THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

Geography 101

ToC

MOUNTAINS

Crust

Folding

Earthquakes

Volcanoes

Hawai'i

Earthquakes

|

|

BOX 1 |

The rumble and shaking of earthquakes seems a terrifying change from normal for humans, but considering Earth's gigantic plate collisions, warping, volcanism, and other mountain building, it is perhaps surprising that they are not more common.

Huge, lumbering, rigid lithospheric plates do not slide smoothly past one another. Instead, they lurch, grind, stop, creep, and seize by friction, as you would expect from any two solid objects rubbing against one another. When plates stop moving relative to each other, tremendous pressure builds and when they finally lurch onward, this energy is released suddenly as a seismic wave, which moves by compression and tension in rock. Like clapping your hands produces a sound wave, sudden movements in Earth's lithosphere produce seismic waves, which we feel as earthquakes.

The vast majority of earthquakes occur at plate boundaries.

This correlation is so dependable that plate boundaries have been mapped

using earthquake location data.

The vast majority of earthquakes occur at plate boundaries.

This correlation is so dependable that plate boundaries have been mapped

using earthquake location data.

The map shows the global distribution of earthquakes. The plate boundaries become immediately obvious. Notice that the edges of the Pacific plate are particularly active. Remember, in geologic time, the Pacific is slowly shrinking while other oceans, like the Atlantic, are growing larger. Because it is shrinking, active subduction zones encircle virtually the entire the Pacific Basin. The accompanying huge circle of earthquakes and volcanoes has been called the "Pacific Ring of Fire."

Properties

When seismic energy is released, energy radiates out from the center of movement. This spot is called the earthquake focus and the location at the surface directly above it is the epicenter. For larger earthquakes, the seismic wave travels through the entire Earth. In fact, most of what we know about Earth's interior has been inferred by studying the characteristics of seismic waves produced by earthquakes.

|

|

|

When a seismic wave reaches the surface, the energy produces several motions. The fastest traveling motions are called P-waves (for primary). They cause stretching and compression in the crust, like an accordion or slinky toy, and seldom cause much damage. Next come the slower, but more dangerous, S-waves (for secondary), which cause the ground to whip from side-to-side. Finally, the slower surface waves arrive with both rolling and side-to-side movements. Together, these motions produce forces that challenge any structure built by humans.

Earthquake

intensity is measured using a logarithmic scale, which means that each

integer number increase represents a 10-fold increase in

intensity. In other words, a magnitude 6 earthquake is 10 times greater

than a magnitude 5, 100 times greater than a magnitude 4, and so

on.

Earthquake

intensity is measured using a logarithmic scale, which means that each

integer number increase represents a 10-fold increase in

intensity. In other words, a magnitude 6 earthquake is 10 times greater

than a magnitude 5, 100 times greater than a magnitude 4, and so

on.

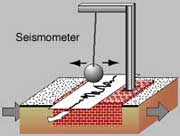

The Richter scale is the most widely recognized logarithmic measure of earthquake intensity. Richter based his scale on the actual movement of the ground, recorded by a seismometer. As shown in the illustration, a recorder with a heavy weight is suspended by a wire. When an earthquake occurs, the entire instrument moves underneath the weighted recorder. The greater the earthquake, the greater the ground movement, and the greater the line displacement on the recording chart. Today, scientists use a modified scale that takes into account the actual amount of energy released at the focus, not just ground movement.

Humans generally cannot feel earthquakes of less than magnitude 3. Between 3 and 5, they can be felt, but seldom cause damage. Above 5, damage is probable, and anything above 7 will certainly cause widespread ruin of human-built structures. The rare earthquake that measures 8 or above is given special respect, somewhat like naming hurricanes, and is referred to as a Great Earthquake. Examples include the San Francisco quake of 1906 and the Lisbon, Portugal quake of 1755, which killed over 60,000 people.

Hawai'i

The Hawaiian Islands are one of the most earthquake-prone places on the planet, despite the fact that they lay nowhere near a plate boundary. The vast majority of quakes occur in or near the Big Island and are smaller than magnitude 3, meaning they cannot be felt by residents. Sub-surface movements of magma cause these small tremors.

Other

quakes are apparently caused by scraping motion at the base of the

lithosphere and by faulting

within the fractured mass of the Big Island itself. These are potentially

much larger and more destructive. In 1975, a magnitude 7.2 earthquake

centered on Kalapana

accompanied a movement that dropped the surface 3.4 meters (11 feet) along the

coastline, destroyed houses, sank boats and generated a local tsunami

that claimed two lives. In 2006, a 6.7 magnitude quake caused widespread

damage to structures in North Kona and Kohala on the Big Island and

knocked power out on O'ahu for most of a day. The largest known quake

occurred on April 2, 1868. Estimated at magnitude 7.9, it caused widespread

damage over the entire Big Island and was felt as far away as Kaua'i.

Other

quakes are apparently caused by scraping motion at the base of the

lithosphere and by faulting

within the fractured mass of the Big Island itself. These are potentially

much larger and more destructive. In 1975, a magnitude 7.2 earthquake

centered on Kalapana

accompanied a movement that dropped the surface 3.4 meters (11 feet) along the

coastline, destroyed houses, sank boats and generated a local tsunami

that claimed two lives. In 2006, a 6.7 magnitude quake caused widespread

damage to structures in North Kona and Kohala on the Big Island and

knocked power out on O'ahu for most of a day. The largest known quake

occurred on April 2, 1868. Estimated at magnitude 7.9, it caused widespread

damage over the entire Big Island and was felt as far away as Kaua'i.

The map below shows the location of historic earthquakes on the Big Island and the table documents significant events.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table and map from US Geologic Survey (*estimated) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||