|

Eating Christmas in the KalahariRichard Lee

“Eating Christmas in the Kalahari” by Richard Borshay Lee was published in the December 1969 issue of Natural History. It is one of the magazine’s most frequently reprinted stories. In the final paragraph, Lee wondered what the future would hold for the !Kung Bushmen with whom he had shared a memorable Christmas feast. The University of Toronto anthropologist answers that question for the Botswana San, in a 2000 postscript to his original article. (The postscript follows the main story). A more recent update will be found in Unit 3. The "Bushmen" are more properly referred to as San in anthropology, and refer to themselves as Ju/’hoansi. The San will also be our example of a foraging mode of production, since that is what they were when Lee began his study in the late 1960's. Lee studied the San in Botswana, although they are also found in Namibia, living in one of the most difficult environments, the Kalahari Desert. Foraging will be discussed later in Unit 1, and you will read more about the San. Editor’s Note: The !Kung and other Bushmen speak click languages. In the story, three different clicks are used:

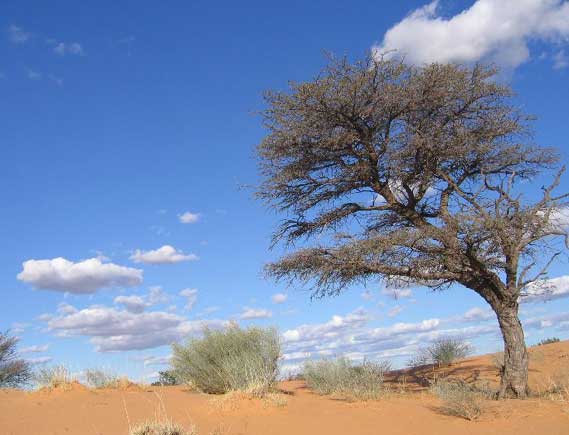

The Kalahari, Home of the San The !Kung Bushmen’s knowledge of Christmas is thirdhand. The London Missionary Society brought the holiday to the southern Tswana tribes in the early nineteenth century. Later, native catechists spread the idea far and wide among the Bantu-speaking pastoralists, even in the remotest corners of the Kalahari Desert. The Bushmen’s idea of the Christmas story, stripped to its essentials, is “praise the birth of white man’s god-chief”; what keeps their interest in the holiday high is the Tswana-Herero custom of slaughtering an ox for his Bushmen neighbors as an annual goodwill gesture. Since the 1930’s, part of the Bushmen’s annual round of activities has included a December congregation at the cattle posts for trading, marriage brokering, and several days of trance-dance feasting at which the local Tswana headman is host. As a social anthropologist working with !Kung Bushmen, I found that the Christmas ox custom suited my purposes. I had come to the Kalahari to study the hunting and gathering subsistence economy of the !Kung, and to accomplish this it was essential not to provide them with food, share my own food, or interfere in any way with their food-gathering activities. While liberal handouts of tobacco and medical supplies were appreciated, they were scarcely adequate to erase the glaring disparity in wealth between the anthropologist, who maintained a two-month inventory of canned goods, and the Bushmen, who rarely had a day’s supply of food on hand. My approach, while paying off in terms of data, left me open to frequent accusations of stinginess and hard-heartedness. By their lights, I was a miser. The Christmas ox was to be my way of saying thank you for the co-operation of the past year; and since it was to be our last Christmas in the field, I determined to slaughter the largest, meatiest ox that money could buy, insuring that the feast and trance dance would be a success. Through December I kept my eyes open at the wells as the cattle were brought down for watering. Several animals were offered, but none had quite the grossness that I had in mind. Then, ten days before the holiday, a Herero friend led an ox of astonishing size and mass up to our camp. It was solid black, stood five feet high at the shoulder, had a five-foot span of horns, and must have weighed 1,200 pounds on the hoof. Food consumption calculations are my specialty, and I quickly figured that bones and viscera aside, there was enough meat—at least four pounds—for every man, woman, and child of the 150 Bushmen in the vicinity of the /Xai/xai who were expected at the feast. Having found the right animal at last, I paid the Herero £20 ($56) and asked him to keep the beast with his herd until Christmas day. The next morning word spread among the people that the big solid black one was the ox chosen by /ontah (my Bushman name; it means, roughly, “whitey”) for the Christmas feast. That afternoon I received the first delegation. Ben!a, an outspoken sixty-year-old mother of five, came to the point slowly. “Where were you planning to eat Christmas?” “Right here at /Xai/xai,” I replied. “Alone or with others?” “I expect to invite all the people to eat Christmas with me. “Eat what?” “I have purchased Yehave’s black ox, and I am going to slaughter and cook it.” “That’s what we were told at the well but refused to believe it until we heard it from yourself.” “Well, it’s the black one,” I replied expansively, although wondering what she was driving at. “Oh, no!” Ben!a groaned, turning to her group. “They were right.” Turning back to me she asked, “Do you expect us to eat that bag of bones?” “Bag of bones! It’s the biggest ox at /Xai/xai.” “Big, yes, but old. And thin. Everybody knows there’s no meat on that old ox. What did you expect us to eat off it, the horns?” Everybody chuckled at Ben!a’s one-liner as they walked away, but all I could manage was a weak grin. That evening it was the turn of the young men. They came to sit at our evening fire. /gaugo, about my age, spoke to me man-to-man. “/ontah, you have always been square with us,” he lied. “What has happened to change your heart? That sack of guts and bones of Yehave’s will hardly feed one camp, let alone all the Bushmen around /Xai/xai.” And he proceeded to enumerate the seven camps in the /Xai/xai vicinity, family by family. “Perhaps you have forgotten that we are not few, but many. Or are you too blind to tell the difference between a proper cow and an old wreck? That ox is thin to the point of death.” “Look, you guys,” I retorted, “that is a beautiful animal, and I’m sure you will eat it with pleasure at Christmas.” “Of course we will eat it; it’s food. But it won’t fill us up to the point where we will have enough strength to dance. We will eat and go home to bed with stomachs rumbling.” That night as we turned in, I asked my wife, Nancy: “What did you think of the black ox?” “It looked enormous to me. Why?” “Well, about eight different people have told me I got gypped; that the ox is nothing but bones.” “What’s the angle?” Nancy asked. “Did they have a better one to sell?” “No, they just said that it was going to be a grim Christmas because there won’t be enough meat to go around. Maybe I’ll get an independent judge to look at the beast in the morning.” Bright and early, Halingisi, a Tswana cattle owner, appeared at our camp. But before I could ask him to give me his opinion on Yehave’s black ox, he gave me the eye signal that indicated a confidential chat. We left the camp and sat down. “/ontah, I’m surprised at you; you’ve lived here for three years and still haven’t learned anything about cattle.” “But what else can a person do but choose the biggest, strongest animal one can find?” I retorted. “Look, just because an animal is big doesn’t mean that it has plenty of meat on it. The black one was a beauty when it was younger, but now it is thin to the point of death.” “Well I’ve already bought it. What can I do at this stage?” “Bought it already? I thought you were just considering it. Well, you’ll have to kill it and serve it, I suppose. But don’t expect much of a dance to follow.” My spirits dropped rapidly. I could believe that Ben!a and /gaugo just might be putting me on about the black ox, but Halingisi seemed to be an impartial critic. I went around that day feeling as though I had bought a lemon of a used car. “My friend, the way it is with us Bushmen,” he began, “is that we love meat. And even more than that, we love fat.” In the afternoon it was Tomazo’s turn. Tomazo is a fine hunter, a top trance performer, and one of my most reliable informants. He approached the subject of the Christmas cow as part of my continuing Bushmen education. “My friend, the way it is with us Bushmen,” he began, “is that we love meat. And even more than that, we love fat. When we hunt we always search for the fat ones, the ones dripping with layers of white fat: fat that turns into a clear, thick oil in the cooking pot, fat that slides down your gullet, fills your stomach and gives you a roaring diarrhea,” he rhapsodized. “So, feeling as we do,” he continued, “it gives us pain to be served such a scrawny thing as Yehave’s black ox. It is big, yes, and no doubt its giant bones are good for soup, but fat is what we really crave and so we will eat Christmas this year with a heavy heart.” The prospect of a gloomy Christmas now had me worried, so I asked Tomazo what I could do about it. “Look for a fat one, a young one . . . smaller, but fat. Fat enough to make us //gom (‘evacuate the bowels’), then we will be happy.” My suspicions were aroused when Tomazo said that he happened to know of a young, fat, barren cow that the owner was willing to part with. Was Toma working on commission, I wondered? But I dispelled this unworthy thought when we approached the Herero owner of the cow in question and found that he had decided not to sell. The scrawny wreck of a Christmas ox now became the talk of the /Xai/xai water hole and was the first news told to the outlying groups as they began to come in from the bush for the feast. What finally convinced me that real trouble might be brewing was the visit from u!lau, an old conservative with a reputation for fierceness. His nickname meant spear and referred to an incident thirty years ago in which he had speared a man to death. He had an intense manner; fixing me with his eyes, he said in clipped tones: “I have only just heard about the black ox today, or else I would have come here earlier. /ontah, do you honestly think you can serve meat like that to people and avoid a fight?” He paused, letting the implications sink in. “I don’t mean fight you, /ontah; you are a white man. I mean a fight between Bushmen. There are many fierce ones here, and with such a small quantity of meat to distribute, how can you give everybody a fair share? Someone is sure to accuse another of taking too much or hogging all the choice pieces. Then you will see what happens when some go hungry while others eat.” The possibility of at least a serious argument struck me as all too real. I had witnessed the tension that surrounds the distribution of meat from a kudu or gemsbok kill, and had documented many arguments that sprang up from a real or imagined slight in meat distribution. The owners of a kill may spend up to two hours arranging and rearranging the piles of meat under the gaze of a circle of recipients before handing them out. And I also knew that the Christmas feast at /Xai/xai would be bringing together groups that had feuded in the past. Convinced now of the gravity of the situation, I went in earnest to search for a second cow; but all my inquiries failed to turn one up. The Christmas feast was evidently going to be a disaster, and the incessant complaints about the meagerness of the ox had already taken the fun out of it for me. Moreover, I was getting bored with the wisecracks, and after losing my temper a few times, I resolved to serve the beast anyway. If the meat fell short, the hell with it. In the Bushmen idiom, I announced to all who would listen: “I am a poor man and blind. If I have chosen one that is too old and too thin, we will eat it anyway and see if there is enough meat there to quiet the rumbling of our stomachs.” On hearing this speech, Ben!a offered me a rare word of comfort. “It’s thin,” she said philosophically, “but the bones will make a good soup.” At dawn Christmas morning, instinct told me to turn over the butchering and cooking to a friend and take off with Nancy to spend Christmas alone in the bush. But curiosity kept me from retreating. I wanted to see what such a scrawny ox looked like on butchering, and if there was going to be a fight, I wanted to catch every word of it. Anthropologists are incurable that way. The great beast was driven up to our dancing ground, and a shot in the forehead dropped it in its tracks. Then, freshly cut branches were heaped around the fallen carcass to receive the meat. Ten men volunteered to help with the cutting. I asked /gaugo to make the breast bone cut. This cut, which begins the butchering process for most large game, offers easy access for removal of the viscera. But it also allows the hunter to spot-check the amount of fat on the animal. A fat game animal carries a white layer up to an inch thick on the chest, while in a thin one, the knife will quickly cut to bone. All eyes fixed on his hand as /gaugo, dwarfed by the great carcass, knelt to the breast. The first cut opened a pool of solid white in the black skin. The second and third cut widened and deepened the creamy white. Still no bone. It was pure fat; it must have been two inches thick. “Hey /gau,” I burst out, “that ox is loaded with fat. What’s this about the ox being too thin to bother eating? Are you out of your mind?” “Fat?” /gau shot back, “You call that fat? This wreck is thin, sick, dead!” And he broke out laughing. So did everyone else. They rolled on the ground, paralyzed with laughter. Everybody laughed except me; I was thinking. I ran back to the tent and burst in just as Nancy was getting up. “Hey, the black ox. It’s fat as hell! They were kidding about it being too thin to eat. It was a joke or something. A put-on. Everyone is really delighted with it!” “Some joke,” my wife replied. “It was so funny that you were ready to pack up and leave /Xai/xai.” If it had indeed been a joke, it had been an extraordinarily convincing one, and tinged, I thought, with more than a touch of malice as many jokes are. Nevertheless, that it was a joke lifted my spirits considerably, and I returned to the butchering site where the shape of the ox was rapidly disappearing under the axes and knives of the butchers. The atmosphere had become festive. Grinning broadly, their arms covered with blood well past the elbow, men packed chunks of meat into the big cast-iron cooking pots, fifty pounds to the load, and muttered and chuckled all the while about the thinness and worthlessness of the animal and /ontah’s poor judgment. We danced and ate that ox two days and two nights; we cooked and distributed fourteen potfuls of meat and no one went home hungry and no fights broke out. But the “joke” stayed in my mind. I had a growing feeling that something important had happened in my relationship with the Bushmen and that the clue lay in the meaning of the joke. Several days later, when most of the people had dispersed back to the bush camps, I raised the question with Hakekgose, a Tswana man who had grown up among the !Kung, married a !Kung girl, and who probably knew their culture better than any other non-Bushmen. “With us whites,” I began, “Christmas is supposed to be the day of friendship and brotherly love. What I can’t figure out is why the Bushmen went to such lengths to criticize and belittle the ox I had bought for the feast. The animal was perfectly good and their jokes and wisecracks practically ruined the holiday for me.” “So it really did bother you,” said Hakekgose. “Well, that’s the way they always talk. When I take my rifle and go hunting with them, if I miss, they laugh at me for the rest of the day. But even if I hit and bring one down, it’s no better. To them, the kill is always too small or too old or too thin; and as we sit down on the kill site to cook and eat the liver, they keep grumbling, even with their mouths full of meat. They say things like, ‘Oh, this is awful! What a worthless animal! Whatever made me think that this Tswana rascal could hunt!’” “Is this the way outsiders are treated?” I asked. “No, it is their custom; they talk that way to each other too. Go and ask them.” /gaugo had been one of the most enthusiastic in making me feel bad about the merit of the Christmas ox. I sought him out first. “Why did you tell me the black ox was worthless, when you could see that it was loaded with fat and meat?” “It is our way,” he said smiling. “We always like to fool people about that. Say there is a Bushman who has been hunting. He must not come home and announce like a braggard, ‘I have killed a big one in the bush!’ He must first sit down in silence until I or someone else comes up to his fire and asks, ‘What did you see today?’ He replies quietly, ‘Ah, I’m no good for hunting. I saw nothing at all [pause] just a little tiny one.’ Then I smile to myself,” /gaugo continued, “because I know he has killed something big.” In the morning we make up a party of four or five people to cut up and carry the meat back to the camp. When we arrive at the kill we examine it and cry out, ‘You mean to say you have dragged us all the way out here in order to make us cart home your pile of bones? Oh, if I had know it was this thin I wouldn’t have come.’ Another one pipes up, ‘People, to think I gave up a nice day in the shade for this. At home we may be hungry but at least we have nice cool water to drink.’ If the horns are big, someone says, ’Did you think that somehow you were going to boil down the horns for soup?’ “To all this you must respond in kind. ‘I agree,’” you say, ’this one is not worth the effort; let’s just cook the liver for strength and leave the rest for the hyenas. It is not too late to hunt today and even a duiker or a steenbok would be better than this mess.’” “Then you set to work nevertheless; butcher the animal, carry the meat back to the camp and everyone eats,” /gaugo concluded. “But,” I asked, “why insult a man after he has gone to all that trouble to track and kill an animal and when he is going to share the meat with you so that your children will have something to eat?” Things were beginning to make sense. Next, I went to Tomazo. He corroborated /gaugo’s story of the obligatory insults over a kill and added a few details of his own. “But,” I asked, “why insult a man after he has gone to all that trouble to track and kill an animal and when he is going to share the meat with you so that your children will have something to eat?” “Arrogance,” was his cryptic answer. “Arrogance?” “Yes, when a young man kills much meat he comes to think of himself as a chief or a big man, and he thinks of the rest of us as his servants or inferiors. We can’t accept this. We refuse one who boasts, for someday his pride will make him kill somebody. So we always speak of his meat as worthless. This way we cool his heart and make him gentle.” “But why didn’t you tell me this before?” I asked Tomazo with some heat. “Because you never asked me,” said Tomazo, echoing the refrain that has come to haunt every field ethnographer. I had been taught an object lesson by the Bushmen; it had come from an unexpected corner and had hurt me in a vulnerable area. The pieces now fell into place. I had known for a long time that in situations of social conflict with Bushmen I held all the cards. I was the only source of tobacco in a thousand square miles, and I was not incapable of cutting an individual off for noncooperation. Though my boycott never lasted longer than a few days, it was an indication of my strength. People resented my presence at the water hole, yet simultaneously dreaded my leaving. In short I was a perfect target for the charge of arrogance and for the Bushmen tactic of enforcing humility. I had been taught an object lesson by the Bushmen; it had come from an unexpected corner and had hurt me in a vulnerable area. For the big black ox was to be the one totally generous, unstinting act of my year at /Xai/xai, and I was quite unprepared for the reaction I received. As I read it, their message was this: There are no totally generous acts. All “acts” have an element of calculation. One black ox slaughtered at Christmas does not wipe out a year of careful manipulation of gifts given to serve your own ends. After all, to kill an animal and share the meat with people is really no more than Bushmen do for each other every day and with far less fanfare. In the end, I had to admire how the Bushmen had played out the farce-collectively straight-faced to the end. Curiously, the episode reminded me of the Good Soldier Schweik and his marvelous encounters with authority. Like Schweik, the Bushmen had retained a thoroughgoing skepticism of good intentions. Was it this independence of spirit, I wondered, that had kept them culturally viable in the face of generations of contact with more powerful societies, both black and white? The thought that the Bushmen were alive and well in the Kalahari was strangely comforting. Perhaps, armed with that independence and with their superb knowledge of their environment, they might yet survive the future. People of /Xai/xai Thirty Years On (2000)Had the !Kung’s unique mix of knowledge of their environment, strong family ties, and healthy skepticism of outsiders enabled them to survive the future as I predicted three decades ago? I returned to /Xai/xai in July 1999 to find out. I had made occasional trips to the area over the years but this was my first visit in more than a decade. One of the major changes that antedated my return was the change in naming. The !Kung name for themselves is Ju/’hoansi, meaning “real” or “genuine people.” As they have come to political consciousness, they have urged their neighbors, government officials, and visitors to call them by their rightful name, and this has been widely adopted. A second change is the replacement of the term “Bushmen” with “San,” a Khoi word meaning “aborigines” or “settlers proper.” This too has come into wide currency. As I approached /Xai/xai after the long and still grueling trip in a four-wheel drive vehicle over the Aha Hills, I noted the major developments in the village. A school built in the mid-seventies had been expanded and now accommodated more than 70 pupils. Nearby stood the clinic with its resident nurse, ministering to the needs of a population now grown to over 300 from 150 in 1969. A borehole well with its diesel pump and water tower served the entire community; the hand-dug wells had fallen into disuse. But in other ways the village had not changed much. It was still dusty and drowsy in the midday sun, with people dispersed at their hamlets spread out over a mile of bush and savannah ringing the watering hole. Until the 1960s, the people had lived in the beehive-shaped grass huts characteristic of the Kalahari San. Now most have built semi-permanent mud-walled structures to house the larger families that have resulted from a significant settling-down process begun twenty years ago. Hunting and gathering now provides only a fraction of the village’s food supplies, though a significant one. Two-thirds of the diet comes from farmed fields, cash purchases and drought relief and only one third from foraging. Part of the cash—earned from wage work and the sale of crafts—goes to generate a steady supply of home-brew beer, which has made for many convivial evenings and a number of problem drinkers. Through the 1970s and ’80s, the Ju/’hoansi built up small herds of cattle, but an outbreak of bovine pleuropneumonia in 1995 forced the government to destroy the entire cattle population of the district. Along with their neighbors, the Ju received cash compensation but have been slow to reinvest in cattle. Over the years employment in the cash economy had ebbed and flowed. For a long time the Botswana Geological Survey had maintained a large camp for prospecters of the rich diamond pipes which are so common in the Kalahari and which have fueled Botswana’s booming economy. Even though the diamond finds did not materialize, the /Xai/xai Ju/’hoansi have looked on work opportunities in the cash economy as an attractive alternative to subsistence farming. These experiences no doubt played a role in the people of /Xai/xai embarking on a new path. In 1998 they set up the Tabololo Development Trust, a grass-roots organization dedicated to wildlife management and the preservation of the environment. Similar village-level organizations are springing up in many parts of southern and eastern Africa. The Trust offers ecotourism: visitors can go bird-watching, take photographs, and see Ju/’hoansi perform dances and demonstrate crafts; visitors also can go on limited hunting safaris. The younger members of the community point with quiet pride to the roughly $15,000 earned by the Trust in its first year of operation. But not everyone in the community is thrilled by the new development. Some of the young dancers present at the slaughter of the ox that I wrote about in 1969 are now elders, and for them, turning over the village’s natural resources to the Trust is a breach of the common property regime that had prevailed for time beyond time. Formerly, foragers would go out to hunt and gather and noone would question their right to do so. Now they complain that the members of the Trust staff scrutinize everyone’s catch to ensure that no one is hunting or gathering out of season. It will take a while for the overzealous youth and the resentful elders to find a middle ground. To my mind, one of the best indices of whether the Ju/’hoansi were truly “alive and well” was the famous medicine dance, or n/um tchai. It was chronicled in Healing Makes Our Hearts Happy: Spirituality & Cultural Transformation Among the Kalahari Ju’Hoansi, a book by Richard Katz, Megan Biesele, and Verna St. Denis, (Inner Traditions International, 1997), and in Nyae Nyae !Kung: Beliefs and Rites (Peabody Museum Press, 1999), by Lorna Marshall, the dean of Kalahari ethnographers, now in her 103rd year. Although most of the great healers alive at the 1969 Christmas feast are long gone, a new generation of men and women in their thirties and forties have taken up the work and continue to provide spiritual protection to the community through the healing power of their n/um. Despite the many changes they had experienced, I came away from my revisit with the feeling that the stewardship of the Ju/’hoansi of /Xai/xai remained in good hands. |