|

The Nuer of the Upper Nile RiverFrom: Profiles in Ethnology, by Elman Service This account was written by Elman Service on the Nuer, with most of the information taken from accounts of ethnographer Evans-Pritchard. The Nuer and the Dinka are two linguistically similar cultures, both practicing cattle pastoralism. They live in the Sudan and in Ethiopia. Those in the Sudan have been largely killed or displaced due to civil war in the southern Sudan, which killed over 2 million people from the early 1980's until it officially ended in January of 2005. [The recent and deadly civil war in the south is not the current conflict in the Darfur region, which started in 2003.] This article presents the Nuer as they were between 1940 and 1980. General BackgroundThe south-central part of the Republic of the Sudan, the homeland of the Nuer [and a related pastoral group, the Dinka], is a great open grassland traversed by the Upper Nile River and its several tributaries. The climate is tropical and the year is divided almost equally between a very dry season and a very wet one. From December to June the rivers are low and the blazing landscape is parched and bare. From June to December the rainfall is heavy, and the rivers overflow their banks and nourish a heavy growth of high grasses... The Nuer total about 300,000 people [a 1960's statistic-today they number approximately 1 million], but there is no political unity of the whole group. Nuer refers not to a nation or kingdom, but to contiguous tribes who are similar culturally and linguistically and who sense this likeness to the degree that they feel distinct as a group from neighboring peoples. The Dinka, long-time enemies of the Nuer, are more similar to them than the other nearby groups, and it is probably that the two were once a single cultural-linguistic unit... The Nuer are essentially pastoral, although, like many of the other herding peoples of the world, they grow a few crops when poverty demands and where soil and climate permit. But to the Nuer, and to all the East African pastoralists, horticulture is degrading toil, while cattle-raising is viewed with great pride. Cattle represent the main source of food in the forms of milk, meat, and blood; the skins are used for beds, bags, trays, cord, drums, and shields; the bones and horns are made into a wide variety of tools and utensils; and the dung is used as a plaster and as a fuel. Cattle are by far the most cherished possession, and the Nuer seem to be interested in them nearly to the exclusion of anything else. E.E.Evans-Pritchard writes: "They are always talking about their beasts. I used sometimes to despair that I never discussed anything with the young men but livestock and girls, and even the subject of girls led inevitably to that of cattle..." Milk is the staple food of the Nuer all of the year. It is drunk fresh, mixed with millet as a porridge, allowed to sour for a particularly relished dish, and churned into cheese. Milking is done twice daily by women and children; initiated men are forbidden to milk cows unless for some reason there are no women present to do it. During the dry season, when food is scarce and when cows are running dry, the Nuer bleed their cattle from a small cut in a neck vein. Blood is boiled until thick or is allowed to stand until it is coagulated into a solid block, after which it is roasted and eaten. Cattle are not raised expressly for the meat; but when they become barren, injured, or too old for breeding, they are butchered and eaten under festive and ritualized conditions. The Nuer men are devoted to their cattle. After the women have milked the cows, the owner escorts the herd to pasture and to water, oversees them all day, and brings them back at night, meanwhile singing songs he has composed describing their virtues. In the evening he goes among his favorites, cleaning ticks from them, rubbing their backs with ashes, and decorating the horns with long tassels. The Nuer wash their hands and faces in the urine of cattle, and they cover their bodies, dress their hair, and even clean their teeth with ashes made form cattle dung.

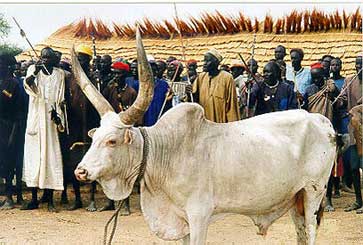

Nuer bull about to be sacrificed at a year 2000 meeting between Dinka and Nuer The crops cultivated by the Nuer are millet (sorghum) and some maize. Next to milk, millet is the most important food. It is made into a boiled porridge and also brewed into a weakly alcoholic but nutritious beer. A little maize is eaten, but it does not grow nearly as well as millet under the wet conditions. Goats and sheep are interspersed among the cattle, but are not considered important. Fish is the other significant food. At the onset of the dry season the lagoons and small rivers begin to drop and fish are easily speared in the dammed pools. The territory is rich in game, but the Nuer do not hunt intensively. Many kinds of antelope, buffalo, elephant, and hippopotamus are plentiful, but the Nuer feel that only a man poor in cattle will bother to hunt for food. Lions and leopards are a threat to the herds in the dry season, and the Nuer hunt them in self-protection, relying on dogs and the spear. The Nuer do not keep domesticated fowl, and they regard the eating of the plentiful wild birds or their eggs with repugnance. During the rainy season, the Nuer live in villages located in the areas of higher ground and cultivate their small gardens. So rare are these spots and so uninhabitable are the extensive flooded areas that as many as from five to twenty miles separate one village from another. The size of the village is determined by the extent of the habitable and cultivable ground,and one village may contain from fifty to several hundred persons. At the end of the rainy season, after the ground has dried off, the villagers set fire to the grass to make new pasture and set off to camp near streams and rivers for the next six months. Frequent movements during this season are necessary as the pasturage becomes more and more sparse. There are no permanent land rights among the Nuer. A village selects its site with the idea that land for all would be available. Cattle are individually owned--in fact, they are almost members of the family, so carefully are they tended--and some families are somewhat richer in cattle than others. This variation is closely related to the prestige of the owner, but it does not result insignificant differences in the standard of living. The degree of sharing [reciprocal exchange] in a community, and even among neighboring communities, is such that a whole group seems to be partaking of a common stock of food. Anyone is privileged who, through luck or the possession of more or better cattle than others, is better enable to provide for the less fortunate. There is no trade, the technology is poorly developed, and at certain times of the year, especially late in the dry season, there is a real shortage of food. The Nuer community is thus required to act as a corporate economic body. As a quick survey of the 'primitive' world clearly shows,it is scarcity and not wealth which makes people generous. KinshipAll members of a village or camp are kindred, as indeed, at least by fiction, are all people with whom a Nuer associates. All rights, privileges, obligations,in fact, all of the customs of interpersonal association, are regulated by kinship patterns; there is no other form of friendly association--one is a kinsman or an enemy. Genealogies are lengthy and well remembered, so that a Nuer can place into the proper category nearly any individual with whom he is likely to have contact. Nuer kinship terms are classificatory, however,which is to say that the terms applied in direct address to members of the immediate family include other relatives who have an age and type of association in some measure analogous to that of a particular member of the immediate family. On most social occasions it is a point of courtesy to designate a relative, no matter how distant, by a term denoting a member of the immediate family. Thus all male relatives in one's parents' generation are usually called father and all women mother; relatives of one's own generation are addressed as brother or sister; the children of one's own generation are called sons and daughters. The maternal uncle is, as in many societies, considered to have a rather special relationship to his nephew, in comparison to the other males of the uncle's generation, and frequently, though not always, he is designated by a separate term... Relative age is of great importance in Nuer interpersonal relations and seems to take precedence over genealogical considerations to a considerable degree. Every person in Nuer society is categorized explicitly in terms of an age-set system. All males are divided into age grades so that each one is a senior, equal or junior to any other male. One is deferential to a senior, informal with an equal, superior to a junior. Women belong in the system as mothers, wives, sisters, or daughters of the particular males. The relativity of age, therefore, rather than genealogical relationship frequently governs the use of kinship terms in address. Anyone of an older age-set is addressed as father or mother, and the younger as son or daughter. Very old people are called grandfather or grandmother. Men of the same age-set, if they are well acquainted, call one another by personal ox names--i.e., the name of a prize ox is applied to the owner. Despite the generous extension of the few kinship terms to such a great number of people, there are important differences in sentiments and behavior among relatives of different kinds. A person is related to certain persons in a patrilineal line and to others through women and affinal relationships. The membership in an exogamous patrilineal descent line is the most significant relationship. This is the lineage of closest relatives--not necessarily closer in a territorial sense, but significantly closer in the feeling of relationship. This is why the maternal uncle is sometimes addressed by a special term, while the paternal uncle is a father; the latter is a member of the speaker's own lineage, but the mother's brother, of equal genealogical standing, is of the affinal lineage. Lineage membership means participation in a group that shares territorial rights, that has common political and juridical obligations (as in a feud or in warfare), and that owns certain ceremonial rights. [Corporate functions.] Villages commonly have members of two or more different lineages within them, and a given lineage has members in different villages. The lineage thus plays, in a sense, a political role. All of the people in a village naturally have a strong feeling toward their village--it is in some ways a corporate entity whose members share many economic and social activities. So, too, they are all relatives, but the relationships may be through the mother or may be of affinal as well as genetic relationship. The lineages do not permit marriage with a fellow member, but members of the same village frequently marry. Lineage membership thus cross-cuts these village units and creates larger entities out of segments of otherwise independent villages. Related lineages from a still larger, more amorphous group, the clan. A person knows the precise genealogical position of each member of his lineage, but clans are viewed as composed of lineages, not of individuals; the genealogical-like relationship of each lineage to another in the clan is known, but the individuals are known only as fellow clan members, all descended from a common ancestor. Villages, Tribes, and GovernmentVillages are units of common residence. Several villages together occupy a territory that they feel to be theirs by custom and occupation. There is a tendency for this felt relationship of villages to be signified by a common name, a district name, which is at the same time a name of the group of people in it. Several of these districts feel a kinship to others in a larger territory, and again these to another, and finally the ever more attenuated recognition of unity peters out. This final area of recognition of communality is the tribe. The Nuer, as a whole people, are divided into eight or nine large tribes, averaging about 5000 persons each, and several much smaller ones. But the tribe is the largest unit of persons who defend a common territory, who are a named group, and who act together, manifesting a sense of patriotism or belongingness... Each Nuer tribe consists of several clans, but always there is one which is felt to be the oldest and most distinguished. It is sometimes, but not always, the largest as well. A clan tends to have at least some members in each of the many villages of the tribe, but always one particular clan is felt to be the most important in each village...It is a matter of prestige, however, and not of privilege. There are no economic classes based on inherited differences in wealth or standards of living. Nuer tribes have no true government or regularized authority, no laws or lawgivers. There are, to be sure, influential men, but these men have a degree of authority which rests on their individual abilities to command respect rather than on inherited status or function...The Nuer are strongly egalitarian and do not readily accept authority except in familial ways implicit in the age and sex categories of the kinship system. The position most closely resembling political office is that of the Leopard-skin Chief, so called because he is entitled to wear a leopard-skin wrap. His main function, in addition to certain ritual duties, is to mediate feuds. The most serious social disturbance in Nuer life occurs when one man kills another. As in other societies without governmental institutions, this act inevitably brings retaliation from the bereaved kinsmen and is frequently the beginning of a true feud. Nuer communities do not let this situation go uncontrolled, for the society is not wholly anarchic, yet no judgment or force of a legal or governmental sort is involved in the settlement. When homicide has been committed, the killer goes to the local Leopard-skin Chief, and if he fears vengeance at that time, he may remain with the chief, whose home is a sanctuary. The role of the chief is to go to the family of the slayer and elicit from it a promise to pay a certain number of cattle to the aggrieved, after which he attempts to persuade the family of the dead man to accept this compensation. He is only a mediator, however, and he has no authority to judge or to force either a payment or its acceptance. On the surface, there seems to be a government-like characteristic involved--a restitution rather than retribution is provided--but it is not a payment to the state or society as such, or in any sense a fine or sentence. Occasionally the Leopard-skin Chief acts as a mediator in other kinds of disputes, such as cases involving a disputed ownership of cattle. He, and perhaps some respected elders of the community, may express their opinions on the merits of the case and attempt to argue the two sides into a settlement. But again, he has no official power. He does not summon the defendants, and he has no means of enforcing compliance with his opinion.

|