THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

Geography 101

ToC

CLOUDS

Evap

Humidity

Stability

Condense

Clouds

Condensation

When air cools to the dew point, water vapor in the air condenses into liquid water. This phenomenon is quite common. Water condenses onto the surface of cold cans taken from a refrigerator or icebox. When the ground cools at night, water vapor condenses to form dew. Water vapor in the hot air rising from your morning coffee cools and condenses to form small, wispy clouds. And of course, condensation in the atmosphere produces clouds and fog.

|

|

BOX 1 |

Cloud Condensation Nuclei

Condensing

water requires a solid surface to condense onto. At the surface,

dew forms on just about any cold object. In

the air, solid particles are called cloud condensation nuclei,

or CCNs. The atmosphere always contains these tiny

particles, including sea salt, pollen, dust, pollutants,

volcanic ash, and dozens of compounds in smoke. Most CCNs are less

that 1 micrometer in size, with the exception of a few giant

ones, such as sea salt.

Condensing

water requires a solid surface to condense onto. At the surface,

dew forms on just about any cold object. In

the air, solid particles are called cloud condensation nuclei,

or CCNs. The atmosphere always contains these tiny

particles, including sea salt, pollen, dust, pollutants,

volcanic ash, and dozens of compounds in smoke. Most CCNs are less

that 1 micrometer in size, with the exception of a few giant

ones, such as sea salt.

Some CCN's are more efficient than others. Sea salt for example, can begin to adsorb liquid water even before the air cools to the dew point. This may give coastal air a hazy appearance as particles grow in size and scatter white light. Ever notice how deep blue the sky looks after a rainfall? That's because rainfall scours CCNs out of the atmosphere and reduces Mie scattering (discussed in Chapter 2 -> Scattering). Natural processes quickly replace them, however.

Cloud Droplets

Cloud Droplets

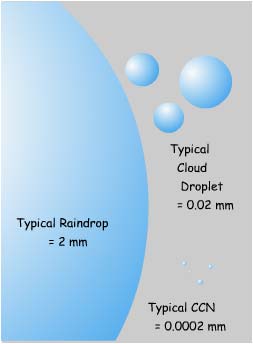

At the dew point, water condenses onto CCNs in the atmosphere and cloud droplets begin to grow, eventually reaching 10 to 20 micrometers in diameter. At this size they are easily held aloft by updrafts. If a droplet does fall below the cloud layer, it quickly evaporates.

A cloud may contain about a million droplets per cubic meter depending on the number, size, and properties of the available CCNs. In general, a large number of tiny CCNs produces a large number of tiny cloud droplets. Fewer, but larger, CCNs produce fewer, but larger, droplets. Larger droplets are usually more efficient at producing rainfall.

This simple property may be responsible for below normal rainfall on the Big Island's Kona coast since 1982 when Kilauea came to life. The volcano puts out huge quantities of CCNs, flooding the downwind "airshed" of south Kona with small atmospheric particles, which we see as "vog." This produces vast numbers of tiny cloud droplets, which are not efficient at producing rainfall.

Precipitation

One of the largest

raindrops ever measured was near Hilo.

It was 8 mm in diameter. One of the largest

raindrops ever measured was near Hilo.

It was 8 mm in diameter. |

Cloud droplets may eventually join together to become one of the many forms of precipitation that falls from the sky. Raindrops form by collision and coalescence of cloud droplets, i.e. they collide with each other and merge into a larger drop. As a drop grows, it falls faster than surrounding smaller droplets and scoops them up onto its lower surface. The expanding water drops fall to earth when they are either too heavy to be lifted by updrafts or they enter a downdraft. A typical raindrop might grow to 2 mm or so in diameter, although size varies greatly, and contain a million cloud droplets. In general, a mixture of different cloud drop sizes promotes raindrop growth because they fall at different speeds and are more likely to collide. A large number of very small droplets would be less likely to form rain, as collisions are less likely.

Snowflakes form differently. Ice crystals need surfaces to freeze onto called ice forming nuclei, just as cloud droplets need CCNs to condense onto. Good ice forming nuclei have a structure similar to frozen water, such as the mineral kaolinite, which is a common airborne particle. Once the tiny ice crystal forms, it grows by: 1) transfer of water from liquid drops to ice crystals by evaporation and condensation (or sublimation), and 2) liquid cloud droplets freezing on contact.

Artificial cloud

seeding relies on this process. Ice forming

nuclei, generally

silver iodide, are spread into cold clouds to provide particle surfaces that initiate

freezing. Although ice crystals form initially, they may fall as cold

rain after melting on their descent to the surface.

Artificial cloud

seeding relies on this process. Ice forming

nuclei, generally

silver iodide, are spread into cold clouds to provide particle surfaces that initiate

freezing. Although ice crystals form initially, they may fall as cold

rain after melting on their descent to the surface.

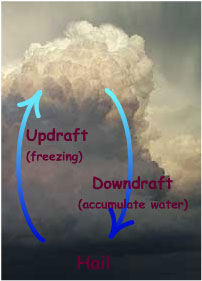

Hail forms by cycling though updrafts and downdrafts in deep thunderstorm clouds. In the upper part of the storm, raindrops freeze into ice balls, which then descend in downdrafts accumulating a surface layer of water as they fall, only to be carried upward again by updrafts where the accumulated water freezes into a new ice layer. In this way, the hailstone grows as concentric frozen shells; as many as 22 layers have been counted in an individual hailstone.

Hail stories abound. Hail cannons were

popular at the end of the nineteenth century as a hopeful means of warding

off destructive

hail. People filled huge funnels with gunpowder and blasted

them at threatening clouds. The Russians

advanced this concept to the point of exploding rockets in thunderclouds,

reasoning that sound waves would break up hailstones, but this

approach never proved effective. In southern states, like Florida and Texas,

car lots have "hail sales" every summer to sell cars beaten

and dented by uncaring hail storms. The current record hailstone was found in Vivian, South Dakota with a diameter of 20.3 cm (8") and weighing 878 grams (1.936 pounds). The image shows a previous record stone from Coffeyville, Kansas that highlights the internal rings created as the iceball grows by cycling up and down in the thundercloud.

Hail stories abound. Hail cannons were

popular at the end of the nineteenth century as a hopeful means of warding

off destructive

hail. People filled huge funnels with gunpowder and blasted

them at threatening clouds. The Russians

advanced this concept to the point of exploding rockets in thunderclouds,

reasoning that sound waves would break up hailstones, but this

approach never proved effective. In southern states, like Florida and Texas,

car lots have "hail sales" every summer to sell cars beaten

and dented by uncaring hail storms. The current record hailstone was found in Vivian, South Dakota with a diameter of 20.3 cm (8") and weighing 878 grams (1.936 pounds). The image shows a previous record stone from Coffeyville, Kansas that highlights the internal rings created as the iceball grows by cycling up and down in the thundercloud.

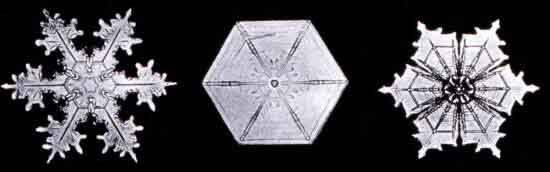

The old saying that no two snowflakes are alike derives from the work of Vermont farmer W.A. Bentley who published a definitive volume of nearly 2500 snowflake photographs in 1931. Three of his snowflakes, captured by taking frozen microscope slides outside into the snow, are shown below. The hexagonal symmetry derives from the molecular shape of water molecules.

"Under the microscope, I found that snowflakes were miracles of beauty; and it seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others. Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated. When a snowflake melted, that design was forever lost. Just that much beauty was gone, without leaving any record behind." Wilson "Snowflake" Bentley, 1925 |