As early as states in Mesopotamia and Egypt, or almost so, was the development of a large and complex state in the valley of the Indus River, in what is now Pakistan. Though Pakistan is now almost entirely a Muslim area, the Indus and what is often termed the Harappan Civilization, are the most likely homeland and partial source for the Hindu religion. Like Mesopotamia and Egypt, the Indus Valley state (ca. 2600-1900 BC) arose from horticultural chiefdoms living in a rich alluvial floodplain. (See also text pp. 454-461) There may have been some diffusion of ideas from Mesopotamia, but much appears to be an indigenous development. Certainly shortly after 4,000 BC the valley was populated by horticulturalists with plow agriculture of wheat and barley, domesticated cattle, sheep and goats, finely painted pottery, copper and bronze metallurgy, and the production of bead jewelry of semi-precious stones. The Indus Valley people may have been the first to domesticate cotton. There is a significant continuity of artifact styles and other organizational features from horticultural chiefdoms to agrarian state. There is also continuity in the system of irrigation canals that developed during the horticultural phases in the Indus Valley.

Unlike early developments in Mesopotamia, the Indus valley appears to have been culturally and economically unified, and possibly may even have been united politically. Also unlike Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley had its own sources of stone, copper, lead and silver, and exported these resources, possibly importing food items from Mesopotamia. Written records in Mesopotamia record that one of their trading partners was a state called Meluhha, which was probably the Indus Valley. Mesopotamia imported ivory, furniture, gold, silver, and semi-precious stones from Meluhha. There are few Mesopotamian artifacts found in the Indus Valley, which indicates the Indus may have imported only perishable items from Mesopotamia.

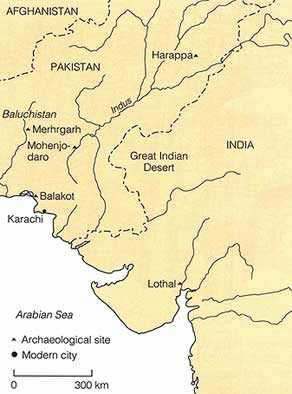

Some 200 large towns or city sites have been recorded associated with the Indus Valley state, and four very large urban centers, of which the best known are Harappa and Mohenjodaro. (And see map in text, p. 454)

Map of Indus Valley, showing the location of the two major, and some minor archaeological sites, as well as the modern city of Karachi. [from Images of the Past, by T.Douglas Price and Gary Feinman, 1993, p.413]

The Indus Valley may be the least well-known of the early political states. There are several reasons for this. First, though there was a written language, it does not appear that the Indus people wrote very much, and most of it has not been deciphered. Most of the writing is on over 4,000 square soapstone seals discovered at various sites, though writing has also been discovered on a few copper tablets and pieces of clay. Though over 400 symbols have been identified, the average text is about five or six symbols. Thus the Indus people have not left us their names, their poems, or even much in the way of their economic records.

Examples of Soapstone Seals, with writing, from the Indus Valley; note particularly on lower right side the figure with a headdress sitting in a lotus position. Some say this is an early representation of the later Hindu deity Shiva, in his role as Lord of the Beasts. [from The Epic of Man, Time Inc., 1961 p.92]

A second reason is that the Harappans did not really produce much in the way of human representational art, the magnificent stone carving of a bearded man on page 458 of your text being one of the rare exceptions. While the culture certainly had class stratification, the distance between the governing elite and the commoners seemed less, materially, than in the early states in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Mediterranean. The ruling class did not lavishly decorate their palaces, temples, or graves with mosaics, paintings, and statutes that depicted their lavish life styles, or their devotion to their gods. In consequence, little is known about the details of those life styles, or the details of their gods. Utilitarian, practical, measured, standardized, all seem words that apply to the early state in the Indus Valley.

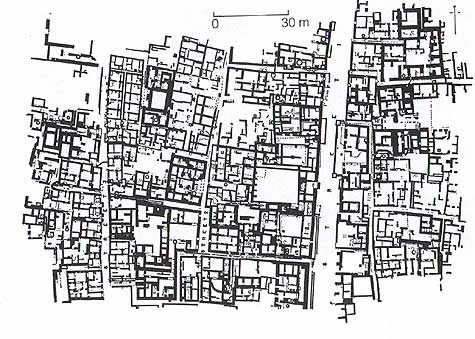

Precise sets of weights and measures have been found archaeologically. Houses appear to have been built to standard dimensions, and the bricks used for building were mostly of a uniform size. Better houses had baked clay bricks, while more modest ones were of sun-dried bricks. Upper class dwellings often had central courtyards, and private showers and toilets connected to a central drainage system which was for the most part built underground. Sanitation appeared to have been important to the people of the Indus Valley.

Excavated Alley, showing the standardized brick construction. The two slits in the building at right are trash chutes, which emptied into bins in the alley. [from The Epic of Man, p.87]

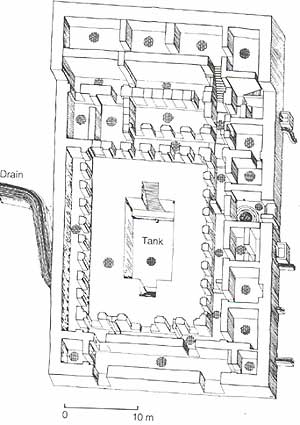

The two urban areas of Mohenjodaro and Harappa almost seem to be planned cities. To view the partially restored ruins of Mohenjodaro, go to http://www.mohenjodaro.net/ and view the brief opening slide show. Then look at several of the slides indexed at the bottom of the page, particularly the ones labeled Citadel and the Great Bath. [Required Site] You certainly don't need to view all the slide sets, but view enough to get some idea of the city. So-called "citadel" areas in both cities were mostly non-residential, public structures which were surrounded by a wall. The Great Bath was about 40 feet by 23 feet, and was 10 feet deep. It may have been a public or a ritual bathing area, with small changing rooms or bathrooms. It was fed by a well, and the bricks were both closely laid and sealed with a type of tar to prevent leaks.

Plan of Great Bath at Mohenjodaro [from Price and Feinman, p. 414]

Plan of Streets and Houses at Mohenjodaro [from Price and Feinman, p. 415]

Excavation of Indus cities reveals craft specialization, with separate living and working quarters occupations like bead makers, coppersmiths, shell makers (pp. 460) and weavers. Some of the smaller communities around the urban areas were devoted to the production of only one craft, like brick making, ceramics or shell-working. Many crafts appear to have been hereditary occupations.

Bronze weapons, fishhooks,an axe-head, knives, and other implements from the Indus Valley [from The Epic of Man, p.87

The Harappans were not all utilitarian and practical however. Jewelry was popular, and of course manufactured beads from semi-precious stones, such as carnelian, jadeite, and agate were, along with gold, an important export. Burials of women often had multiple shell bangles on their left wrist. (see text p. 460-461)

Indus Jewelry [from The Epic of Man, p.89]

In addition, the people of the Indus Valley enjoyed games, and made clever and fanciful toys for their children.

Dice, marbles, balls and a maze (at left); child's toy with a movable head (at right). The dice were marked like modern dice, but had the sides in a different order. [from The Epic of Man, p. 89, 90]

While the Indus Valley continued to be occupied, there was a decline and ultimate abandonment of the urban areas starting shortly after 2000 BC. Various theories have been proposed, though evidence is still inconclusive. Like many of these early states, environmental and social problems, including problems with other invading groups, probably combined. Certainly top-soil erosion, soil depletion, deforestation, and extensive flooding of the river and a possible change in river patterns have been proposed. In addition, as Harappan culture declined, the Indus was invaded by pastoral people from the north who appear to have been much more into warfare than was true of the Harappans, or at least this is one interpretation. This Aryan invasion, and its significance, is discussed in the brief required article The Aryan Migrations. It probably had little to do with the decline of Harappa. (The required article has a good link to more on the myth of the Aryan invasion.)

It was the Harappan culture and some influence with the Aryan culture that probably merged and produced both Hinduism and many attributes associated with Indian culture, such as the caste system. Eventually, the oral traditions of the area composed the Rig Veda, one of three "vedas" or books of poems about the Hindu gods, and first written down between 1300 and 1000 BC. The Rig Veda is thus one of the sacred books of Hinduism.

Without question some of the poems are derived from the oral traditions of the original Indus people, and there is a large amount of continuity from Indus culture. These include ceremonial bathing, specific body positions such as the lotus position, symbolic roles for cattle and elephants, decoration with multiple bangles and necklaces, and almost certainly important aspects of religion.

With the introduction of rice agriculture into the Ganges River Valley on the eastern side of the Indian sub-continent, urban states arose there, and for much of the subsequent history of India were the most important.