THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

Geography 101

ToC

CLOUDS

Evap

Humidity

Stability

Condense

Clouds

Stability

Individual

clouds may weigh hundreds of tonnes. Why don't they fall out of the sky?

The answer is that updrafts support the individual cloud droplets. Rising air not only supports the cloud,

but causes its formation as well. As air rises, it expands, diffuses

heat energy, and cools. If the air cools to the dew point, water vapor will

condense to form

liquid cloud

droplets. Condensing water releases heat and warms the nascent cloud's interior, helping it grow higher and higher.

Look

at the

cloud

and imagine its interior boiling upward, heated by condensation as it

rises.

|

|

BOX 1 |

Rising air in clouds, then, simultaneously cools by expansion and heats by condensation. The net result is that air inside clouds is warmer than surrounding air on the outside.

The tendency of air to rise or not, called atmospheric stability, helps determine whether clouds will be deep and produce precipitation, or thin with no precipitation, or simply not form at all. If air tends to rise easily, the atmosphere is said to be unstable and deep clouds with precipitation are likely to form. If air tends to resist rising, the atmosphere is said to be stable with accompaning clear skies and dry weather.

The

fundamental principal of cloud formation is fairly simple: warm air rises.

If we fill a balloon with hot air, it will rise, hence the sport of hot

air ballooning. But what if we fill it with air that is the same temperature as the air around it? It will just sit there and not go anywhere,

or maybe even sink and flop over on the ground.

The

fundamental principal of cloud formation is fairly simple: warm air rises.

If we fill a balloon with hot air, it will rise, hence the sport of hot

air ballooning. But what if we fill it with air that is the same temperature as the air around it? It will just sit there and not go anywhere,

or maybe even sink and flop over on the ground.

The same is true of blobs of air, called parcels, in the atmosphere. If they stay warmer than the surrounding air, they keep rising just like the hot air balloon and the atmosphere is said to be unstable. If they are not warmer than the surrounding air, they will resist rising and, if forced to rise somehow, will return to their original altitude. The atmosphere is said to be stable.

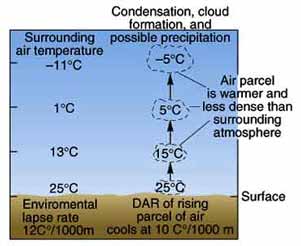

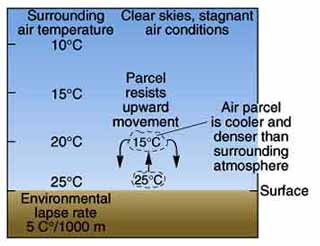

The diagrams below illustrate why air parcels either continue to rise (unstable) or return to their original position (stable) when given an initial push upwards. In each diagram, compare the temperature of the parcel of air with temperature of the surrounding air outside the parcel at each altitude level separately. The Dry Adiabatic Lapse Rate (DALR or DAR) refers to the rate at which a rising parcel of air cools, typically 10° C per kilometer, and the Environmental Lapse Rate (ELR) refers to the actual temperature profile in the atmosphere. Once again, the physical reasoning is pretty straightforward: warm air rises. If the parcel is warmer than the air around it, it will keep rising and deep clouds can form. If not, it will return to its original position and clear skies will prevail.

|

|

Unstable Conditions |

Stable Conditions |

The Environmental Lapse Rate is the key to stability. If it is high , for example, 12° C as shown in the left hand diagram, the air will be unstable. If it is low, for example, 5° C as shown in the right hand diagram, the air will be stable. Any condition that increases the ELR also promotes unstable conditions. An increased ELR is caused by both warming the surface, like on a hot, sunny day, and cooling the upper atmosphere, like radiative cooling of cloud tops. Phenomena that cool the surface, like a cool ocean current, and heat the upper atmosphere, like a temperature inversion, promote stable conditions. Review this paragraph carefully to understand how different conditions affect stability and change the environmental lapse rate.

Typically, the atmosphere is neither absolutely stable nor unstable, but somewhere in between in a state called conditionally unstable. The air can become unstable on the condition that it is forced to rise and cool to the dew point. At the dew point, condensation releases heat into the interior of the newly forming cloud and warms the air parcel. If water continues to condense until the air parcel grows warmer than the surrounding air, it becomes unstable and will continue to grow upwards. It is no accident that cloud tops look like they are boiling; in a sense they are, through heat released by condensation. The natural processes that force air to rise against stability are discussed in the next chapter.

This is probably the most conceptually challenging section in the book. Just remember: air rises if it is warmer than the surrounding air at the same altitude and sinks if it is colder.

Hawai'i

In Hawai'i, the atmosphere is generally stable because of the trade wind inversion (see discussion in Chapter 3 -> Local). Air parcels simply cannot rise though this warm air layer. If you drive up Haleakala or Mauna Kea on a typical trade wind day, you will pass through the cloud layer and emerge into clear skies at around 1800 to 2400 meters (6000 to 8000 feet) elevation where you can look down upon the cloud deck. (A cloud deck is the top of a layer of clouds. A cloud ceiling is the bottom.) Next time you fly inter-island, look for the flat cloud deck that marks the temperature inversion as shown in the view from the top of Haleakala below.