|

Emic and Etic PerspectivesWhen looking at any culture, our own or someone else's, it is possible to have two different perspectives. Being an ethnographer requires the ability to move easily from one perspective to the other. These two perspectives are emic and etic. The words are derived from linguistics, but have different meanings as used in cultural anthropology. Emic PerspectiveTo gain the emic perspective on a culture means to view the world as a member of that culture views it. If you were born and brought up in one culture, you have been socialized to the emic perspective of that culture. You have acquired a view of the world which provides explanations for most of what you experience, as well as providing motives for your own and others actions. An outsider to the culture can learn an emic perspective, but it takes both time and the suspension of ethnocentrism. An emic view, for example, will enable you to explain all the nuances of finding a spouse in Pakistan, or how U.S. teenagers find dates. Obtaining an emic view of another culture is a central goal of doing ethnography, and an emic view is necessary before an etic perspective can truly be obtained. Etic PerspectiveTo gain an etic perspective on a culture, your own or someone else's, requires even more work. Not only do you need to understand the emic perspective of the culture in question, you must also be able to emotionally detach yourself from that culture, in order to arrive at objective, testable hypothesis to explain observed behavior and beliefs. It is an "outsiders" view in the sense that it requires one to become a detached, objective, scientific observer of that culture. Most people from outside a culture will not have an etic perspective about it; they will have an ethnocentric perspective, interpreting behavior and beliefs in light of their own culture. Most people from inside a culture will not have an etic perspective about it; they will have an ethnocentric perspective, interpreting behavior and beliefs in light of their own culture. An etic description must be able to generate scientific theories about the "causes of sociocultural differences and similarities." While emic description uses language and concepts that are appropriate from the native point of view, etic description uses language and concepts drawn from social science. As a result, an etic viewpoint is often unfamiliar to the native, whether we are talking about a native U.S. citizen or a native Yanomamo.

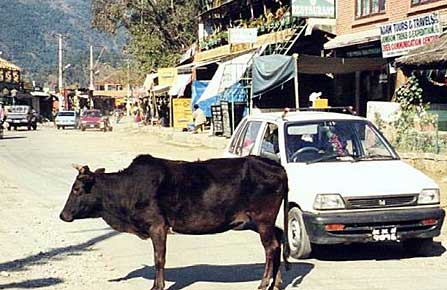

"Unattended" Cow Presents Street Hazard in India Anthropologist Marvin Harris, who coined the terms emic and etic, did considerable fieldwork in India, where Hinduism is the dominant religion. The Hindu religion prohibits the slaughter of cattle or the consumption of beef. India's sacred cattle have been used as the basis for the English expression "sacred cow", which can be used for any group clinging to something which is viewed objectively as irrational. It is an ethnocentric view of practices in India, which assumes that killing and eating cattle would help feed people, prevent traffic hazards, and improve India's economic development. (Click here for more on this subject; topics are on the right; click on "video" for a very brief video on the sacredness of cattle in India.) Emically, most Hindus do not kill cattle because they believe it is morally wrong, because they find the act of killing a cow emotionally and spiritually repulsive and defiling, and because they would literally be sickened from eating beef. McDonald's Restaurants in India serve muttonburgers instead of hamburgers, and one was recently attacked for using some beef fat in the oil for french fries. An etic explanation of the origin of the taboo on slaughtering cattle emphasizes their traditional importance in agriculture. Cattle were and are used in rural India to pull the plow, to pull carts, to provide fertilizer and fuel, and for milk. Because of their ecological and economic importance, Harris argues, preserving the lives of cattle was adaptive in Indian culture. Since in times of serious food shortages, farmers might be tempted to slaughter their cattle for food, a religious taboo developed to prohibit it. A farmer who killed his cattle during a food shortage would surely die, as he would be unable to plant and harvest his next crop. Even today, an etic argument can be made for the practices in India. Of India's over one billion people, close to 75% live in rural areas. Most farmers have only about an acre of land, and mechanization would be impossible. Chemical fertilizers are also too expensive for most farmers. Fuel remains a problem in India, and many rural people still cook using cow dung for the fire. (Wandering cows are usually followed by a child who collects the dung and takes it home.) Milk and milk products remain an important part of the diet. An argument can be made that cattle are still vital to India's economic well-being, and the religious taboo is in fact an adaptive practice. In fact, some believe that America's reliance on technology is our "sacred cow", and that we would be better off with some of India's agricultural practices. (For more on Indian farming and its dependence on cattle, read the brief article Sacred Cow.)

Cow pies (dung) drying on a brick wall in India. Etically, then, the taboo on killing and eating cattle is adaptive. Clearly, an etic explanation is not an ethnocentric explanation. |