Fundamental Causes of Cultural Change

Cultural materialism, as already noted, is a diachronic theory, looking at cultures through time. As such, it can contribute to an understanding of the reasons for cultural change. What I am going to present here is a model to at least partially explain some types of cultural change. It is helpful, but clearly not complete. (Your text refers to this model, and to cultural materialism generally, as the evolutionary-ecological model.See Chapter 5)

Modern foragers tend to have a population growth rate of close to zero. This means that on the average every couple raises two children to adulthood, thus replacing themselves. In looking at human population growth, human groups are certainly biologically capable of having more children. The number of children the average human male could produce is limited only by the number of fertile females to which he has access. Hence the real limitation to human population growth is related to the number of females in the society.

Sixteen babies: a number a normal woman under optimum conditions could have and raise to adulthood.

On average, women are fertile between the ages of 15 and 45; under optimal conditions, a woman could have between 20-25 life births during those years. Some 15-16 children (the number shown above) could be raised to adulthood. In reality few cultures have this type of birth rate; the Hutterites (a religious group in the United States and Canada) may hold the recent record of an average of 9 births per woman. However, anything over 2 births per woman will cause the population to expand, and in most cultures in the past women had more than two offspring. It is this expansion of population which creates population pressure on a culture and its resources. An increase in population, no matter what the mode of production, is likely to pose a threat to resources. Even if population is not actually increasing, the pressure may be felt if standards of living are low and the methods that restrain population growth are themselves costly (abortion, infanticide, high infant mortality rate).

When faced with population pressure, particularly as population expands to pose a threat to the standard of living, a culture and the individuals within it have essentially four "choices" or options. A culture does not usually articulate these choices, nor are most people within the culture necessarily conscious of these choices.

Migration

When a culture faces a declining standard of living due to population pressure, the first option is migration. This scenario is almost certainly the reason the entire world was populated after modern Homo sapiens appeared in Africa some 200,000 years ago. As population grew, the carrying capacity of the land under a foraging mode of production was quickly reached. (Carrying capacity with regard to human cultures is best thought of as the maximum population that a habitat can sustain, under a specific mode of production.) Once the carrying capacity of a specific area was reached, foraging bands split and migrated into new areas in order to find the food necessary to sustain the band. Expanding population however, once again created a threat to the standard of living, and resulted in the need for more migration. This process was repeated and repeated until by 10,000 years ago almost the entire habitable world (with the exception of the Pacific Islands) was occupied by foragers. When there is a threat to the standard of living (what ever that standard may be) the most popular option has always been migration, regardless of the mode of production. As the world became increasingly crowded, and people were surrounded by other cultures, that option became less viable. At the individual and family level however, migration is still popular when faced with threats to living standards.

Intensification

A second option is intensification of production, which means the members of a culture work longer and harder. Intensification is another way to produce more calories to feed a growing population. If we look at a foraging culture, they could obtain more food, at least temporarily, by working longer and harder. Instead of working a mere 20 hours per week on the average, they could hunt and gather for 30 or 40 hours per week. This would enable them to support more people at their present standard of living. However, it is also clear that in the long run, plants and animals in the vicinity would be depleted. As the environment is depleted, there is a threat to the standard of living, forcing the culture back to its original problem.

Technological Improvement

A third option is to improve the technology of production so that it is more efficient. Foragers such as the San could presumably obtain more food from their environment if they made better bows and arrows. If they made bigger bows, and larger arrows, their arrows would penetrate more deeply, and kill more quickly. In this way they would lose a smaller percentage of their game to scavengers who reach the dying animal before the hunters do. Larger, stronger bows would also mean that the arrows would travel farther, and that the hunters would not have to get so close to the animal to hit it. As a result, fewer animals would notice the hunters and run away. All of this would result in more calories to support more people. In the long run however, such efficient hunting techniques would deplete the environment, and cause a new threat to the standard of living. Regardless of how much foragers improve their technology, the end result will be environmental depletion, which threatens their standard of living, and leaves them with the same four options.

Control Population Growth

The fourth option, and the least popular, is to control population growth. For foragers, the major way to control population growth was by abstinence: sexual intercourse was often forbidden during the lengthy period the child was nursing, and sometimes for other reasons. Even lengthy nursing alone, combined with the San's low fat diet and active life style, tended to suppress ovulation. As a result, births were often spaced four to five years apart in foragers like the San, and in combination with a high infant mortality rate, resulted in zero population growth. Hence the San were able to survive in a limited geographical area for generations, with adequate nutrition. Etically, one could say that the spacing of San children, plus the natural high infant mortality rates, were adaptations to the environment. Emically, San women would tell you that they preferred to have their children at least four years apart, since it was so difficult to carry more than one young child when they went gathering or when the camp had to be moved. Regardless of why San women were spacing their children, the effect was adaptive: population did not rise to pose a threat to standard of living.

The same scenario of culture change is present in horticultural and all other modes of production. Before safe and reliable methods of birth control and abortion, controlling the birth rate by any other method than abstinence was costly, and often no more popular than abstinence. It was not until the industrial mode of production and the invention of the rubber condom in the 19th century that a safe and reliable method of birth control was possible, and not until the 20th century that safe methods of abortion were developed. Until that time, controlling population growth was difficult, to say the least, for any culture. In addition, in many modes of production, as we will see, there was a great economic benefit to having many children, which pushed up the birth rate.

A Model of Cultural Change

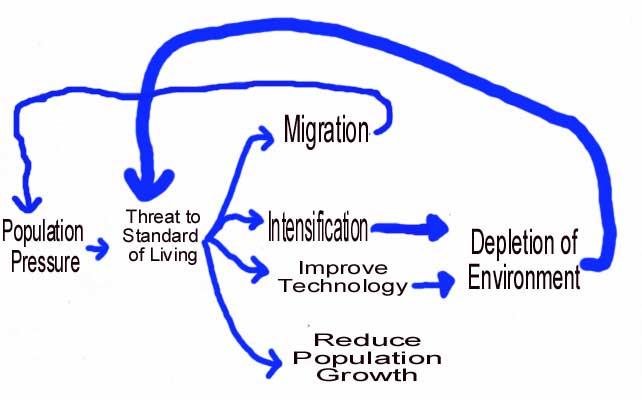

As the graph below indicates, all of this is a model for cultural change. As population grows, there is a threat to the standard of living. One solution to the problem is for part of the culture to migrate somewhere else. This temporarily solves the problem, but as population grows in the new location, population pressure once again poses a threat to the standard of living.

A Model of Cultural Change

Another solution is to intensify production, i.e. to convince people to work longer and harder. This will allow more food to be produced, and will temporarily relieve any threat to standard of living. However, intensification will lead to environmental depletion, which itself poses a threat to the standard of living. Improving technology will in the long run have the same effect, posing a threat to the standard of living and leaving the culture back with its same four choices. If portions of the culture can migrate, they probably will, but as the world became more and more populated, this became less and less of a viable option. Foragers in many areas continued to improve technology (as the archaeological record shows) and no doubt also intensified production in repeated cycles in response to a threat to standard of living. Eventually, if the environment made such a change possible, they were forced to develop a new mode of production, horticulture. Horticulture does represent an intensification, for horticulturists work longer and harder than foragers. Horticulture also represented a much more productive technology, able to extract many more calories per unit area of land than was true of foraging. The price paid for these additional calories and the ability to support larger populations, was explored in "The Worst Mistake" article. But horticulture did not get humanity out of the above cycle, as we will see in the next unit. Expanding populations created population pressure and a threat to the standard of living, and horticulturists were faced with the same four choices.

|