THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

Geography 101

ToC

VALLEYS

Landslides

Patterns

Erode

Deposit

Hawai'i

Fluvial Landforms by Erosion

|

|

BOX 1 |

Fluvial (water-related) processes create landforms both by erosion of the solid Earth and by deposition of the material broken loose and carried downstream. As mentioned earlier, the energy for erosion by water comes from sunlight. Sunlight energy evaporates water from the surface and drives winds that lift it to higher elevations where it returns to the surface as precipitation. The work of erosion is powered by that potential energy as water moves downhill on its journey back to the ocean.

When streams flow over the surface, they break down solid material in many ways. First, hydraulic action, the force of the water itself, attacks weakness in the bedrock and pries loose mineral bits. Second, the material carried along by the stream itself rolls and bounces along the surface loosening rock by abrasion. Third, chemical reactions in the water dissolve material and further erode the bedrock.

All

of this loosened material, called sediment, is then transported downstream,

some dissolved in solution (called dissolved load),

some suspended in the water giving it a muddy color (called suspended

load), and the larger

pieces bouncing along the streambed (bed load). Have

you ever stood in a fast moving stream? You can feel the

bed load crashing

against your ankles. That continual pummeling is very effective at wearing

away solid bedrock and carving river valleys.

All

of this loosened material, called sediment, is then transported downstream,

some dissolved in solution (called dissolved load),

some suspended in the water giving it a muddy color (called suspended

load), and the larger

pieces bouncing along the streambed (bed load). Have

you ever stood in a fast moving stream? You can feel the

bed load crashing

against your ankles. That continual pummeling is very effective at wearing

away solid bedrock and carving river valleys.

The shape of landforms created by streams, and the characteristics of the streams themselves, depend greatly on the steepness of the gradient. In general, streams follow a typical longitudinal profile with steep gradients in their mountainous upper reaches and diminishing steepness (flatter terrain) in the lower reaches as the stream nears sea level.

The

fastest erosion occurs near the stream head, where the

gradient is steep, the water flows rapidly, and there is little sediment

load for the stream to carry. Slower, or no, erosion

takes places along the flatter areas in the lower reaches of the stream

where the gradient

is slight, the water flows slowly, and most of the stream's energy is

used to carry the higher sediment load.

The

fastest erosion occurs near the stream head, where the

gradient is steep, the water flows rapidly, and there is little sediment

load for the stream to carry. Slower, or no, erosion

takes places along the flatter areas in the lower reaches of the stream

where the gradient

is slight, the water flows slowly, and most of the stream's energy is

used to carry the higher sediment load.

In

the upper reaches of the streams, rapid erosion carves V-shaped

valleys. In extremely steep, young mountains the V-shaped valleys

may give a wild appearance to the terrain called feral relief,

as shown in the photograph of the high Andes. Typically in high mountains,

streams flow in straight channels and

organize into parallel drainage patterns.

In

the upper reaches of the streams, rapid erosion carves V-shaped

valleys. In extremely steep, young mountains the V-shaped valleys

may give a wild appearance to the terrain called feral relief,

as shown in the photograph of the high Andes. Typically in high mountains,

streams flow in straight channels and

organize into parallel drainage patterns.

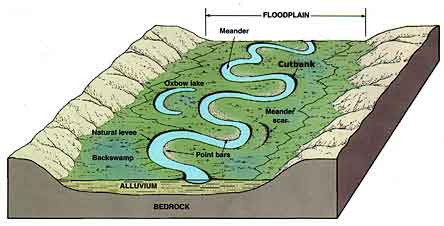

Toward

the lower reaches of the river, the gradient is less steep and streams

form meandering channels that wander back and forth

widening their valleys into flat-bottomed floodplains.

The meanders continuously move as the river cuts into its banks

on the outside of the meander curve, producing a steep cutbank.

As the meander extends in the direction of the cutbank, point

bars form

on the inside of the curved channel.

Toward

the lower reaches of the river, the gradient is less steep and streams

form meandering channels that wander back and forth

widening their valleys into flat-bottomed floodplains.

The meanders continuously move as the river cuts into its banks

on the outside of the meander curve, producing a steep cutbank.

As the meander extends in the direction of the cutbank, point

bars form

on the inside of the curved channel.

Eventually,

as the meander becomes larger and more exaggerated, it will be cut off

by the formation of a new, shorter

section of channel, stranding a small body of water called an oxbow

lake. The oxbow lake eventually fills with sediment and vegetation

leaving only a meander scar.

Eventually,

as the meander becomes larger and more exaggerated, it will be cut off

by the formation of a new, shorter

section of channel, stranding a small body of water called an oxbow

lake. The oxbow lake eventually fills with sediment and vegetation

leaving only a meander scar.

In

addition to straight and meandering channels, a third pattern forms when

a streambed is choked with sediment, typically from glacial meltwater. When the sediment load is greater than the stream's

ability to move it, the runoff

intertwines along the constantly changing streambed in a braided

channel.

In

addition to straight and meandering channels, a third pattern forms when

a streambed is choked with sediment, typically from glacial meltwater. When the sediment load is greater than the stream's

ability to move it, the runoff

intertwines along the constantly changing streambed in a braided

channel.

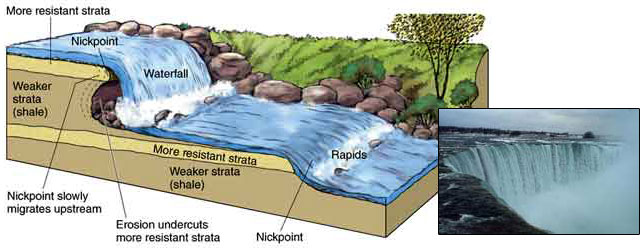

One final fluvial landform created by erosion that should be mentioned is a nickpoint. Nickpoints are breaks in the stream gradient where either waterfalls or steep rapids form. This happens in areas where bedrock consists of layers with different resistances to erosion, as shown below. At waterfalls, tumbling water excavates softer rock at the base, eventually leading to a continual series of small collapses by the more resistant surface rock. In this way, the nickpoint moves slowly upstream. Perhaps the most famous nickpoint is Niagara Falls, which is moving upstream at about 1.2 meters (4 feet) per year.