THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

Geography 101

ToC

WEATHER

Lifting

Air Mass

Fronts

Hurricane

Hawaii

Fronts & Midlatitude Cyclones

|

|

BOX 1 |

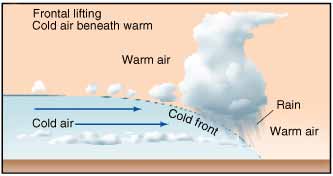

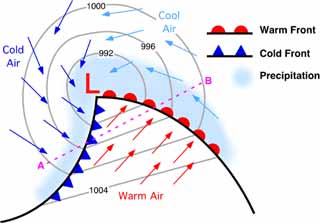

Fronts cause more severe weather than any of the other lifting forces. When air masses collide, they do not readily mix, but instead form a boundary, or front. Named during World War I, they were identified in military terms. If the cold air mass is pushing back the warm air mass (thus, winning), it forms a cold front. If the warm air mass is advancing on a cold air mass, it forms a warm front.

Cold Front

Cold fronts form when a cold air mass, either cP or mP, bulldozes into a warm air mass, pushing it back and forcing the warmer air to rise. Typically these are fast moving fronts in which the warm air is lifted rapidly, almost always producing at least a cloud band. If the warm air has a high moisture content, clouds can grow explosively producing thunderstorms and squall lines, even spawning tornadoes.

Cold Front Forecast"Today expect warm and humid conditions, light winds from the southwest, and scattered cloudiness. Tonight, a cold front is expected to pass with temperature dropping, winds increasing and veering to the west, pressure dropping, with brief thunderstorms, lightning, and heavy rain. Tomorrow, expect clear skies, higher pressure, cool dry air, and strong winds from the northwest." |

|

Tracking

fronts is probably the midlatitude weather person's greatest forecasting

tool, because the sequence of weather

change is fairly predictable. Look at the diagram above and imagine

the cold front moving to the right. A person would first be in the warm

(pink)

sector,

then

under the clouds (the front itself), then in the cold (blue) sector.

The forecast might be something like the one given above.

Tracking

fronts is probably the midlatitude weather person's greatest forecasting

tool, because the sequence of weather

change is fairly predictable. Look at the diagram above and imagine

the cold front moving to the right. A person would first be in the warm

(pink)

sector,

then

under the clouds (the front itself), then in the cold (blue) sector.

The forecast might be something like the one given above.

Cold fronts are highly visible on satellite imagery as they produce a thick stripe of clouds that sweeps across the face of the Earth, moving from west to east. Fast moving cold fronts occasionally spawn a continuously advancing band of intense thunderstorms called a squall line, as shown in the Space Shuttle image.

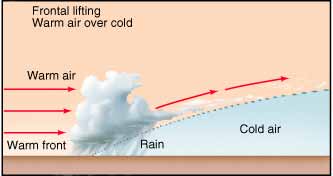

Warm Front

Warm fronts are generally much less intense than cold fronts and occur where a warm air mass (cT or mT) gradually pushes back a higher density cold air mass. The temperature difference across the front is less, the speed is slower, the slope of the boundary is shallower, and the speed of lifting is lower. Note that in both warm and cold fronts, the warm air overlies the cold air.

Warm Front Forecast"Today expect mild conditions, with cool air, moderate to dry humidity, and easterly winds. Tonight, a warm front is expected to pass with temperatures slowing rising, a brief wind increase, increasing cloudiness and a chance of light rain. Tomorrow, expect partially cloudy skies, and warm humid weather with winds veering to the south. |

|

Stationary and Occluded Fronts

A stationary front forms when the boundary between

air masses is not moving at all. An occluded front forms

when a cold front overtakes a warm front and lifts the warm air mass

completely off of the surface as shown in the diagram. This generally

marks the end of the frontal system because the warm air/cold air boundary

at the surface no longer exists.

A stationary front forms when the boundary between

air masses is not moving at all. An occluded front forms

when a cold front overtakes a warm front and lifts the warm air mass

completely off of the surface as shown in the diagram. This generally

marks the end of the frontal system because the warm air/cold air boundary

at the surface no longer exists.

Weather Symbols

Common Weather Symbols |

|||

|

Cold Front |

|

Stationary Front |

|

Warm Front |

|

Occluded Front |

|

Low Pressure |

|

Hurricane |

|

High Pressure |

|

Thunderstorm |

Warm fronts, cold fronts, and many other weather phenomena are represented on maps with internationally recognized symbols, a few of which are shown in the table. At the surface, a cold air mass is typically a high pressure center (hence the blue color) and a low pressure center is warm (so shown as red). The triangles and half circles of the cold and warm front symbols show the direction of motion of the front -- the front moves in the direction the symbols are pointing. If the symbols' orientation in the table were shown a weather map, it would indicate that both the cold and warm fronts were moving toward the top of the page (northward).

Example: Based on what you have learned so far, what can you deduce from this simple weather diagram?

|

|

Mid latitude Cyclones

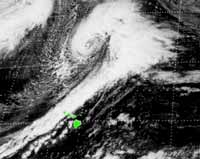

In virtually any satellite image of Earth, you will see huge cloud swirls in the midlatitudes with long tails stretching from their centers toward the tropics. These swirls (midlatitude cyclones) and their tails (cold fronts) are inextricably linked and part of the huge atmospheric turmoil unleashed each day in trying to balance the global heat budget.

To

a meteorologist, the word "cyclone" just means

"low pressure system," any low pressure system. The air around

the system is said to have "cyclonic

rotation," which is counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere.

Conversely, an anticyclone, or high pressure system,

has clockwise rotation in the northern hemisphere.

To

a meteorologist, the word "cyclone" just means

"low pressure system," any low pressure system. The air around

the system is said to have "cyclonic

rotation," which is counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere.

Conversely, an anticyclone, or high pressure system,

has clockwise rotation in the northern hemisphere.

Midlatitude cyclones, also called migratory lows, form and strengthen in the low pressure belts of higher latitudes discussed earlier (see Chapter 4 -> Global). They typically have central pressures of 990 to 1000 millibars and affect an area perhaps 1600 kilometers (1000 miles) in diameter.

As they grow, cyclonic motion strengthens around their centers, dragging cold Polar air from high latitudes equatorward, and warm Tropical air poleward. Thus they provide the engine for heat transfer from low to high latitudes. As the cold air moves equatorward into warmer air masses, it forms a cold front as shown in the diagram. Similarly, the warm air mass moves poleward creating a warm front. For the southern hemisphere, the pattern would be mirror image with the cold front stretching north of the low center, also toward the equator. The entire system of low pressure, cold and warm fronts, and attendant bad weather, moves from west to east with the westerly winds.

Midlatitude

cyclones can produce fast weather changes and cloudy, rainy weather.

The blue shading

in the diagram shows where most precipitation (rain

or snow) is likely to fall: along the fronts themselves, and in a circular

area around the center of the Low.

Midlatitude

cyclones can produce fast weather changes and cloudy, rainy weather.

The blue shading

in the diagram shows where most precipitation (rain

or snow) is likely to fall: along the fronts themselves, and in a circular

area around the center of the Low.

If you check the weather forecast for the continental USA, Europe, or East Asia, you will see that midlatitude cyclonic systems figure prominently in the analysis. They are easy to spot in the satellite imagery and produce predictable weather changes. They also affect Hawai'i as shown in the image. This is discussed in greater detail in the Hawai'i section of this chapter.