Levirate, Sororate, Ghost Marriage and More

As noted earlier, every culture must satisfactorily provide for the care and socialization of children in order to survive. That is one of the major functions of marriage, since it assigns the group responsible for care and socialization. In matrilineal and patrilineal cultures, that group is not the nuclear family, but the lineage as a whole. The lineage is responsible for all children of the lineage, and it is from his or her lineage that a person obtains their rights to use certain areas of land, their rights to live in certain houses, and often their prestige.

The lineage responsibility for the children, plus the practice of brideprice, in part explain the practices of levirate and sororate.

Levirate

In our culture, if a woman's husband dies, leaving her, say, with three small children, her economic status tends to plummet. If the woman is lower middle class, or lower class, the death of her husband is likely to be her (and her children's) ticket to poverty. In addition to the economic effect, the loss of a parent often has a traumatic emotional effect on young children. The fact that the woman has three young children also decreases the probability of remarriage in many cultures. Levirate avoids all these problems.

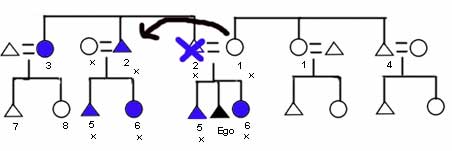

In levirate, when a woman's husband dies, she is expected to marry his brother (or at least a male in her dead husband's lineage). The diagram below illustrates levirate.

Levirate

I have illustrated levirate along with patrilineal descent (people in blue), patrilocal residency (x's) and an Iroquois terminology system, since levirate is often associated with all three. Notice that levirate means that Ego and his brother and sister do not physically move, since they have been living in the same household with their mother's new husband from the time they were born. In fact, they have been calling him the "father" term all their lives. Their economic level does not change, since it was the patrilineage as a whole that was always responsible for their care, as well as their socialization, not just their father. The economic level of their mother does not change either. She is able to stay with her children in their lineage. If a brideprice was paid when she married, there will be no question that some of brideprice should be returned, as might be the case if she left her dead husband's lineage.

While the woman might marry an unmarried brother or male of the lineage, if available, almost all patrilineal societies permitted polygyny due to levirate. Americans always ask "But what if she doesn't want to marry her husband's brother?" In fact, she often did, since it solved so many potential problems. If her children were grown, she might simply stay with her sons without remarriage, if she so chose. In any event, cultures with levirate tended to be more concerned with the welfare of the children than with their mother's freedom of choice.

Traditionally, the Yanomamo, traditional Hmong, and the Nuer had levirate, at least some of the time. While relatively rare among the Hmong in Laos, in increased greatly in frequency due to the Vietnam War. The death rate among male Hmong was such that many clan elders married the widows of their younger brothers or other young men of the clan. Subsequently, this led to many "divorces" of wives in order for everyone to immigrate to the United States. Nonetheless, in the United States, Hmong men continued to assume responsibility both for their one legal wife (in the U.S. view) as well as their "ex" wives who were their brothers' widows.

Sororate

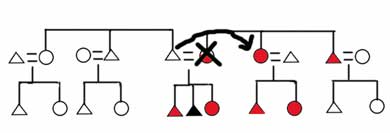

In sororate, when a man's wife died, he was expected to marry her sister. Again, an unmarried sister or other female of the same lineage would be the preferred choice, but polyandry might be permitted in cases of sororate.

Sororate

Sororate, shown above in a matrilineal, matrilocal culture, functioned in much the same way as levirate. It was sometimes practiced in patrilineal, patrilocal societies with preferred cross cousin marriage. If a man had married his cross cousin, than her sister was probably married already to his brother. The sister would than have two husbands, but the children would stay within their father's patrilineage.

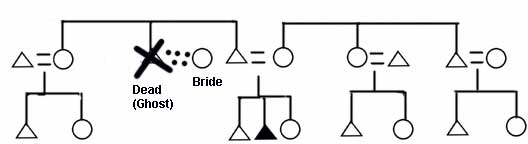

Ghost Marriage and Woman-Woman Marriage

The Nuer had two other rare, but occasional forms of marriage. I have already mentioned that men were expected to bring children to their lineage. If, as sometimes happened, a young man died before he could have children, it was assumed that his spirit or soul was unhappy. An unhappy soul might stay here on earth as a ghost (a technical anthropological term meaning the soul of a dead person that stays on earth!). If this happened, the unhappy ghost might cause sickness and other misfortune for his lineage. In an attempt to placate the ghost, the lineage might negotiate and pay the brideprice for a bride for their dead relative. The ghost would then have children with the new wife, who would of course belong to their father's lineage.

Ghost Marriage

Since obviously a ghost can not father children, what normally happened was that the new bride formed a permanent liaison with one of the live men of her ghost husband's lineage, most likely one of his brother's. The brother was the biological father of her children, but her ghost husband was the cultural father. The children of course were the responsibility of the lineage as a whole.

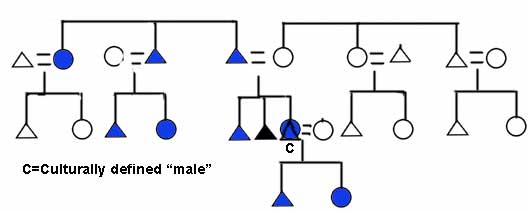

Woman-Woman Marriage

Woman-woman marriage was also found among the Nuer. In the article on Nuer Marriage, notice that the newly married woman initially continued to live at home. Only after the birth of her first (and sometimes second) child did she actually move to her husband's household according to the rules of patrilocal residency. This was because the woman might prove to be infertile. If she could not produce children for her husband's lineage, a divorce would occur, and what ever portion of the bride price that had been paid would have to be returned by her lineage or clan. The woman would have to return to (or remain with) her own patrilineage, but they would be unable to arrange another marriage for her, since it had been proven she could not have children. Her lineage might than culturally reassign her to be a "male", and pay the brideprice so that "he" could get married. The new bride would move in, and ultimately her children would belong to their "father's" lineage, as illustrated below.

Woman-Woman Marriage

Of course, the biological father of the children would be the cultural "male's" brother, or some other man of the patrilineage. Normally, the wife would form a stable sexual relationship with one specific male in the lineage. Woman-woman marriage enabled a sterile woman to have children, and to contribute meaningfully to her lineage. It also gave her a place in a culture where all adults were married. Except for ceremonial purposes, the woman continued to have the female role in the culture; with ceremonial activities involving the children, she became their cultural "father". This practice did not indicate any homosexual relationship between the two women, and the "cultural male" often had discrete sexual affairs with men who were not of her lineage.

|