The previous unit examined the spread of horticulture into Europe, and the establishment of various though diverse farming populations by 3,000 BC., as well as the early megalithic-building peoples. Copper and bronze metallurgy had diffused to Europe via Mycenae and other Mediterranean trade routes by 2000 BC, along with horses, chariots and other items. Europe rapidly developed various stratified chiefdoms, and since Europe was already part of the trade routes, iron smelting was adopted some 1,000 years after the earliest evidence that people smelted iron ( at some 2,000 BC, in Turkey.) North of Greece, and ultimately of Rome, Europe remained an area of feuding chiefdoms. Some of these--and specific sites such as Borum Eshoj in Denmark and Vix in northern France--are discussed in the text on pp. 542-558.

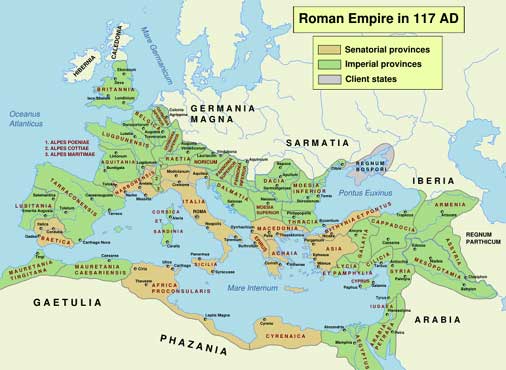

The collapse of Alexander's empire in 323 BC lead to the resurgence of smaller states and empires in the area of southwest Asia, northern Africa, and southern Europe. Greece entered its so-called Hellenistic period, and the cities of Alexandria in Egypt and Antioch in Syria were examples of a renaissance of Greek culture outside of Greece. The resurgence of Persia in the form of the Parthian Empire in 224 BC (see lesson on Persia) was closely followed by the emergence of Rome beginning approximately 200 BC. Starting as essentially a small city-state in Italy, Rome expanded to control much of the area by 117 AD, including all of Greece, Mesopotamia, northern Africa, and much of Europe.

Map of Roman Empire at Greatest Extent

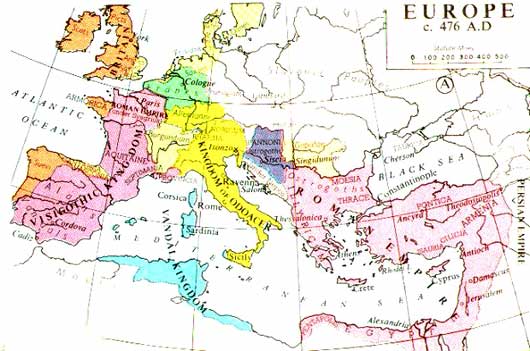

While the conquests of Rome to the east and south were against agrarian states of various sizes, the Roman conquests to the north were against a variety of competing horticultural chiefdoms. As Rome spread, it also spread Christianity, since Rome had become officially Christian in 313 AD. On a regular basis, more nomadic pastoralists, also organized as chiefdoms, swept in from the east steppes, displacing previous populations and often threatening Rome itself. As so often happened when a state-organized culture conquers chiefdoms, when the power of Rome declined, it left behind small competing states (not chiefdoms) throughout the area it had once controlled. Rome was in decline by 395 AD, and in western Europe had totally disappeared by 476 AD. The Eastern Roman Empire, really the continuation of the Roman Empire, is better know historically as the Byzantine Empire, with its capital in Constantinople (now Istanbul). As noted below, the Byzantines continued to be a powerful empire until weakened by the Muslim expansion, and finally conquered by the Turks.

Breakup of the Roman Empire; Europe ca. 476 AD [Public Domain]

While conflicts between states and conquerors in Europe continued, this lesson will focus on two threats, one from outside Europe, and one from inside. These are the Islam and Arab expansion, and the Viking diaspora.

The founder of the Muslim faith, Muhammad, was born in what is now the Saudi Arabia city of Mecca, in 570 AD. Finding local opposition to his version of monotheism, Muhammad left Mecca for Medina in 622 AD. Within a few years, all the Arab tribes were united under Muhammad. After his death in 632, the real period of Arab or Muslim conquests by Arabia began. To the north, between 637-639 Arabia conquered Syria, Palestine, and Armenia, taking territory from the Byzantine Empire. They moved into northern Africa, taking Egypt by 639 and the rest of north Africa by 665. In 642 the Arabs conquered the third Persian Empire. From Persia, Muslim invaders moved into the Indus Valley and India proper, conquering all of what is now Pakistan by 711.

Pushing further eastward along the major trade routes to China, the Arabs were at the Chinese border when defeated by China in 751. To the west, between 711-718, the Arabs conquered the Iberian peninsula (present-day Portugal and most of Spain). By 827 the Arabs had conquered southern Italy, and in 846 sacked Rome.

Resistance slowed their expansion, finally bringing it to a halt in many areas. In many other areas of northern Africa and Asia, the Arabs were replaced by small independent kingdoms, but those kingdoms remained loyal to Islam. One of them was a group in western Turkey, the people who became the Ottomans.

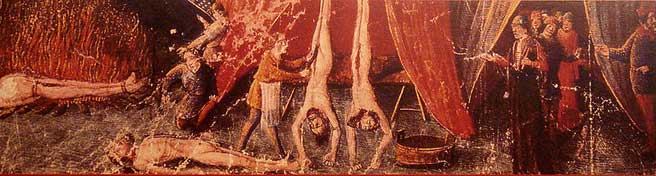

Both the Byzantine Empire and the various small Christian kingdoms of Europe were to spend the next several hundred years trying to regain control of lost territory. The Byzantine Empire called upon the Pope and the Christian states of Europe for assistance. As a result, some nine Crusades were launched between 1095-1272 against Muslim areas, particularly Jerusalem. The Crusaders without question thought they were carrying out the will of God; for the Muslim world, the Crusades are known as a time of atrocities, since the Crusaders captured and executed civilians and soldiers alike, and at least in the early Crusades, mutilated bodies. Ultimately, in 1492, Spain pushed the remaining Muslims out of the Iberian peninsula, the last occupied area of western Europe.

Crusader Executions and Mutilations, from a 13th century painting [Public Domain]

Shortly before western Europe was successful in expelling the Muslims, the rising power of the Muslim Ottoman Empire finally overwhelmed the Byzantines, when in 1453 Constantinople was seized by the Ottomans and renamed Istanbul. The Ottoman Empire, which began its expansion in 1293, centered on modern Turkey, was to control much of southeastern Europe, Turkey, the Mediterranean including Egypt and northern Africa, and all of the former Mesopotamia, until into the 20th century.

After Rome, much of western Europe was united under the emperor Charlemagne (768-814), but the extreme northern part of Europe continued to be inhabited by competing horticultural, and non-Christian, chiefdoms. Primarily in the modern nations of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, (collectively called Scandinavia) these people became known as the Vikings. Living far to the north on the edge of effective horticulture, the Vikings grew cold-tolerant barley and oats, and kept mostly sheep and goats; pigs and cattle were preferred by the chiefs but did not do as well in the environment. The Vikings also mined iron and manufactured a variety of iron tools, in the process consuming large quantities of wood.

In many respects the period of Viking raids in Europe, from about 790 to 1000, represents the old story of highly developed chiefdoms competing for power, wealth and prestige as some of them united larger areas into agrarian states. The Vikings were traders, raiders, and colonizers all at once. Scandinavia provided furs and seal skins to much of Europe, and in return received (or took) luxury items such as gold and silver, for the chiefs. Groups defeated by larger chiefdoms within Viking territory frequently immigrated to outside areas, founding colonies; in some cases, younger sons who did not inherit formed groups of colonizers. [This should sound a bit like the colonization of Polynesia.]

The Vikings both raided, and founded settlements in, modern England and Scotland (together forming most of the United Kingdom), Ireland and France. One Viking group, the Rus, colonized deep into what is now Russia, giving the country its name. The Vikings are also the first colonizers of two remaining island areas of the world, Iceland and Greenland, as well as the first Europeans to enter North America. Others wrote about the Vikings, and ultimately the Vikings wrote about themselves, leaving an oral and ultimately written tradition that can be tested by archaeology. [Click here, required, and then click on "Exhibit" for map of Viking voyages. This link is to an exhibit of Viking artifacts by the Smithsonian; if you like, click on "Tour Exhibit Highlights" underneath the map to see some of the artifacts.]

The Vikings settled and intermarried where they also raided (in Ireland particularly selling the men south into slavery, and marrying the women), but as a result of all the contact Christianity spread into Scandinavia. Denmark converted officially in 960, Norway in 995, and Sweden in the early 1000's, ending all Viking raids. When Norway converted, their colonies in Iceland and Greenland did also.

Iceland was colonized between 870-930 AD; by the latter date all arable land had been occupied. The colonists on the previously unoccupied island did not realize how fragile the soils were compared to that of their homeland in Norway. The immediate deforestation for fuel and to promote sheep-herding led to soil erosion; even today much of Iceland is totally barren. The people quickly turned to cod fishing, which could easily be exported to Europe, and on the whole the colony prospered.

Archaeology indicates that Greenland was first discovered by Native Americans approximately 2500 BC. These first settlers, foraging bands, disappeared, returned again, then left prior to the Viking arrival. There were no occupants on Greenland when Eric the Red, exiled first from Norway and then from Iceland (for murder), took the first European colonists there in 982 AD; others followed, until the island had a population of around 5,000, in two settlements 300 miles apart, by 1000 AD. By 1200 AD the Inuit (Eskimo) entered Greenland again, drawn by the same relatively warm climate that made parts of Greenland habitable for the Vikings.

While cattle were still the desired animal for the wealthy, sheep and particularly goats did much better in the Greenland environment. The growing season was very short, and Greenlanders used it to grow hay for the domestic animals, along with a few vegetables. When the long winters started, the farmers slaughtered any excess animals not expected to survive the winter; only then was meat plentiful, since the animals were otherwise used to produce milk and cheese. Wild caribou were hunted, as were seals in the spring, but the Greenlanders did not fish; at least, no fish bones have been found archaeologically.

In 1000 AD, according to two surviving Norse sagas which started as oral tradition and were written down some 200 years later, Eric's son Leif the Lucky sailed some 1000 miles west of Greenland and came upon North America. He called the area where he landed Vineland. Like the Polynesians, the Vikings carried domesticated animals with them in anticipation of settling any favorable new land, and they founded a colony along the coast. While over the years many sites have been offered as evidence of the Vikings, none actually illustrated anything of Viking culture, until the discovery in 1961 of a site called L'Anse aux Meadows on the northwest coast of Newfoundland, part of modern Canada.

L'Anse aux Meadows consisted of eight buildings of turf (sod) and wood, in both materials and style identical to many in Greenland. One building was a hall large enough to hold 80 people. There was also an iron smithy, a carpenter shop, and a place to repair boats. There were 99 broken iron nails, a complete nail, a bronze pin, a glass bead, a knitting needle, and a spindle--none of these likely artifacts for a contemporary Native American Canadian village. A radiocarbon date on wood gives an age of 1000 AD, in exact agreement with the sagas.

Reconstruction of the Turf and Wood houses at L'Anse aux Meadows [Wikemedia Commons/Creative Commons]

While North America held needed resources for Greenland, the colony did not survive more than 10 years. Native Americans had been in Newfoundland for thousands of years, and while horticulture had not penetrated this far north, large bands of foragers were immediately encountered by the Greenlanders. According to the sagas, the colonists killed 8 of the first 9 Native Americans they met, and the relationship between the two groups went downhill from that point in time. The 5,000 people in Greenland could not support or defend the colony, and the colonists ultimately returned to Greenland. The sagas state that there were other small colonies, but none have been discovered archaeologically.

The Greenlanders continued to sail along the coast of North America for most of the next 300 years, leaving various objects that have been discovered in Native American archaeological sites. These include copper and iron artifacts, spun goat's wool, and a silver penny minted in Norway around 1070, pierced to use as an ornament.

Meanwhile back in Greenland, things started to deteriorate. When the Vikings arrived in Greenland, the warmer climate made growing hay possible, and the limited woodlands were burned to increase pastureland. Grazing prevented the forest from regenerating, a story told via pollen analysis of lake sediments. Wood became very scarce, though needed for building, for various wooden artifacts, for boats, and for smelting iron (which was available in Greenland but could not be extracted or worked without wood). Eventually the only source of wood was Norway and North America. The Greenlanders made annual boat trips north along the west side of Greenland for seals and walrus, the latter primarily for the ivory trade with Europe. (Arab expansion had blocked the normal African and Indian trade routes in ivory.) The ivory trade with Norway often brought back luxury items for the Church and for the upper class, rather than food, wood and iron. Meanwhile, the Greenlanders did not develop good relations with the Inuit; one captured Inuit was poked full of holes to see how much blood he contained. The Greenlanders did not adopt the Inuit's superior umiak and kayak water transportation, made of skin rather than scarce wood. It may have been the shortage of wood which made trips to North America ultimately impossible.

Sometime before 1300 AD, what has been called the "Little Ice Age" started, with an annual drop in temperatures that lasted into the early 1800's. With little hay for the animals, and fewer and ultimately no ship visits from Norway, along with hostile interactions with the Inuit, the Greenlanders began to slowly starve to death.

The smaller of the two Greenland settlements has been excavated. In one more remote farmhouse, the skeleton of a 25 year old man was found on the floor of the house, apparently because nobody was left to bury him. (Radiocarbon dates on his bones indicate he died in 1275 AD.) In the village, many wooden and iron artifacts remain, which would have been taken had people merely moved. In the most recent garbage dump, small bird and rabbit bones were found, food which would not have been eaten if there were alternatives. A newborn calf and lamb had also been eaten, along with several dogs (the Vikings did not normally eat their dogs), and there were indications that all cattle had been slaughtered and eaten down to their toe bones.

In the larger of the two settlements, people survived for a while longer, though the site has not been excavated and details are unknown. Norway sent fewer and fewer ships, partly because of the increase in sea ice due to the "Little Ice Age", and partly due to the fact that in 1349-1350 over 50% of Norway's people (and 1/3 of the population of Europe, some 25 million people) died of the Black Death, or Bubonic Plague. [The Plague was carried by a rat flea, and was probably introduced into Europe and much of western Asia by the Mongols. More on them later.] The last ship returned from Greenland in 1410. No ships visited Greenland again for over 150 years, until an English ship landed in1576; it found only the Inuit, who had adapted well to the climatic change.