THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

Geography 101

ToC

WEATHER

Lifting

Air Mass

Fronts

Hurricane

Hawaii

Lifting

|

|

BOX 1 |

Although, clear skies are the atmosphere's simplest state, they seldom prevail. Clouds intrude and with them come rainfall and other weather elements.

Clouds and attendant precipitation form when air rises. Usually an initial upward push, called lifting, is required to start the process as discussed earlier under conditionally unstable air (see Chapter 5 -> Stability).

The four most common cloud starters are orographic lifting, convective motion, convergence and fronts. Where these forces occur, you will find Earth's wet places.

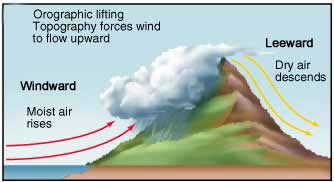

Orographic Lifting

Without mountains, the Hawaiian Islands would be sparsely vegetated and dry. But because air is forced to rise as wind blows onto the windward slopes of mountains, the Islands extract about 3 times as much rain from the air as falls on the open ocean. Hawaiian mountains collectively milk an additional 20 billion cubic meters of water from the atmosphere each year.

The

science is pretty straightforward, as shown in the diagram. Wind pressure

against

a mountain barrier forces air to rise on the mountain's windward side.

As it rises, it cools to the dew point, clouds form, and rain may fall.

On the

leeward side

of the

mountain,

the now-drier air heats quickly as it flows downward

producing hot, dry offshore winds and a low rain area called

a rainshadow. The driest place in Hawai'i at sea level,

Puako on the Big Island, lies in the rainshadow of the Kohala Mountains

and Mauna Kea.

The

science is pretty straightforward, as shown in the diagram. Wind pressure

against

a mountain barrier forces air to rise on the mountain's windward side.

As it rises, it cools to the dew point, clouds form, and rain may fall.

On the

leeward side

of the

mountain,

the now-drier air heats quickly as it flows downward

producing hot, dry offshore winds and a low rain area called

a rainshadow. The driest place in Hawai'i at sea level,

Puako on the Big Island, lies in the rainshadow of the Kohala Mountains

and Mauna Kea.

The amount of rainfall generated by orographic lifting depends largely on the depth of the cloud formed. This, in turn, depends on the shape and height of the mountain. Why, for example, does Kaua'i have the highest rainfall in the Islands, even though it does not have the highest mountain? The answer, once again, lies with the trade wind inversion. Mountains such as Wai'ale'ale and West Maui rise to just below the inversion level and thus the air can flow over the summit, adding depth to the cloud. For larger mountains, like Mauna Kea and Haleakala that rise well above the inversion, air must flow around them and thus clouds do not grow as deep.

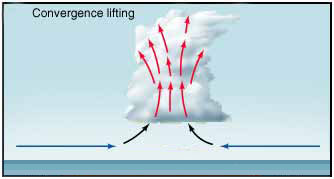

Convergence

Convergence

Remember the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)? It produces the equatorial rain that support Earth's tropical rainforests. The word convergence means, "to come together." Typically, this happens when air streams flow on convergent paths, either obliquely or directly toward each other. This is fairly common on islands or peninsulas, which heat during the day and draw onshore air from all directions in sea breezes.

Look at the Pacific Ocean image below showing the tropical trade winds in both the northern and southern hemispheres on a typical day. See how the flow lines converge in the center of the image near the equator? This convergence causes uplift to form the band of clouds that so clearly identifies the ITCZ on daily satellite images.

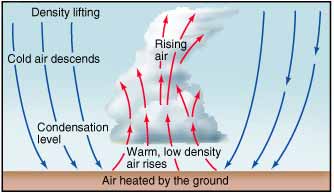

Convection

Convection

refers to air rising because it is buoyant,

meaning that it is warmer and less dense than the air around it. This

typically happens over a warm spot on the Earth's surface, such as a

bare soil field that heats during the day as shown in the diagram.

Convection

refers to air rising because it is buoyant,

meaning that it is warmer and less dense than the air around it. This

typically happens over a warm spot on the Earth's surface, such as a

bare soil field that heats during the day as shown in the diagram.

The diagram points out another feature of convection clouds, a return circulation. Notice how warm air rises in the cloud, then cooler air returns to the surface outside of the cloud. This sinking air produces the characteristic clear sky openings that separate cumulus clouds. Next time you look up and see puffy trade wind cumulus clouds, imagine the air inside the cloud rising and the air between the clouds sinking back toward the surface.

Daytime

heating during summer can produce deep convection clouds, complete with

torrential rainfall and thunder and lightning over

continental areas, such as the American Midwest and India. Over tropical oceans,

warm pools of water often spawn groups of convection clouds and thunderstorms

that can eventually organize into a tropical storm or even a hurricane.

Daytime

heating during summer can produce deep convection clouds, complete with

torrential rainfall and thunder and lightning over

continental areas, such as the American Midwest and India. Over tropical oceans,

warm pools of water often spawn groups of convection clouds and thunderstorms

that can eventually organize into a tropical storm or even a hurricane.

Fronts

Warm and cold fronts are particularly interesting and important lifting forces. Fronts mark the boundary of large air masses dragged into contact by midlatitude cyclones. We consider these phenomena in the next two sections, beginning with an explanation of air masses.