THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

Geography 101

ToC

EROSION

Wind

Waves

Coasts

Glaciers

Coastal Landforms

|

|

BOX 1 |

Waves release tremendous energy at the world's coastlines. The continual assault shapes a number of distinct landforms, both erosional and depositional.

Erosion

When

waves meet solid land faces, they cut into the land quickly by chemical

erosion, abrasion by loose rocks, and hydraulic

action of the water itself. This produces

notched coastlines and flat offshore terraces, as shown in the diagram.

The focus

of wave

action

grooves a wave-cut

notch, which continually undercuts the overlying rock. The resulting

collapses leave vertical sea cliffs. When you see sea

cliffs, remember that an offshore, flat, wave-built

terrace usually accompanies them.

When

waves meet solid land faces, they cut into the land quickly by chemical

erosion, abrasion by loose rocks, and hydraulic

action of the water itself. This produces

notched coastlines and flat offshore terraces, as shown in the diagram.

The focus

of wave

action

grooves a wave-cut

notch, which continually undercuts the overlying rock. The resulting

collapses leave vertical sea cliffs. When you see sea

cliffs, remember that an offshore, flat, wave-built

terrace usually accompanies them.

Occasionally,

the rapid retreat of the coastline by wave erosion may cut a sea

arch or leave a small island of more resistant

rock called a sea stack. Both of these landforms are

common in Hawai'i. O'ahu, for example, has dozens of offshore sea stacks,

such as the Mokulua Islands shown in the photograph.

Occasionally,

the rapid retreat of the coastline by wave erosion may cut a sea

arch or leave a small island of more resistant

rock called a sea stack. Both of these landforms are

common in Hawai'i. O'ahu, for example, has dozens of offshore sea stacks,

such as the Mokulua Islands shown in the photograph.

Erosional

landforms such as these are common on young islands, such as in Hawai'i

and Japan, and on coasts being uplifted tectonically, such as the west coast of North America.

Erosional

landforms such as these are common on young islands, such as in Hawai'i

and Japan, and on coasts being uplifted tectonically, such as the west coast of North America.

While

sea cliffs and wave-built terraces develop at the coastline, these features

can be found both below and above present day sea level. This occurs

through changing sea levels and subsidence or uplift of the land itself. Overall,

the Islands are slowly sinking and old shoreline features can be found

hundreds of meters below the ocean surface. The photograph shows UH geologist

Tony Clark diving on a submerged notch

in shallow water off O'ahu.

While

sea cliffs and wave-built terraces develop at the coastline, these features

can be found both below and above present day sea level. This occurs

through changing sea levels and subsidence or uplift of the land itself. Overall,

the Islands are slowly sinking and old shoreline features can be found

hundreds of meters below the ocean surface. The photograph shows UH geologist

Tony Clark diving on a submerged notch

in shallow water off O'ahu.

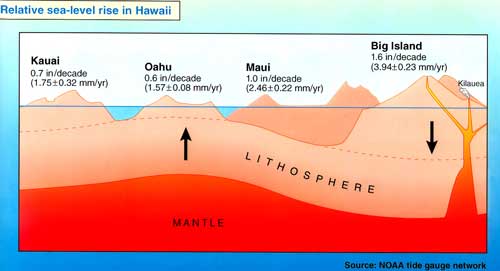

On the other hand, a drop in sea level over the past few thousand years has stranded some old shorelines well above present-day sea level. The Ewa Plain on O'ahu is an old wave-built terrace covered with coral that was exposed by dropping sea level and flexure in the lithosphere, as shown in the diagram below. Note in the diagram that flexure in the lithosphere, caused by the great weight of the Big Island, counteracts the normal sinking motion of O'ahu.

Deposition

Material

broken loose by erosion grinds into smaller and smaller pieces. Currents

often carry away the smallest bits (clay

and silt) in suspension leaving sand and gravel

deposits. These deposits are in constant motion, moving both toward and

away from shore through wave action and laterally along the coastline

by longshore

currents. Heavy

waves,

for

example,

will

drag

sand offshore

and steepen the beach face, while light wave action brings sand onshore

and flattens the beach face. Longshore currents form when waves approach

the coast at an angle. The oblique wave action sets up a current that

carries material,

called littoral drift, slowly along the shoreline.

Material

broken loose by erosion grinds into smaller and smaller pieces. Currents

often carry away the smallest bits (clay

and silt) in suspension leaving sand and gravel

deposits. These deposits are in constant motion, moving both toward and

away from shore through wave action and laterally along the coastline

by longshore

currents. Heavy

waves,

for

example,

will

drag

sand offshore

and steepen the beach face, while light wave action brings sand onshore

and flattens the beach face. Longshore currents form when waves approach

the coast at an angle. The oblique wave action sets up a current that

carries material,

called littoral drift, slowly along the shoreline.

Look at the photograph of part of Waikiki Beach. The waves approach the shore from right to left. This transports beach sand to the left, causing it to build into triangular beaches when it encounters groins and the rectangular Natatorium extending offshore.

Beaches are

the most familiar depositional landform of coasts. In Hawai'i, the lighter

colored sand is composed

mainly of ground-up coral reef and the shells of other marine animals.

Mineral material, mostly ground-up basalt, makes up the darker sand particles.

On the Big Island, areas with little coral produce black sand

beaches. Near South Point a few unusual green sand beaches

have formed, dominated by the mineral olivine.

Beaches are

the most familiar depositional landform of coasts. In Hawai'i, the lighter

colored sand is composed

mainly of ground-up coral reef and the shells of other marine animals.

Mineral material, mostly ground-up basalt, makes up the darker sand particles.

On the Big Island, areas with little coral produce black sand

beaches. Near South Point a few unusual green sand beaches

have formed, dominated by the mineral olivine.

The

construction of sea walls, groins, breakwaters, and other artificial

barriers interrupts

the natural movement of sand

and dissipation of wave energy, and can cause severe beach erosion.

On O'ahu, for example, kilometers of beach have been lost to erosion

during

the past century. To reclaim these areas, beach

restoration by nourishment is

becoming increasingly accepted. Beach nourishment simply

means artificially adding sand to restore the original beach. Waikiki

and Lanikai beaches have been replenished many times since

the

1930's.

The

construction of sea walls, groins, breakwaters, and other artificial

barriers interrupts

the natural movement of sand

and dissipation of wave energy, and can cause severe beach erosion.

On O'ahu, for example, kilometers of beach have been lost to erosion

during

the past century. To reclaim these areas, beach

restoration by nourishment is

becoming increasingly accepted. Beach nourishment simply

means artificially adding sand to restore the original beach. Waikiki

and Lanikai beaches have been replenished many times since

the

1930's.

Bay-mouth bars are another common depositional feature in Hawai'i. These sand and river-sediment deposits completely block the mouth of streams, but may open up in times of heavy stream flow or high waves. Perhaps the best known bay-mouth bar in Hawai'i closes the Waimea River on O'ahu. The bar blocking the river mouth is so stable that it was used as a temporary road when the Kamehameha Highway (background) closed due to rock slides in 2000.

In

other areas, spits, tombolos, and barrier islands may form. Spit refers

to any sand deposit that juts out into the ocean or partially closes

a river mouth. If the spit connects

an offshore island,

it is called a tombolo.

In

other areas, spits, tombolos, and barrier islands may form. Spit refers

to any sand deposit that juts out into the ocean or partially closes

a river mouth. If the spit connects

an offshore island,

it is called a tombolo.

Barrier islands are enormous deposits of sand and other sediments that form offshore and parallel to long coastlines. They are characteristic of slowly subsiding coastlines, such as the east coast of North America, as shown in the satellite image of North Carolina's coastline. The barrier island is the thin outer line to the right in the image.

These sinking coastlines become deeply embayed as river mouths slowly subside below sea level. The barrier island has the effect of straightening the coastline's face to seaward.

Reefs

Coral

reefs are an example of how biological activity can dramatically shape

a coastline. The corals themselves are small

marine animals that build calcium carbonate (limestone) enclosures and

grow in tropical waters. While the animal itself may be small, they cluster

in

huge colonies.

The

world's

largest

biological

structure is the Great Barrier Reef, a coral community

over 2300 km (1400 mi) in length.

Coral

reefs are an example of how biological activity can dramatically shape

a coastline. The corals themselves are small

marine animals that build calcium carbonate (limestone) enclosures and

grow in tropical waters. While the animal itself may be small, they cluster

in

huge colonies.

The

world's

largest

biological

structure is the Great Barrier Reef, a coral community

over 2300 km (1400 mi) in length.

The

importance of coral growth in the tropics cannot be overstated as coral

islands make up the majority of islands in

many tropical oceans. The process begins when an island emerges from

the ocean, generally through volcanism. First, a fringing reef grows

touching the island shoreline. All reefs in the main Hawaiian Islands

are this type, including this example at Kaunakakai, Moloka'i.

The

importance of coral growth in the tropics cannot be overstated as coral

islands make up the majority of islands in

many tropical oceans. The process begins when an island emerges from

the ocean, generally through volcanism. First, a fringing reef grows

touching the island shoreline. All reefs in the main Hawaiian Islands

are this type, including this example at Kaunakakai, Moloka'i.

When the island growth phase is over, it begins to slowly sink into the lithosphere under its own enormous weight. The Big Island, for example, is sinking at about 4 mm/year. As the island's surface area diminishes, the coral continues growing in its original position, getting farther and farther from the receding shoreline and forming a barrier reef. Bora Bora, in the Society Islands, is a beautiful example of this stage of reef growth.

Eventually,

the original basalt island sinks completely below sea level, leaving

only the tip of an ever-thickening crust of

reef above the waves. This creates a low-lying ring of coral-sand

islands surrounding a central lagoon called an atoll.

Eventually,

the original basalt island sinks completely below sea level, leaving

only the tip of an ever-thickening crust of

reef above the waves. This creates a low-lying ring of coral-sand

islands surrounding a central lagoon called an atoll.

Most of the northwest Hawaiian Islands,

including Kure shown here, are

atolls. They are the only visible evidence remaining

of long dead volcanic mountains.

Most of the northwest Hawaiian Islands,

including Kure shown here, are

atolls. They are the only visible evidence remaining

of long dead volcanic mountains.

Eventually, the atoll will move into water too cold to support coral growth and sink beneath the waves leaving an underwater, flat-topped mountain called a guyot. The Hawaiian Emperor chain of underwater mountains is composed of guyots and other seamounts.