There are similarities between Peru and Mesoamerica, but also significant differences. In both, early horticultural villages gave way to larger and larger chiefdoms, culminating in the development of small agrarian states and ultimately empires which united large areas. In Peru there was no core area such as the Valley of Mexico, and power shifted frequently between states in the coastal regions and those in the uplands. Also in Peru, the final empire of the Inca was geographically larger than any in Mesoamerica (or most other parts of the world for that matter) and covered over 380,000 square miles, uniting an area far larger than the Aztecs in Mexico.

Peruvian agriculture included maize, squash, beans, and manioc, but was based more on various types of potato, including sweet potatoes, and the high protein seed of domesticated quinoa, a plant native to the Andes Mountains. Peru also had domesticated the guinea pig, and more importantly the llama and alpaca. Llamas could provide fur, hides, and meat, and could also carry loads of up to 100 lbs., providing Peruvians with a means of goods transport other than humans. In addition, the Peruvians always utilized large quantities of fish from their lengthy Pacific coast, particularly the small anchovy.

Peru never developed the large and efficient trading canoes that plied the coast of Mesoamerica (relying instead on rafts). By Inca times Peru had developed an extensive system of roadways, often paved and with stone or rope suspension bridges, utilized for communication by a system of relay runners as well as for transport. The two main north-south roads ran from Quito, Ecuador in the north to Chile and through Bolivia into Argentina in the south. Like Mesoamerica, Peru had only gold and copper metallurgy, and did not utilize bronze or iron tools, the plow, or the wheel. Unlike Mesoamerica, none of the early states in Peru developed a written language, though the Inca did develop a system of knotted cords, the quipu, for keeping track of numbers. Mesoamerica was more dependent on market exchange, with huge market places such as that at Tenochtitlan, while most Peruvian states had a more powerful stratified redistributive system, with the Inca storing food tributes in large storage areas for eventual use and redistribution.

A chart showing the development of agrarian states along the west coast of South America can be found below, divided into the two main centers, the north coast, and the south-central highlands (extending into the Lake Titicaca basin). All of these areas are covered in the text, though not all will be discussed in this lesson. To see locations of sites and states, check map on p. 393 of your text. The entire chapter 9 in your text should also be read for additional information on all cultures mentioned here.

| Time Period | North Coastal Area | South Central Highlands (incl. Titicaca Basin) |

|---|---|---|

| Late Horizon (1476-1534 AD) | Chimu conquered by Inca ca. 1460 | Inca (to 1534) extend empire into north coastal area and into Ecuador, as well as south to Chile and Argentina |

| Middle Horizon (inc. Early and Late Intermediate)(AD 200-1476) | Chimu State (700-1460 AD) Site: Chan Chan

Moche State (to AD 700) |

Inca establish capital in Cuzco, begin conquering neighbors by 1438 Wari (AD 600-850) Tiwanaku (AD 450-AD 1200) in Titicaca Basin Nasca State (1 AD to 750 AD) (southern coast) |

| Early Horizon (900 BC-AD 200) | Moche State (200BC-AD 700) Site: Sipan | Chavin State 900 BC-200 BC Site: Chavin de Huantar |

Pre-Early Horizon (ca. 1800-900 BC |

Early Horticultural Chiefdoms |

Site of Chavin de Huantar occupied ca. 1500 BC (central highlands) Early Horticultural Chiefdoms throughout area |

In some respects, Chavin was the "mother culture" of subsequent Peruvian states in the same way that the Olmec may have been in Mesoamerica. Developing out of complex chiefdoms, the Chavin started to develop monumental architecture as early as 1000BC, including ceremonial mounds and pyramids, often built in a U shape around large plazas. The best known site associated with Chavin is that of Chavin de Huantar, which was primarily a ceremonial center located in the northern part of the central highlands some 10,000 feet above sea level. After 900 BC, at least several thousand people lived at the site in residential areas surrounding the main ceremonial center. Chavin contributed art and architectural styles and perhaps religious and ideological conventions throughout a wide area, and established exchange and communication between highland and coastal settlements. Element that Chavin may have helped contribute to later states include the following.

To gain some appreciation for the site of Chavin de Huantar, click here and view the pictures and even a video (not required, and read pp. 400-403 in your text, which is required.)

Moche is both the name of a small state and of its principal site, located in the Moche River Valley on the northern coast of Peru. In its time, this was the largest city (though small) of its time, and the Moche controlled neighboring river valleys as well as their. own. Moche culture was highly stratified and militaristic. The site of Moche appears to have been primarily a ceremonial center, with two large pyramid or platform structures (one is 130 feet tall, and measures 1100 by 525 feet at the base), both made of hundreds of millions of adobe brick, most with their maker's mark on the individual brick.

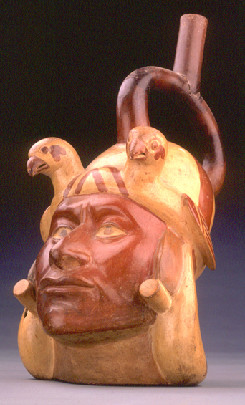

Moche culture is perhaps best known for some of its crafts, particularly in gold, copper and silver. [The cover of your text depicts a Moche gold pendant, and your text contains an excellent discussion of Moche metal working skills.] However the pottery of the Moche was in a class by itself; indeed, I am not sure the world has seen anything like it before or since. Moche potters used pottery forms, paint, and high relief sculptures to leave a record of mythical, ritual, and everyday life that could hardly be improved upon with a written record. Everything is recorded: fishermen at sea in one-man canoes made of bundles of rushes, farmers, warriors, weavers, prisoners, rulers carried in litters, mothers and children are all depicted in and on pots. There are scenes of naked prisoners being led with ropes around their necks, throats are slit, and there is ritual drinking of human blood, along with scenes of defleshed human bones being hung on ropes. Archaeologists in the past wondered if the scenes were too horrible to be really true, until more recent excavation of burials between the two main platforms at Moche found ample skeletal evidence that this was exactly the fate of many Moche captives.

Moche Stirrup Pot, Showing Warrior Portrait [Wikimedia Commons]

In addition, Moche pottery sometimes explicitly showed various human sexual practices, from heterosexual intercourse to homosexual intercourse to masturbation to fellatio to sodomy. At one time much of this pottery was considered too "pornographic" by modern cultures in North and South America to be freely exhibited to the public in museums. However to see three of the milder sexually explicit pots, click here. (Be warned; don't click if you don't want to.) To see a few (43, actually) additional photos of Moche pots--only a couple of which are mildly pornographic--click here; more about the Moche generally, click here.)

The Moche also left behind burials at the site of Sipan, which where discovered undisturbed in the 1980's. Be sure to note the account in your text (pp. 411-414), and also click here and scroll down the page to see some of the artifacts in color. (Required site)

One of the smaller states that arose on the southern coast of Peru was the Nasca, (sometimes spelled Nazca). At most controlling two of the river valleys in what was otherwise an extremely arid coastal region, the Nasca continued traditions from earlier and related kingdoms in crafts, particularly pottery and textiles. Their pottery, like the Moche, consisted of polychrome pots, but with much brighter polychrome colors, and a more light-hearted approach to some of their themes. Animals, including those in the ocean, were a favorite theme, as shown below.

Fanciful Killer Whale (?) Pot of the Nasca [Wikimedia Commons]

To see more Nasca pottery, click here, and scroll down to the pictures of pots.

The Nasca are best known for the Nasca lines (technically geoglyphs) found in the nearby desert landscape (see text p. 410). Spread over an area of a few hundred square miles, the lines were made by removing dark rock on the desert surface and exposing a light-colored soil that is underneath. Depicted are various geometric shapes, as well as animals such as birds, lizards and fish, with one spider and one monkey. A few are humanlike. The lines can best be seen from an airplane a few hundred feet in the air; however many have pointed out that the lines are quite visible from the ground, and entire figures can be seen from nearby low mounds or hills.

Nasca Monkey, with other lines [Public Domain]

There are many hypotheses as to the purpose of the lines. Some assume the Nasca had sky gods, and the lines were made so that they could easily be seen by the gods. Others point out that some lines are connected or point the way to water sources in the ground, while other hypotheses relate to astronomy. One anthropologist has noted that traditional culture in the area included traveling to designated spots and leaving offerings, and interprets the lines as signposts along the way. There is indeed some archaeological evidence that the lines were in fact walked by the Nasca. Of course, the lines have also been declared to have been made by ancient, and alien, astronauts, for which certainly there is no evidence. (This last one to me seems to be an extreme extension of the mind-set that says Europeans must have built the Hopewell burial mounds, or that Egyptians must have made the Olmec pyramids, or the Inca constructed the Easter Island statues--since the local folk could not have possessed the skill and intelligence to do so. ) To see more of the lines, and if you want, to read about research on the lines and the efforts to preserve them, click here.

The Chimu and Inca were the two late states in Peru, both of which, but particularly the Inca, deserved the name empire. The Chimu were a northern coastal people, who solidified the control of twelve river valleys by 700 AD, including the Moche Valley.(see map on p. 419 of text) The Chimu extended the elaborate irrigation canals in northern Peru, and established the adobe-brick city of Chan Chan at the mouth of the Moche Valley. The city covered some as much as seven square miles, with a four mile square center that included nine huge walled compounds, each probably belonging to a ruler of the Chimu. The Chimu probably developed the institution of "split inheritance" mentioned in your text (p 420). In 1460 the Chimu were conquered by the Inca (who probably cut off the water sources to the canals).

Ruins of Walls from an Enclosure at Chan Chan [Public Domain]

The Inca are perhaps the best know, and shortest lived, of the Peruvian agrarian states, though they were both the first to control all of Peru and to extend control north into Ecuador and south into Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina. (see map on p. 423 of the text) In the highland areas of the Andes, the Inca established an elaborate system of terraces for the cultivation of crops, and had more of the scarce arable land under cultivation than is true today. As was the case for most of the earlier Peruvian states, they raised maize, quinoa, potatoes, beans and squash, among other crops. The llama remained an important domesticate for transportation and fur, and the guinea pig was domesticated for meat.

Inca Agricultural Terraces in Andes Mountains [Public Domain]

Your text has an excellent description of the Inca, and their capital city of Cuzco (located at an elevation of 11,800 feet). Cuzco was always more an administrative center than a large city on the order of Tenochtitlan, and the market area of the city was small and found outside the city center. The conquering Spaniards under Francisco Pizarro were able to use the already mentioned Inca road system (see text p. 427) to quickly move south after their landing on the north coast of Peru in 1532, though again smallpox preceded their arrival in Cuzco. In an almost unrivaled story of greed and treachery (with the help of disease), the handful of Spaniards were able to destroy the Inca Empire by 1534 AD. [Click here, not required, for a PBS site of Pizarro's conquest of Peru.]

Inca Fortress, illustrating their Cut Stone Walls [Public Domain]