|

Traditional HmongYour main source of information on the Hmong is the book The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, by Anne Fadiman. In addition, you should read both the Hmong Chronologies that are provided and assigned with the lessons. The book provides a wealth of information on the traditional Hmong culture and lifestyle as they lived it in Laos, prior to the Vietnam War. Whenever a question in the study guide asks about traditional Hmong culture, it is referring to the Hmong as they were in Laos, prior to 1964. By the end of the War, in 1975, much of the traditional lifestyle could no longer be practiced, and the necessity for the Laotian Hmong to flee for their lives to Thailand and refugee camps destroyed much of what remained. Though the Hmong had managed to preserve their lifestyle and their mode of production through migration from China, through French colonization, and finally Japanese occupation, the Vietnam War made it impossible for them to survive as a horticultural people. However, as the book makes clear, they brought many of their values, beliefs, and practices to the US when they came as political refugees in the period from 1975 to 2004. (See Chronology 2) Prior to their involvement with the US in the Vietnam War, the Hmong were in many respects a typical horticultural society. If you are familiar with the traits of a horticultural mode of production--as you need to be for the unit exam--you already know many of the traits of the traditional Hmong. (For traits of horticultural societies, check lessons on New Modes and Horticulture, and Chapt. 6 in text. What follows is a brief summary of some (very little) of the information that is found in the Spirit book. Read the book for complete information. HorticultureHorticulture is a mode of production dependent upon domesticated plants, with or without animals, and without plows. The Hmong depended upon growing rice, in large fields in the mountains of Laos. They also grew many kinds of vegetables, and maize or corn, which was primarily fed to their livestock. The Hmong were horticulturalists with domesticated animals, which included chickens, pigs, cattle, horses and mules.

In addition, as the book noted, the Hmong grew opium poppies. The raw opium was used sparingly by Hmong, and was also used by the religious specialists, the shamans or trix neeb. The Hmong, remember, were very different from horticulturalists like the Yanomamo, who were isolated from other cultures and modes of production. The Hmong for centuries had close association with intensive agricultural states, both in China and in Vietnam, Laos and Thailand. Once in Laos, opium provided the Hmong with a cash crop which could be traded with agrarian and eventually industrial states. The French encouraged them to grow opium after taking over Laos, as taxes had to be paid in cash originally, and eventually could be paid in opium itself. Hmong horticulture was primarily swidden or slash and burn horticulture, which meant that their fields were exhausted in ten or twenty years, and they would have to move their villages. Laos was home to other hill tribes, who were were also horticulturalists, and the lowlands were densely populated by the dominant Lao ethnic group, who also controlled the political state of Laos. As a result, as populations expanded, (and like most horticulturalists, the Hmong liked large families) arable land could be a problem to find. The Hmong often had to return to areas for cultivation before the soil could completely recover, and there were fewer areas available that had never been cultivated. It became harder for the Hmong to raise sufficient rice for their own consumption, and the cash earned by selling opium became more and more important for their survival. As industrialism spread, there were also more useful items that the Hmong could purchase with their cash. Though basically a horticultural society, they were tied to the outside world long before the Vietnam War, and Laos was already a major supplier of opium and its derivatives, morphine and heroin, to the world market. (In this respect they were completely unlike the other horticultural society you have read about, the very isolated Yanomamo.)

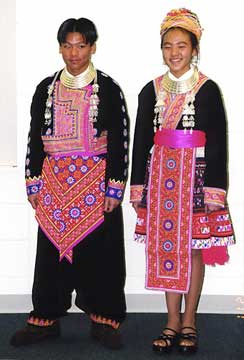

Opium poppies, almost ready for harvest The Hmong also cultivated hemp, which they used to make clothing. Traditionally Hmong women processed the hemp into thread, wove the cloth, which was usually batik-dyed, and made the clothing. For themselves, women made the pleated skirts and embroidered clothing which remains the traditional dress. Hemp clothing was also taken by a girl to her husband's household upon marriage, and it was considered necessary for funeral ceremonies. To see some photos of the process of making hemp clothing by the traditional Hmong, click here. The cover of your text also features Thai Hmong in traditional hemp clothing, with a loom in the background.

Traditionally, the clothing would have been made of hemp. Social StructureThe Hmong, like most horticultural societies, had unilineal descent, specifically patrilineal descent. Their largest kin group was the patriclan, which tended to own property use rights. Horticultural activities were usually carried out collectively by the clan. Clan elders were arbitrators of disputes within and between clans, tended to make arrangements for marriages, and were respected by all. Clans were of course exogamous. Since residency was patrilocal, the girl's clan received a brideprice when she married, which was usually paid in silver neckrings or cash. Polygyny was possible but uncommon, though practiced as part of levirate.

Hmong girl wearing silver neckrings; traditionally the Hmong produced them by melting and molding silver coins. Other Cultural TraitsThe Hmong, at the time they moved into Laos, were tribal and egalitarian. However, because the clan was the basic economic unit, some clans were larger and able to produce more than others. Though the French did not change the clan structure, some clans were more favored by the French than others. In addition, the French started the process of undermining the authority of clan elders, often by dealing with younger men, particularly those who had received some education. Hence even before the Vietnam War, the Hmong were not entirely egalitarian. Clearly they retained their tribal nature however, and as the book made clear, at least one major clan did not side with the French and later the Americans, but supported the Pathet Lao. Religious beliefs as well as many other values and beliefs of the Hmong are thoroughly presented in the book. In Unit 3, I have provided a synopsis of Hmong religious beliefs. |