THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

Geography 101

ToC

CLOUDS

Evap

Humidity

Stability

Condense

Clouds

Evaporation

Atmospheric Water Cycle

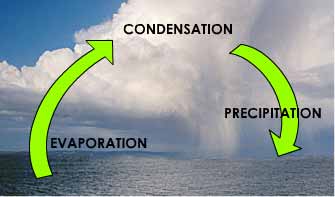

Water enters and leaves the atmosphere fairly rapidly.

On average, a water molecule spends only about 9 days in the air before

returning to Earth as some form of precipitation. This rapid cycling

shifts enormous amounts of heat around the globe, redistributes water

from oceans

to land, and produces our

most spectacular weather.

Water enters and leaves the atmosphere fairly rapidly.

On average, a water molecule spends only about 9 days in the air before

returning to Earth as some form of precipitation. This rapid cycling

shifts enormous amounts of heat around the globe, redistributes water

from oceans

to land, and produces our

most spectacular weather.

Water enters the atmosphere as a gas, water vapor, by evaporation from wet surfaces and through plants. It works its way upward by turbulent mixing (up and down air motion), although it typically does not rise far. Most water vapor stays within a few kilometers of the surface. Over Hawai'i, in fact, 80% of all water vapor resides between sea level and the inversion level of around 2000 meters (6600 feet) altitude. This makes water vapor quite different from other atmospheric gases, which are well mixed throughout the entire atmosphere. Even tens of kilometers above the surface, nitrogen, oxygen, and argon are still found in the same proportions as at sea level, while water is not.

|

|

BOX 1 |

When air cools, water condenses into the droplets and ice crystals that make up clouds. Condensing water releases an enormous amount of heat into the atmosphere. Recall that water absorbs heat from the surface when it evaporates. (See Chapter 3 -> Balance). So, the process of evaporation and condensation transfers heat from the surface to the atmosphere and this heat energy is stored in the motion of the water vapor molecules. This heat transfer provides energy to the atmosphere that drives Earth's weather systems, from the mightiest hurricane to the smallest raincloud.

When clouds grow deep enough, they produce precipitation and water returns to the surface. By that time, an individual water molecule may have traveled many thousands of kilometers on the wind, falling far from its source area. Precipitation, by the way, refers to all forms of liquid and solid water that fall from the sky, including rain, snowflakes, sleet, and hail.

Evaporation

Evaporation refers to the phase change of water from liquid to gas. When this happens through plant leaves, it is called transpiration. In the lexicon of scientists, open water evaporates, plant leaves transpire. Physically, the prcess is the same, but plants have control over the rate and amount of water evaporated.

About 86% of atmospheric water vapor enters the air by evaporation from oceans and especially from surfaces of the warmest

tropical oceans. In areas of highest evaporation, the loss of fresh

water from the ocean surface concentrates salt and increases

the local salinity. A typical value for the highest evaporation

rate from the warmest ocean surface would be around 2.5 meters (8 feet) per year.

In polar areas, the evaporation rate is far less, approaching zero over the

frozen Arctic Ocean. The pattern of evaporation from the ocean surface

is shown in the image (darker is more). Notice the highest values are

off the east coasts of Asia and North America, where currents carry warm

water north into cooler latitudes. The Hawaiian Islands area, in the

center of the map, has one of the globe's highest evaporation rates as

well, and hence, relatively high ocean surface salinity.

About 86% of atmospheric water vapor enters the air by evaporation from oceans and especially from surfaces of the warmest

tropical oceans. In areas of highest evaporation, the loss of fresh

water from the ocean surface concentrates salt and increases

the local salinity. A typical value for the highest evaporation

rate from the warmest ocean surface would be around 2.5 meters (8 feet) per year.

In polar areas, the evaporation rate is far less, approaching zero over the

frozen Arctic Ocean. The pattern of evaporation from the ocean surface

is shown in the image (darker is more). Notice the highest values are

off the east coasts of Asia and North America, where currents carry warm

water north into cooler latitudes. The Hawaiian Islands area, in the

center of the map, has one of the globe's highest evaporation rates as

well, and hence, relatively high ocean surface salinity.

Over land, the situation is much more complex. Water evaporates from open water of course, but continuously wet surfaces cover very little of Earth's land area. Most water entering the atmosphere from land surfaces, about 14% of the global total, takes place through plant leaves.

Plants

can control both the rate and amount of water available for evaporation. Roots extract water from below the surface that is then conveyed to the leaves where it evaporates through

openings called stomata (plural of stoma),

a process called transpiration.

The green image shows an electron microscope view of an 'ohia stoma.

The width and depth of the root systems, then, helps to determine the amount of water available for transpiration from land areas. Overall, plant roots can

suck an enormous

amount of water from the ground. Researchers estimate that, for

the Pearl Harbor-Honolulu aquifer in central O'ahu, evaporation and transpiration

return about 40% of all rain falling in the watershed back

to the atmosphere. Plants can also limit the rate of transpiration by partially or completely closing their stomata. In dry areas, they often use this strategy to conserve water.

Plants

can control both the rate and amount of water available for evaporation. Roots extract water from below the surface that is then conveyed to the leaves where it evaporates through

openings called stomata (plural of stoma),

a process called transpiration.

The green image shows an electron microscope view of an 'ohia stoma.

The width and depth of the root systems, then, helps to determine the amount of water available for transpiration from land areas. Overall, plant roots can

suck an enormous

amount of water from the ground. Researchers estimate that, for

the Pearl Harbor-Honolulu aquifer in central O'ahu, evaporation and transpiration

return about 40% of all rain falling in the watershed back

to the atmosphere. Plants can also limit the rate of transpiration by partially or completely closing their stomata. In dry areas, they often use this strategy to conserve water.

The

evaporation rate from any surface, including plant stomata, depends on the amount of energy

available from sunlight, the relative humidity, and the wind speed.

Think of drying your laundry on a clothesline. It will dry faster in

the sun

than in the shade, faster on a low humidity day

than on a high humidity day, and faster on a windy day than a calm

day. This holds true over Earth's surface as well. The amount of sunlight

energy is especially important, as is evident in the ocean evaporation

map.

In general, the warm, sunny subtropics have higher

evaporation rates than cloudy equatorial or colder midlatitude and polar

areas.

The

evaporation rate from any surface, including plant stomata, depends on the amount of energy

available from sunlight, the relative humidity, and the wind speed.

Think of drying your laundry on a clothesline. It will dry faster in

the sun

than in the shade, faster on a low humidity day

than on a high humidity day, and faster on a windy day than a calm

day. This holds true over Earth's surface as well. The amount of sunlight

energy is especially important, as is evident in the ocean evaporation

map.

In general, the warm, sunny subtropics have higher

evaporation rates than cloudy equatorial or colder midlatitude and polar

areas.

In

Hawai'i, many projects have studied

evaporation and transpiration rates from various land surfaces. It

is a highly elusive thing to measure. The standard instrument is not

very

sophisticated;

just a 1.22 meter (4 feet) diameter steel tub called an evaporation pan,

as shown in the photo. A technician records the water level and refills

the pan at regular intervals.

In

Hawai'i, many projects have studied

evaporation and transpiration rates from various land surfaces. It

is a highly elusive thing to measure. The standard instrument is not

very

sophisticated;

just a 1.22 meter (4 feet) diameter steel tub called an evaporation pan,

as shown in the photo. A technician records the water level and refills

the pan at regular intervals.

Local evaporation studies have mostly focused on water requirements for crops and evaporation from Hawaiian watersheds in a attempt to model recharge to various aquifers.