THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

Geography 101

ToC

WEATHER

Lifting

Air Mass

Fronts

Hurricane

Hawaii

Tropical Cyclones

|

The term "tropical cyclone" refers to any organized low pressure

system in the tropics. Meteorologists categorize these systems based on sustained

wind

speed (not gusts) according the following table:

|

|

|

BOX 1 |

In Hawaiian waters during the hurricane season, only a few tropical depressions strengthen to become tropical storms, and few of these grow into hurricanes. Although less feared than their more famous relative, tropical storms and tropical depressions can still cause significant damage. Winds may not be severe as hurricanes, but they can dump huge amounts of rainfall when they pass over land. Many of the thunderstorm and flooding events during the warm season in Hawai'i are caused by the passage of these systems.

Hurricanes

Any weather phenomenon that earns its own name must be fearsome indeed. A large hurricane can roil over a million cubic kilometers of atmosphere per second, generate 130 kph (80 mph) winds over a swath 160 kilometers (100 miles) wide, kick up 15 meter (50 foot) waves on the open ocean, and dump over a half meter (20 inches) of rain when it hits land. In this section we look at some of the physical conditions required for hurricane formation and movement, how those requirements tend to protect the Hawaiian Islands, and some of the effects experienced during a hurricane.

Formation and Growth

Hurricanes have demanding requirements for formation and growth, including warm water to provide energy, a favorable atmospheric profile, and an initial disturbance that starts a positive feedback loop to strengthen the storm.

Warm

water:

Evaporation from the ocean surface transfers the necessary heat into the storm

to sustain

it and the warmer the water, the greater the heat transfer through evaporation

(see Chapter 5 -> Evap). Generally,

hurricanes only form when the ocean surface temperature is at least 27° C (80° F),

although they may later move over cooler water. The ocean south of Hawai'i

is almost

always warm enough for hurricane formation.

Warm

water:

Evaporation from the ocean surface transfers the necessary heat into the storm

to sustain

it and the warmer the water, the greater the heat transfer through evaporation

(see Chapter 5 -> Evap). Generally,

hurricanes only form when the ocean surface temperature is at least 27° C (80° F),

although they may later move over cooler water. The ocean south of Hawai'i

is almost

always warm enough for hurricane formation.

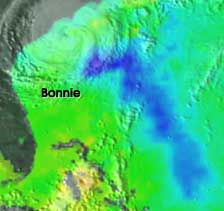

When hurricanes travel, they suck heat from the ocean surface, leaving a visibly cold trail. The image shows a cold water wake left by hurricane Bonnie in 1998 as it headed for the Atlantic Seaboard north of Florida. The blue area is 3 to 6° C (5 to 10° F) cooler than the surrounding ocean. The faint image of Bonnie in this microwave image can be seen in the upper left of this NASA image.

Wind Shear - Arrows show how wind speed and direction change with altitude. The length of the arrows indicates speed. Unfavorable conditions (b), (c), and (d) are all common over Hawaiian waters. |

Atmospheric Profile: Hurricanes are air creatures and the air available must possess qualities that nurture the storm. The atmosphere needs to be unstable and lack "shear," meaning that wind speed and direction must be the same at all altitudes. The necessary shear and stability configuration is shown in diagram (a) to the left. Generally, these conditions do not exist near the Hawaiian Islands and this helps account for the relative rarity of hurricanes. More commonly, the profile is stable (as shown in (b)) or has wind shear (illustrated in (c) and (d)). Shear, in particular, tends to protect Hawai'i from storms that have already formed and are moving toward the Islands. If the surface winds blow a different direction or speed than the upper level winds, the heat of the storm will dissipate, a condition meteorologists call "having its head cut off."

Initial disturbance: Hurricanes are intense low pressure systems that grow out of existing, weak, low pressure centers. In the Central Pacific Zone (Hawaiian waters area), the initial disturbance generally relates to the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), a low pressure band of calm winds and thunderstorms that girdles the equatorial Earth as discussed earlier (see Chapter 4 -> Global). When the ITCZ moves far enough north of the Equator, say 5 to 10° north, a group of thunderstorms may slowly merge into a coherent circular system. The ITCZ needs to be sufficiently far north because no Coriolis force exists at the Equator and thus a circular wind system cannot form. Hurricanes cannot exist at the equator or cross the equator for this reason.

The satellite image shows the genesis of Hurricane Iwa in 1982 southwest of Hawai'i. The image spans a latitude range from the Equator to about 25° north. The ITCZ is the wavy band of clouds crossing the Pacific north of the equator. Iwa grew out of an active area of the ITCZ at about 7° north (bright circle to the left) and traveled northeast to reach Hawai'i. Iwa's path was unusual, typically most hurricanes approach the Islands from the east.

Anatomy

Anatomy

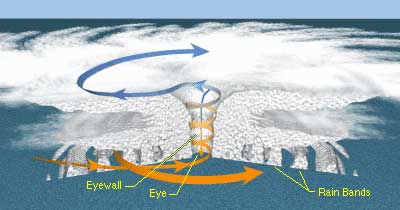

A hurricane is essentially a highly organized mass of severe thunderstorms with rain bands and strong winds circling a a calm central eye. Hurricane Iniki (1992) had a small, compact eye of about 30 kilometers (19 miles) across, while Hurricane Fernanda (1993) had an enormous eye of about 80 kilometers (50 miles) in diameter. In general, lower eye pressures create more powerful storms. During Iniki, for example, the surface air pressure dropped below 950 mb south of Kaua'i. The overall cloud coverage can span hundreds of kilometers. Cloud tops can rise to the tropopause, typically about 16 kilometers (10 miles) above the surface.

Look

carefully at the cloud movement in the animation of Iniki approaching Kaua'i.

The surface clouds (bright white) rotate counterclockwise as

air spirals inward toward the low pressure center of the storm. The upper level clouds,

the lighter clouds on the edges, move the OPPOSITE direction, clockwise,

as rising air vents outward at high altitudes and spirals away from the storm center.

In other words, hurricanes have low pressure at the surface beneath high pressure at high altitudes. You may want to review motion around pressure centers in Chapter

4 -> Motion.

Look

carefully at the cloud movement in the animation of Iniki approaching Kaua'i.

The surface clouds (bright white) rotate counterclockwise as

air spirals inward toward the low pressure center of the storm. The upper level clouds,

the lighter clouds on the edges, move the OPPOSITE direction, clockwise,

as rising air vents outward at high altitudes and spirals away from the storm center.

In other words, hurricanes have low pressure at the surface beneath high pressure at high altitudes. You may want to review motion around pressure centers in Chapter

4 -> Motion.

Damage and Hazard

Wind speeds are greatest at the eye wall and diminish with distance outward. Iniki, for example, had sustained winds of over 225 kph (140 mph) as it passed over Kaua'i. Damage can be caused by force of the wind itself or from flying debris. In the northern hemisphere, wind speeds are highest to the right of the direction of motion of the eye, as the storm's speed of rotation is added to the speed of movement over the surface.

Predicting wind direction The image shows historic hurricane tracks near the Islands with a storm shown on Dot's path for a wind direction reference. Imagine the storm following the Iniki track. For Kaua'i, what was the wind direction before the eye (the red LOW) reached the island? What was the wind direction after the eye passed to the north? Check your answers using the Iniki animation above. For hurricane Iwa, was Kaua'i in the highest or lowest wind speed side of the storm (reread the Wind paragraph above)? In 1871 a plantation manager in Kohala (yellow dot) reported that "tornado" force winds came first from the north, then from the west, then the south. What storm track would cause those wind changes over Kohala? Did the probable hurricane pass north or south of Kohala? |

|

Storm surge and overwash from large waves can also cause major damage. Iniki brought widespread flooding to the southern coast of Kaua'i, causing millions of dollars in structural damage. Because large swells travel away the storm system, they can damage areas that do not directly experience storm winds. Waves from Iwa caused flooding along O'ahu's leeward coast. Waves from Iniki washed out sea walls in Kailua-Kona on the Big Island. Waves from Estelle destroyed several homes along the Puna coast, even though the storm itself passed well south of the Big Island.

Rain and flooding are major hazards from all tropical cyclones, not just hurricanes. Often, the remnants of weakened tropical cyclones from the East Pacific will pass near or over the Islands. When this happens, the trade wind inversion weakens or is absent, and deep clouds with their accompanying thunderstorms and torrential rains may develop.

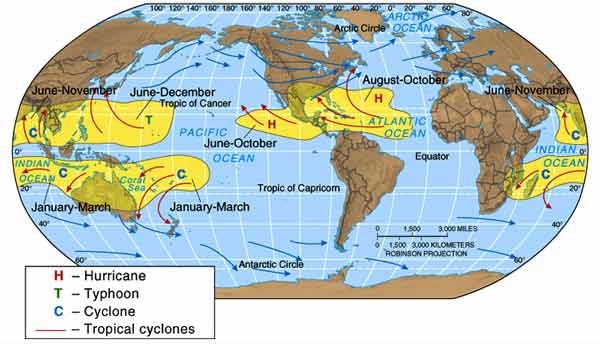

Global Hurricane Distribution

Hurricanes occur in tropical oceans under the favorable formation conditions described above. As you can see by the yellow areas on the distribution map below, most hurricanes occur on the western sides of tropical ocean basins. Here, water tends to be warmer and the atmosphere unstable. The West Pacific in the northern hemisphere has the distinction of experiencing not only the most hurricanes, but the most intense as well. For areas like the Philippines and Guam, annual "typhoons" are a way of life. Guam has been hit so many times that most of its buildings are made of concrete to withstand the inevitable howling wind and flying debris. The southwest Atlantic off the coast of South America is an anomaly to the global pattern experiencing virtually no hurricanes at all. The only hurricane ever recorded in the area hit the coast of Brazil in 2004.

The map also indicates local names for hurricanes in various parts of the world, with the most common being hurricane (west Atlantic, east Pacific), typhoon (northwest Pacific), and cyclone (Indian Ocean and southwest Pacific). Another term used in Australia is willy-willy and in the Philippines, bagyo.