Horticulture, the mode of production discussed in the last unit, was in many respects a very successful mode. As populations rose from the first horticultural areas of present-day Iraq, SE Asia, northern China, Mexico, and Columbia/Peru, people migrated. As horticulturalists migrated, they took their crops with them, and modified these crops for new environments. Within 6,000 years horticulturalists had spread to almost every environment where farming is possible today. Only a few areas of the globe, mostly too dry or too cold for farming, were left to the foragers and the pastoralists.

Horticulturalists continued to increase in population size. The cultural materialist model of cultural change (last lesson Unit 1) may well have applied. Faced with a threat to their standard of living, climate made further migration impossible. Horticulturalists had no option but to intensify production (perhaps by developing chiefdoms) , and to make the technology of production more efficient. Since both options tended to deplete the environment, horticulturalists went through several cycles of intensification and technological change, until finally, in a few areas, they developed a new mode of production. In anthropology, this mode is known as intensive agriculture, or the agrarian state.

As was true of horticultural, intensive agriculture represented a change in all aspects of culture. (Remember, cultural materialism states that most values, beliefs, and practices of a culture are determined or limited by its mode of production.)

Intensive agriculture, often called in history the "rise" of civilization, first began just prior to 3,000 B.C., in what is now Iraq. The first political state, called Sumer, began there in the area historically called Mesopotamia, in modern-day Iraq.

Other major areas for the early agrarian state include Egypt, the Indus River (Pakistan), northern China, Mexico, and Peru. While anthropologists rarely use the value-laden term "civilization", if they do, they mean the agrarian state, or intensive agriculture.

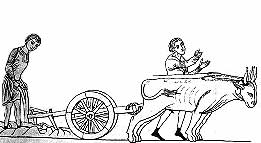

Intensive agriculture represented increased energy investment per unit area of land, often by massive amounts of human labor invested in irrigation, drainage, and/or terracing systems. Animal energy was also invested in food production in the form of animal muscle and fertilizer. Farmers increasingly became dependent upon complex technology, which required materials or skills not found in each farming family. The metal plow is common, and intensive agriculture is often called plow agriculture as a result. It is the intensification of human labor (humans worked longer and harder than horticulturalists in a year and in a lifetime) that has led to this modes most used name, intensive agriculture.

These three traits, along with market exchange (see next lesson) were ultimately incorporated into all industrial states as they began to develop in the 1600s. All three are of course found in our culture.

Interestingly, and illogically, in all the early agrarian states, the food producers were typically at the bottom of the class system. The food producers in fact became peasants. Peasants are farmers who lacked control over one or more of the means of production: land, water, labor, technology, or knowledge. Usually 60-90% of the population of agrarian states are peasants. For the peasants, this mode of production typically meant that they worked harder than horticulturalists, often for a poorer diet, a similar or shorter life span, less control over their lives, and more diseases.