

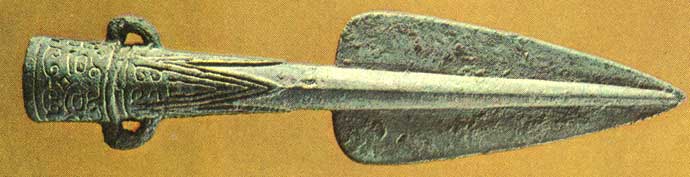

The Shang were also known for their warfare, since there were other emerging states contemporary with them in China, and the Shang appear to have been continually both defending themselves and trying to expand their control. While the favorite weapon was the bow and bronze-tipped arrow, the Shang also had knives, spear heads, and a fearsome 6-in double bladed ax, shown below. (All were hafted on wood or bone shafts or handles.)

Shang Bronze Knife

Shang Spear Point

Shang War-ax Head

The tomb of Fu Hao (see above for required link) with its human sacrifices is pictured below.

Tomb of Fu Hao (her lacquer coffin rested in the discolored area in center)

As the text notes, large tombs of the rulers have also been discovered for the Shang, always with numerous slaves, servants and perhaps other sacrificial victims. Often those who accompanied the dead rulers were beheaded, with the bodies buried in one place, and the heads in another, as below in a burial in a royal tomb at An-yang.

Headless Sacrificial Burials at An-Yang

Royal tombs were huge, and accompanied not only by sacrificial victims but numerous luxury items, including bronze vessels, shell and bone ornaments, jade and marble carvings, and pottery. As noted in the text, royal tombs would have taken thousands of man-hours to build. Commoners in Shang culture were buried in simple graves, usually without any grave goods.

The majority of people remained peasants, whose labor was always need in agriculture, even if they were also conscripted as soldiers, and as laborers for royal tombs and other projects. The plow was not used, and the intensification of agriculture was primarily due to the sheer numbers of people involved. Millet and rice, as well as wheat from western Asia, were the primary crops, and helped support an army of up to 30,000. The pressure on peasant families to produce food made large families a must, since even children could be put to work, and population increased quickly.

Writing also became more important, at least as recorded on bone and shell. Writing may also have been used on silk, bamboo, and wooden tablets, as was the case after 500 BC; if so, none of this survives. Instead, the oracle bones used for divination are found inscribed with questions, and often the answers, using the shoulder blades (scapula) of cattle and water buffalo, as well as turtle shell. By the late Shang times, more than 3,000 symbols were utilized, linked to more recent Chinese writing. Over 150,000 inscribed turtle shells have been found, and these, along with inscriptions on bronze, stone and bone objects, indicate that the subject matter involved the political, military, and ritualistic activities of the upper class. Trade and record keeping for market purposes was usually not involved in these early writings, unlike the early writings of western Asia.