THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

Geography 101

ToC

EROSION

Wind

Waves

Coasts

Glaciers

Waves

|

|

BOX 1 |

Land and ocean meet at the world's coastlines. Waves and currents batter and chip away the solid surface, then redistribute the broken pieces to create beaches, sandbars and other deposits.

Once again, sunlight provides the energy for coastal erosion and deposition. Solar heating of Earth's surface creates air pressure differences that drive the winds. Friction between the ocean surface and wind drives ocean surface currents and creates waves. The energy stored in waves and currents is then released at coastlines as waves break upon the shoreline.

Waves

Waves

The process begins with the creation of waves. When the wind begins to blow, friction produces small ripples on the water surface, called capillary waves. The water molecules set in motion by wind begin to travel in small circles that we see at the surface as waves. This circular motion continues below the surface to a depth of about ½ the wavelength (defined below).

As

wind speed and duration increases, the wave height increases. The

size of the resulting waves depends on wind speed,

how long the wind blows (duration), and over what distance

the wind blows (fetch). An increase in any of these

variables will cause a corresponding increase in wave height up to a

maximum size.

As

wind speed and duration increases, the wave height increases. The

size of the resulting waves depends on wind speed,

how long the wind blows (duration), and over what distance

the wind blows (fetch). An increase in any of these

variables will cause a corresponding increase in wave height up to a

maximum size.

When

waves travel beyond the windy area in which they were created, they

smooth into rounded

shapes called swells.

Swells can travel enormous distances and deliver energy given them by

the wind to coastlines thousands of kilometers away.

When

waves travel beyond the windy area in which they were created, they

smooth into rounded

shapes called swells.

Swells can travel enormous distances and deliver energy given them by

the wind to coastlines thousands of kilometers away.

When waves travel, they are described by their height, wavelength and period as shown in the diagram. The distance from crest to crest, or from trough to trough, is called the wave length and the vertical distance between the crest and trough is the wave height. The time it takes to travel a distance of one wavelength is the wave period.

As

noted above, when waves leave their generating area, they become swells

as their wave height decreases

and wave length and period increase. A typical swell producing 3 meter (10 foot)

surf on O'ahu's north shore might have a period of 18 seconds and a wave

height of 2.4 meters (8 feet). In Hawai'i, most winter swells are generated in the

North Pacific Ocean and most summer swells are generated in the South

Pacific.

As

noted above, when waves leave their generating area, they become swells

as their wave height decreases

and wave length and period increase. A typical swell producing 3 meter (10 foot)

surf on O'ahu's north shore might have a period of 18 seconds and a wave

height of 2.4 meters (8 feet). In Hawai'i, most winter swells are generated in the

North Pacific Ocean and most summer swells are generated in the South

Pacific.

Interestingly, the larger the wave, the faster it travels. A wave train with a period of 10 seconds, for example, travels at about 56 kilometers per hour (35 mph). A northwest swell with a period of 20 seconds, however, travels twice as fast at 112 kilometers per hour (70 mph).

When

a wave or swell approaches shore, friction with the ocean bottom causes

the wave to steepen and grow in height until it breaks as surf. In Hawai'i,

something of a controversy arose regarding surf height reporting.

Local

custom

dictates

that the

approximate

height

of the back of a breaking wave (1/2 to 2/3 the face height) be

reported as the surf height. Internationally, however, the full wave

face height is reported,

as shown in the diagram. The National Weather Service reports the standard

wave face height in their surf forecast, but some agencies, such

as the Surf Network, include the local custom of

2/3

wave face. So, when reading the surf forecast, be sure to check which

method is used.

When

a wave or swell approaches shore, friction with the ocean bottom causes

the wave to steepen and grow in height until it breaks as surf. In Hawai'i,

something of a controversy arose regarding surf height reporting.

Local

custom

dictates

that the

approximate

height

of the back of a breaking wave (1/2 to 2/3 the face height) be

reported as the surf height. Internationally, however, the full wave

face height is reported,

as shown in the diagram. The National Weather Service reports the standard

wave face height in their surf forecast, but some agencies, such

as the Surf Network, include the local custom of

2/3

wave face. So, when reading the surf forecast, be sure to check which

method is used.

Tsunami

The

largest waves are not generated by wind, but by the same forces

that produce earthquakes. Sudden movements in Earth's

crust, caused by faulting, volcanoes or landslides, can displace huge

volumes of water and generate tremendous wave energy. This energy travels

as

a gigantic

swell,

with

a very long

wave

period, but only a moderate height. The wave is indistinguishable at

sea, but once it reaches land, it can build to great height.

The

largest waves are not generated by wind, but by the same forces

that produce earthquakes. Sudden movements in Earth's

crust, caused by faulting, volcanoes or landslides, can displace huge

volumes of water and generate tremendous wave energy. This energy travels

as

a gigantic

swell,

with

a very long

wave

period, but only a moderate height. The wave is indistinguishable at

sea, but once it reaches land, it can build to great height.

Because they have such long periods, tsunami waves can travel extremely rapidly across deep oceans. At 4500 meters (15,000 feet) depth, they travel at about 800 kph (500 mph), as fast as a jet aircraft. At that speed, they can cross an ocean in just a few hours, as shown in the travel time map. This characteristic allows little time to warn residents of an impending event in exposed, less-developed areas. A common misconception regarding tsunamis is that only a single giant wave comes ashore. In reality, several large waves may strike several minutes apart. Many people have died returning to a waterfront after the first tsunami wave struck, only to be swept away when a second large wave came ashore.

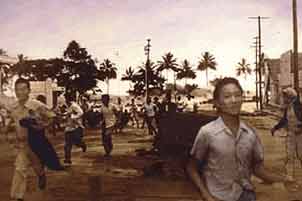

Hawai'i has experienced many tsunami events. The US Army Corps of Engineers estimates that damaging tsunamis have struck Hawai'i every four or five years on average, although less frequently in recent years. Hilo has become the informal tsunami capital of the world due to repeated tsunami disasters. In 1946, a wave generated in Alaska struck, killing 159 and destroying the Hilo waterfront. It also swept the peninsula at Laupahoehoe, Big Island, leveling a small school and drowning 16 children and 4 teachers. In 1960, disaster struck again when a wave generated near Chile once again leveled the Hilo bayfront, killing 61 people. Today, the entire waterfront area has been replaced with extensive parks and a high berm carrying the Bayfront Highway designed to minimize future tsunami damage.

|

|

|

People flee 1946 tsunami in Hilo |

1946 tsunami approaches man on pier |